Obituaries and Memorials to the Soldiers of Tregarth

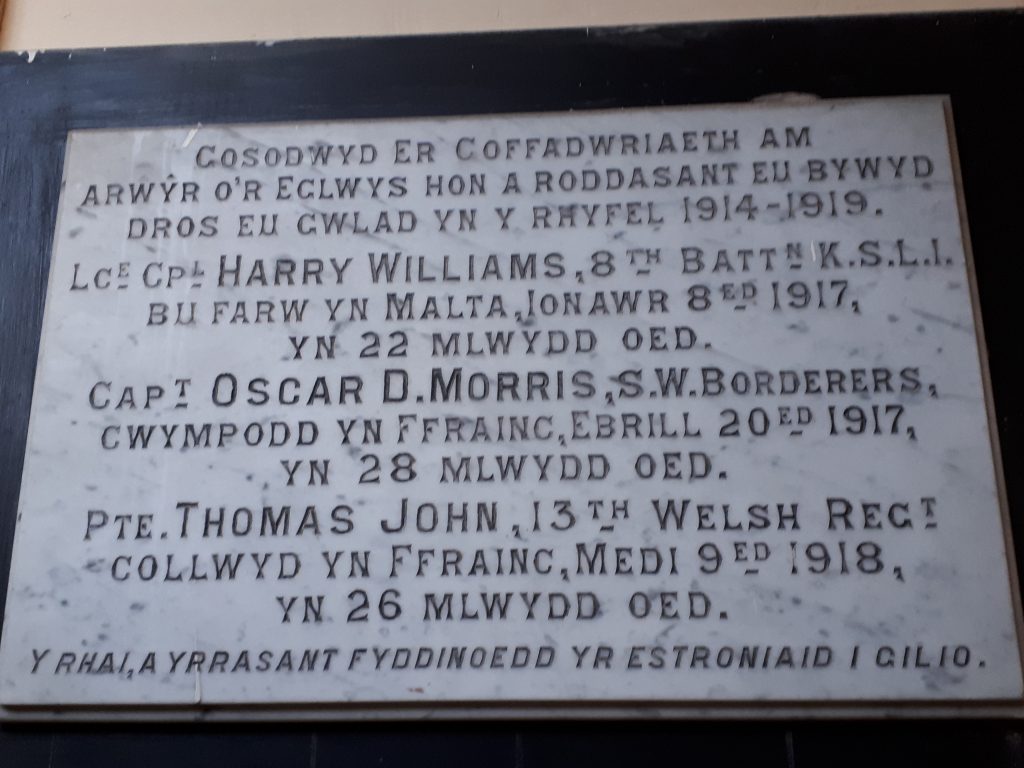

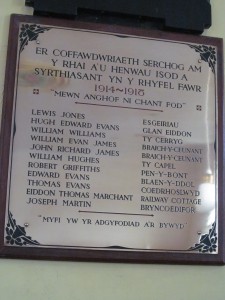

Tregarth is a village in the Ogwen Valley, Caernarfonshire. Its Wesleyan Methodist chapel, ‘Shiloh’ and church, ‘St Mary’s’ are still open and have memorials dedicated to those who lost their lives in the First

World War. The church also holds the Sunday school’s memorial and a stained glass window dedicated to the Brock brothers, whose father was the headmaster of the local school. The gates to the church are also a memorial to those from Tregarth who died during both world wars.

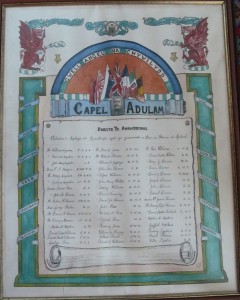

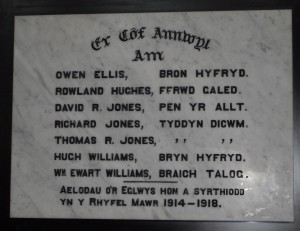

Shiloh’s memorial lists the names and homes of members of the congregation who died fighting the war (for example: Richard Jones – Tyddyn Dicwm). It was necessary to include the street or farm where the fallen had lived, as the community identified them by their place of residence rather than by their surname. Therefore, Richard Jones would probably have been known as Richard Tyddyn Dicwm. The gates outside St. Mary’s and the Sunday school memorial also note where the soldiers had lived in Tregarth. This was also important because a number of the soldiers had the same surname – there are 43 names on the Sunday school memorial, 13 of whom are ‘Jones.’

Shiloh’s memorial lists the names and homes of members of the congregation who died fighting the war (for example: Richard Jones – Tyddyn Dicwm). It was necessary to include the street or farm where the fallen had lived, as the community identified them by their place of residence rather than by their surname. Therefore, Richard Jones would probably have been known as Richard Tyddyn Dicwm. The gates outside St. Mary’s and the Sunday school memorial also note where the soldiers had lived in Tregarth. This was also important because a number of the soldiers had the same surname – there are 43 names on the Sunday school memorial, 13 of whom are ‘Jones.’

St. Mary’s memorial, by contrast, seems less concerned with remembering the soldiers as part of the local community, and more concerned with showing their important role in the Great War. The memorial does say where the soldiers lived. In the majority of cases it does not record the first names of the deceased. Instead, it lists their rank in the army; first initial; surname; area in which they fell and the year they died. The stained glass memorial to the Brock brothers in St. Mary’s echoes this focus on military accomplishments. Although we know from the Sunday school memorial that they lived at Sunnyside, the inscription on the stained glass makes no reference to this. It reads: ‘In loving memory of Lieut. Herbert Leslie Brock (BA Wales) 20th Div. MGC. Killed in action in France April 10th 1918 age 28, and Private Ivor James Baxter Brock 14th Batt. R. W. F. killed in France Sept. 1st 1917 age 19. “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.” S. John XV 13.

Different memorials commemorated men in different ways, and the same can be said of newspaper obituaries. This project seeks (among other things) to analyse memorials from all over Wales to see if it is possible to identify patterns in their styles and wording. For example, was including the soldier’s home address on a memorial a trait unique to north Wales, or was it common across rural Wales? Did all Anglican churches note where and on what date members of their congregation had been killed in action? Further research also needs to be done on whether the religious denomination or political outlook of the newspapers had an influence on the style of obituary they published.

Below are examples of Tregarth men’s obituaries from three newspapers. Y Llan was a bilingual Anglican newspaper, whilst Y Gwyliedydd Newydd was Wesleyan. Y Genedl was more political than religious. It supported the Liberal party, but welcomed contributions which reflected the socialist point of view.

Both Y Llan and Y Genedl’s obituaries seem to stress that the fallen were brave men who had fallen for king and

county. Whilst Y Llan (28/4/1916, p. 7) extended its deepest sympathy to David Williams’s whole family, especially his widow, his young children and his mother, they believed that ‘ond y mae cysur i’w gael wrth feddwl ei fod wedi marw wrth wneud ei ddyletswydd’ (but there is comfort to be had in the thought that he has died doing his duty). A month later, Y Genedl (23/5/1916, p. 8) was even more emphatic that the soldiers were dying for a just cause. It’s article was about a memorial service to Richard Price Jones, but in the middle of the article it refers to all soldiers involved in the war: ‘Da gweled yr ardalwyr yn gollwng dagrau hiraeth, ac o barch, ar ôl y bechgyn sydd yn rhoddi eu bywydau i lawr i gadw y gelynion rhag gwneud ein gwlad fel Belgium, Serbia a Pholand.’ (It is good to see the locals shedding tears of loss and of respect for the boys who have given their lives to prevent the enemy from making our country like Belgium, Serbia and Poland.’) Richard Price Jones’s memorial service was held at the Calvinistic Methodist chapel in Tregarth, but unfortunately I do not know if the chapel is still in use or if any memorials are preserved there.

By contrast, the obituaries in Y Gwyliedydd Newydd seemed less certain that the Great War was a just cause that was worth the cost. It also acknowledged that not all soldiers on the battlefield wanted to be there. My research so far has not been very extensive, so the first obituary I found relating to a soldier from Capel Shiloh is from September 1916. Conscription had been introduced in March 1916, and attitudes towards the war in Britain as a whole were less fervently patriotic than in the hopeful days of 1914. Also, as Dafydd Roberts has explained in his article, ‘”Dros ryddid a thros ymerodraeth” Ymatebion yn Nyffryn Ogwen 1914-1918’ (“For Freedom and for Empire: reaction in the Ogwen Valley 1914-1918,’ Caernarvon Historical Society Transactions, 1988-9 p. 107- 123), the residents of the Ogwen valley had been reluctant to enlist since the outbreak of war. Methodism in pre-1914 Wales had a strong pacifist tradition, which may also have influenced the newspaper’s views about the war. Y Gwyliedydd Newydd’s coverage of Rowland Hughes’s memorial service (12/9/16, p. 6) refers to the battlefield as ‘faes y gyflafan ofnadwy’ (the field of awful massacre). When Owen Ellis was killed at the front, the paper (30/1/1917, p. 7) played with the phrase ‘maes y gad’ (battlefield) calling it instead ‘maes y gwaed’ (field of blood). By the time David Richard Jones was killed (2/7/1918, article published 24/7/1918, p. 8), Y Gwyliedydd Newydd was referring to the whole war as ‘y gyflafan erchyll yma’ (this horrific massacre).

In two articles about members of Shiloh’s congregation who had died at the front, the paper makes it quite clear that they had not enlisted because they believed in the glory of war. The first, Rowland Hughes’s (12/9/16, p. 6), stated that he ‘Ymunodd a’r fyddin o argyhoeddiad dwfn. Methai a chysgu’r nos gan faint bwysai ar ei feddwl. Cychwynnodd i’r chwarel at ei waith, troes yn ei ôl, a cherddodd i Fangor i ymuno a’r fyddin, – “yr wyf i fod i listio, meddai, i ymladd dros gyfiawnder.” (He joined the army from deep conviction. He could not sleep at night because of the weight on his mind. He started towards his work at the quarry, turned around, and walked to Bangor to enlist in the army, – “I am going to enlist, to fight for justice”.) Although he had eventually decided to fight for his principles, the newspaper makes it clear that this was not an easy decision to make. The second example is Owen Ellis (30/10/17, p. 7). When describing his character, Y Gwyliedydd Newydd said he was: ‘un o’r bechgyn tyneraf ei ysbryd, a pharatoaf ei gymwynas. Er iddo farw’n filwr ar faes y gwaed, nid milwr mohono wrth anianawd. Yr oedd o duedd enciliedig, gwell ganddo wrando na llefaru. Er hynny, pan alwyd arno i gyflawni’r annymunol gwnaeth hynny yn ffyddlon a theyrngarol. Da gennym glywed gan ei Gaplan iddo farw fel y bu fyw, yn llawn arwriaeth.’ (He had one of the gentlest souls, and was always happy to help. Although he died a soldier on the field of blood, he was not a soldier at heart. He was of a retiring nature, preferring to listen than to preach. Despite this, when he was called upon to do the objectionable he did that faithfully and loyally. We are glad to hear from his Chaplain that he died as he lived, full of heroism.) Although this extract refers to Owen ‘doing his duty’ and ‘dying a hero’ it also, I think, makes it explicitly clear that he should not have died ‘on the field of blood.’

This article has only looked very briefly at the some of the memorials in one village. There is far more scope for others to find out more about the memorials and obituaries in their own local communities.

Meg Ryder April 11th, 2016

Posted In: chapels / capeli, memorials

Tags: Dyffryn Ogwen, Tregarth

The Monmouthshire Regiment and the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge by Shaun McGuire

It is possible that the total of 85 men from Newport killed on 8 May 1915 is the greatest loss suffered by any Welsh town in a single day in the First World War. They were part of the Battle of the Frezenberg Ridge, which was part of what has become known as the Second Battle of Ypres.

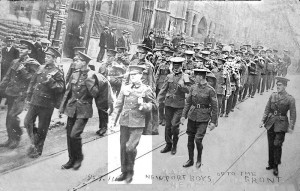

This photograph shows men marching down Stow Hill from the Drill Hall in the summer of 1914: the caption says ‘Newport boys off to the front’. The man highlighted at the front is Job William White, who was one of those killed on 8 May 1915. Further behind him is John Albert Pope, who was killed three years after the photograph was taken – on 17 June 1917. It was at the Drill Hall in Stow Hill, Newport that the First Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment recruited soldiers, and these men (along with the other two battalions in the regiment) became heavily involved in the second Battle of Ypres, which began on 22 April 1915.

This photograph shows men marching down Stow Hill from the Drill Hall in the summer of 1914: the caption says ‘Newport boys off to the front’. The man highlighted at the front is Job William White, who was one of those killed on 8 May 1915. Further behind him is John Albert Pope, who was killed three years after the photograph was taken – on 17 June 1917. It was at the Drill Hall in Stow Hill, Newport that the First Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment recruited soldiers, and these men (along with the other two battalions in the regiment) became heavily involved in the second Battle of Ypres, which began on 22 April 1915.

On 8 May the Monmouthshire Regiment were trying to defend the Frezenberg Ridge from a ferocious German attack. By the end of the day, the Regiment had lost 211 men and officers – 150 from the First Battalion, 19 from the Second and 42 from the Third. By the end of May the three battalions had lost a total of 515 men, with the Third Battalion suffering the greatest losses.

It was during this battle that Captain Harold Thorne Edwards replied to the German’s offer of surrender with the words, “Surrender be damned” and he and his men made the ultimate sacrifice. The scene of Captain Edwards and his men’s last stand is depicted in Fred Roe’s painting entitled “Surrender be damned” which was painted in 1935 after being commissioned by the South Wales Argus. It shows Captain Edwards firing his revolver at the advancing Germans. I believe the painting is now being displayed at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery after being hung in the foyer of Newport City council’s civic centre for many years.

battle that Captain Harold Thorne Edwards replied to the German’s offer of surrender with the words, “Surrender be damned” and he and his men made the ultimate sacrifice. The scene of Captain Edwards and his men’s last stand is depicted in Fred Roe’s painting entitled “Surrender be damned” which was painted in 1935 after being commissioned by the South Wales Argus. It shows Captain Edwards firing his revolver at the advancing Germans. I believe the painting is now being displayed at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery after being hung in the foyer of Newport City council’s civic centre for many years.

During research for the Newport’s War Dead website I came across a photograph in the South Wales Argus, 9th May 1947, of Alderman Mrs. Sarah J Haywood dedicating a plaque in front of members of the Old Comrades Association of the Monmouthshire Regiment in Bellevue Park, Newport. This may have been a plaque to replace an original one which would have been attached to a grove of eight may trees (hawthorns) that were planted in the 1920s as a memorial to those of the Monmouthshire Regiment that died on the 8th May 1915.

My inquiries about this memorial established that the trees had now either died off or were cut down. Unfortunately this meant that an event that caused great sorrow and sadness to the family and friends of these Newport men was now no longer commemorated.

I then started a campaign to get a new memorial to commemorate the battle of Frezenberg Ridge and the men who died on the 8th May 1915. My campaign was taken up by councillor Charles Ferris and numerous other friends including my daughter, Shelley. Finances were raised and on the 8th May 2015 a new memorial was dedicated on the banks of the river Usk opposite the Blaina Wharf pub in Newport. The event was attended by many dignitaries and military personnel.

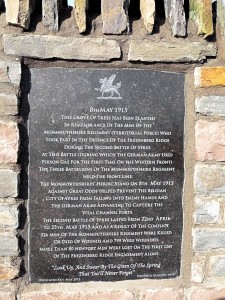

Inscription on the Memorial on Usk bank

8th May 1915

THIS GROVE OF TREES HAS BEEN PLANTED/ IN REMEMBERANCE OF THE MEN OF THE/ MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT (TERRITORIAL FORCE) WHO/ TOOK PART IN THE DEFENCE OF THE FREZENBERG RIDGE/ DURING THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES./

AT THIS BATTLE (DURING WHICH THE GERMAN ARMY USED/ POISON GAS FOR THE FIRST TIME ON THE WESTERN FRONT)/ THE THREE BATTALIONS OF THE MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT HELD THE FRONT LINE./ THE MONMOUTHSHIRES’ HEROIC STAND ON 8TH MAY 1915/ AGAINST GREAT ODDS HELPED PREVENT THE BELGIAN/ CITY OF YPRES FROM FALLING INTO ENEMY HANDS AND/ THE GERMANY ARMY ADVANCING TO CAPTURE THE VITAL CHANNEL PORTS./

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES LASTED FROM 22ND APRIL/ TO 25TH MAY 1915 AND AS A RESULT OF THE CONFLICT/ 526 MEN OF THE MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT WERE KILLED/ OR DIED OF WOUNDS AND 799 WERE WOUNDED./ MORE THAN 80 NEWPORT MEN WERE LOST ON THE FIRST DAY/ OF THE FREZENBERG RIDGE ENGAGEMENT ALONE./

Look Up, And Swear By The Green Of The Spring/ That You’ll Never Forget” – SIGFRIED SASSOON, 1919

Earlier on the same day, a new wooden sculpture was unveiled at the old drill hall on Stow Hill, where these men had been recruited. It depicts the scene from Fred Roe’s painting of Captain Harold Thorne Edwards and his men’s stance against the oncoming German attack.

Meg Ryder April 4th, 2016

Posted In: memorials

Tags: Monmouthshire Regiment/ Catrawd Sir Fynwy, Newport/Casnewydd

WW1 Memorial in Y Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel in Cardiff

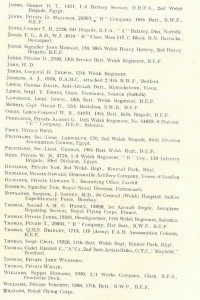

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

The memorial itself is impressive, being carved in marble.

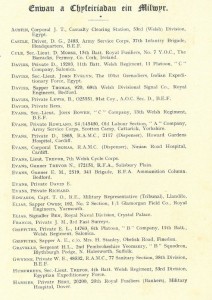

There are no records to indicate whether the chapel displayed a ‘Roll of Honour’ as the war was being fought, to highlight the contribution of a large number of the congregation to the war effort. However, the chapel’s Annual Reports do note the names of all the men who enlisted, and so we can trace how the war had a deeper effect every year on the congregation. There were 45 names on the list at the end of 1915, 62 by the end of 1916 and 66 in 1917 (including four who had been killed). The membership of the Tabernacl during the war fluctuated from around 520 to 560, so the total of 66 represents a sizeable proportion of the young male membership of the church.

List of chapel members serving in 1916

We can also see how the War’s impact became deeper and more painful from the minister’s comments in the reports. At the end of 1914 there was more discussion about the fire that had damaged the chapel than about the War, but the Rev Charles Davies’ comments became ever more emotional as the war dragged on and took an ever-increasing number of young men from his flock. Looking back upon 1916, he wrote that the young men left a large gap, and that their valuable contribution to the life of the chapel was deeply missed by those who were left. However, there is no doubt that the minister considered the war to be just, as he used such words as ‘teyrngarwch’ (loyalty), ‘dewrder’ (courage) and ‘aberth’ (sacrifice) to describe the men’s contribution to the war effort. He declared that as they faced the dangers and discomforts of the war, they were fighting ‘er amddiffyn ein gwlad, a sicrhau buddugoliaeth i gyfiawnder a gwir rhyddid yn ein byd’ (to defend our country, and to ensure a victory for justice and for the true freedom of our world).

In the lists of the men there is information about where a number of them were serving. At the end of 1916 a large number were in training camps in England or Wales; 14 with the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) on the Western Front; six in Egypt; four in Salonica and one in Bombay.

The first name on the memorial is Oscar D. Morris. It is possible to find a great deal of information about him: the letter he wrote as he sought to join the Welsh Army Corps are available on the Cymru1914 website – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/archive/4089505

One can also find a report on his promotion to lieutenant (August 1915 – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886208/7/ART121) and then reports on his death on the Western Front on 21 April 1917 (http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886989/1/ART11 and http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886999/3/ART35 ).

Oscar’s name is also to be found on the memorial in his home chapel – Salem Nantyffyllon.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

Reggie I.V.C.Thomas is the next name: he died on 24 November 1917 aged 19, while serving on the Western Front with the South Wales Borderers. He has no known grave, but his name is on the Cambrai memorial.

One can find John Wynford Thomas as a 12 year old boy in the 1911 Census, living in Lampeter Velfrey. There is no indication of when he moved to Cardiff, but he enlisted in the city, joining the South Wales Borderers. He was killed in Flanders on 31 October 1917.

Despite his common name, it is certain that the William John Thomas named on the memorial was an 18 year old who died on 11 July 1918 while serving with the Army Service Corps. He is buried in Cathays Cemetery, Cardiff.

However, the final name on the memorial is not on the list of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. According to the Tabernacl’s records he was a soldier in 1916, serving as a Gunner with the RFA (Royal Field Artillery) on Salisbury Plain. The chapel’s report says that he died on 18 February 1919.

g.h.matthews March 22nd, 2016

Posted In: chapels / capeli, memorials, Uncategorized

Tags: chapels / capeli, memorials, WW1

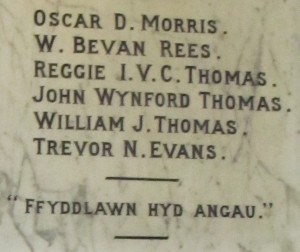

Castle Steel Works, Rogerstone, War memorial

Numerous companies erected memorials to their employees who were killed in the First World War and Welsh companies, works, railways and other industrial employers are well represented in the range of known and surviving memorials.

One of the larger Welsh industrial employers of the opening decades of the twentieth century was Guest, Keen & Nettlefolds Ltd, which owned steelworks, engineering works and collieries located mainly in south east Wales. The company had been created in 1902 by the amalgamation of earlier companies, amongst them Nettlefolds Ltd, whose Birmingham factories dominated UK production of wood screws. The steel that formed Nettlefolds’ raw material was made in the company’s Castle Steelworks at Rogerstone, a short distance north west of Newport.

Castle Steel Works had opened in 1888 as the successor to an earlier iron works of the same name at Hadley near Wellington in  Shropshire when Nettlefolds converted from using wrought iron to using steel as the raw material for wood screw manufacture. Many of the workmen from the original Castle Works migrated to work in the new Castle Works, followed by their families. The ‘Shroppies’ secured many of the skilled jobs and formed a distinctive community within the Rogerstone area.

Shropshire when Nettlefolds converted from using wrought iron to using steel as the raw material for wood screw manufacture. Many of the workmen from the original Castle Works migrated to work in the new Castle Works, followed by their families. The ‘Shroppies’ secured many of the skilled jobs and formed a distinctive community within the Rogerstone area.

Photograph of the Castle Steel Works in 1902

Lloyd George, Minister of Munitions in the early part of the First World War, famously declared that Britain was ‘fighting a steel war’, so crucial was the availability of steel supplies to the war effort. From November 1915 most UK steelworks came under Government control, including Castle Works. In the early part of the war many steelworks reported labour shortages resulting from enthusiastic rates of volunteering. After the industry came under Government control, skilled men were mostly prevented from volunteering; after conscription began in 1916 unskilled men in essential industries, including steel, were increasingly ‘combed-out’ and conscripted.

The Castle Steel Works memorial plaque lists many distinctively non-Welsh surnames and it is likely that descendants of the ‘Shroppies’ are well represented although it should also be recalled that the industrial areas of Monmouthshire experienced much emigration from Herefordshire and adjoining counties in the late nineteenth century and in the opening years of the twentieth century so not all the ‘English’ surnames necessarily originated in Shropshire.

The Castle Steel Works memorial plaque lists many distinctively non-Welsh surnames and it is likely that descendants of the ‘Shroppies’ are well represented although it should also be recalled that the industrial areas of Monmouthshire experienced much emigration from Herefordshire and adjoining counties in the late nineteenth century and in the opening years of the twentieth century so not all the ‘English’ surnames necessarily originated in Shropshire.

GKN commissioned similar bronze plaques for its other works, mines and factories. Whilst the wording (“In ever grateful recognition of the splendid patriotism and heroic self sacrifice of the following employees of Guest, Keen & Nettlefolds, Ltd.”, followed by the name of works) was consistent across all known plaques, the design of each plaque varied, especially with regard to the forms of the ornate borders and the arrangement of the fields in which the text (often divided in two), years, and lists of names were placed. There appears to have been a distinct policy of subtle variation within a broadly uniform ‘company design’. All the deceased are listed in alphabetical order by surname and forenames represented by initials.

The plaque is not inscribed with the name of the foundry that cast it. GKN possessed a number of foundries capable of producing this quality of casting and it is possible that the plaques were designed and cast in-house. It is at  least equally likely that the plaques were commissioned from a specialist external foundry.

least equally likely that the plaques were commissioned from a specialist external foundry.

Comparison with GKN’s other sites suggests that the Castle Works plaque was probably placed in the steel works general offices. When the Rogerstone works was replaced by the third Castle Works in 1938, located in Cardiff, the plaque moved along with many of the employees. After the Cardiff works came under new ownership in 1981, the Castle Works general offices at Cardiff were demolished and the plaque was earmarked for scrap. It was saved by a private individual however and in 2015 was donated to Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales jointly by the individual and the successor company that owns Castle Works Cardiff.

Robert Protheroe Jones

Principal Curator – Industry

Department of History & Archaeology

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Photographs of the memorial before and after conservation. Thanks to Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales for the images

g.h.matthews March 14th, 2016

Posted In: memorials, workplaces / gweithleoedd

situated on the wall behind the pulpit, so that any worshipper who is looking at the minister will have the memorial in their line-of-sight.

situated on the wall behind the pulpit, so that any worshipper who is looking at the minister will have the memorial in their line-of-sight. Esgeiriau

Esgeiriau