Mapping Welsh Memorials to the Great War

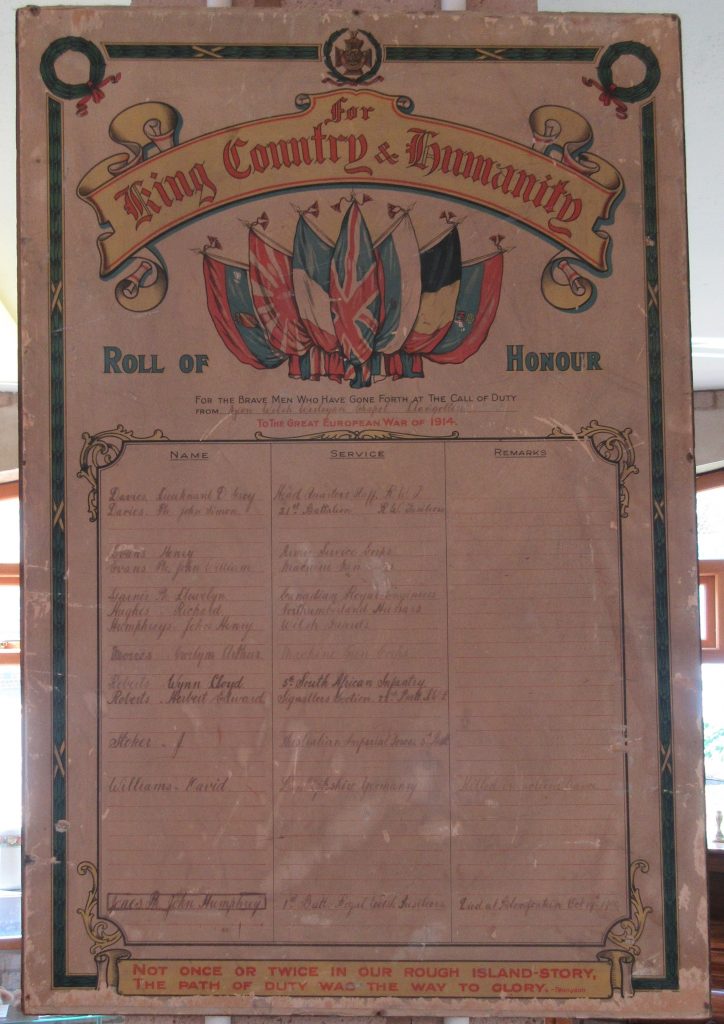

A new resource has been developed which illustrates some of the material gathered on the First World War memorials and rolls of honour in Wales.

Funded by the Living Legacies 1914-18 Engagement Centre, the Centre for Data Digitisation and Analysis at Queen’s University Belfast has worked with the information gathered by the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project, and also the Powys War Memorials Project, to create a map showing where these memorials are to be found. (The black dots are from the Powys project: the others are from ‘Welsh Memorials’).

Most of the memorials considered here were displayed in chapels, but there are also examples from churches, schools, clubs and workplaces.

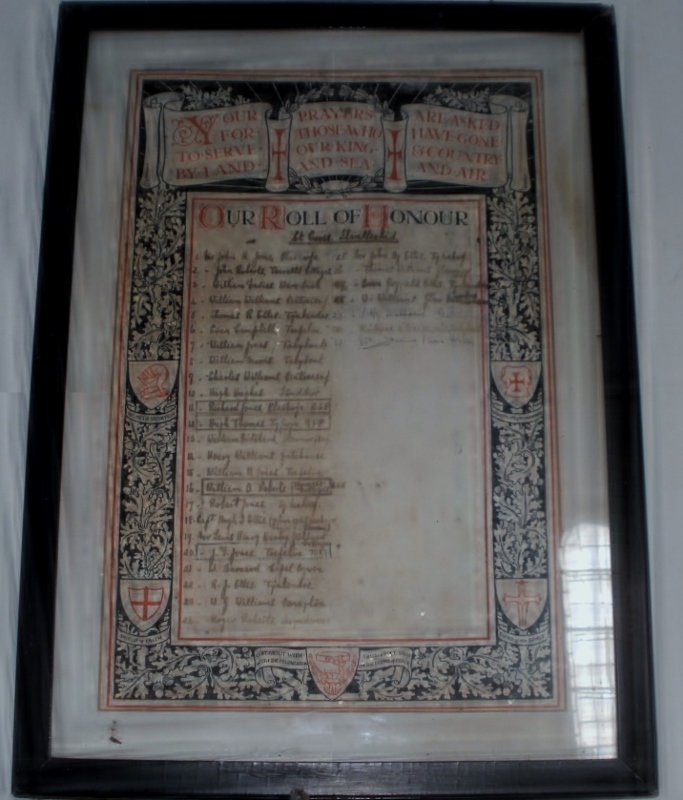

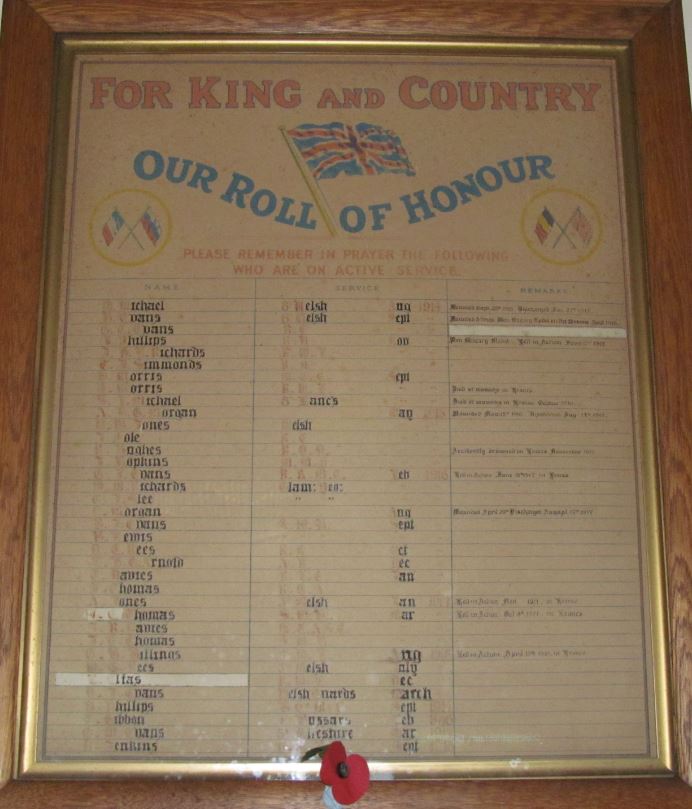

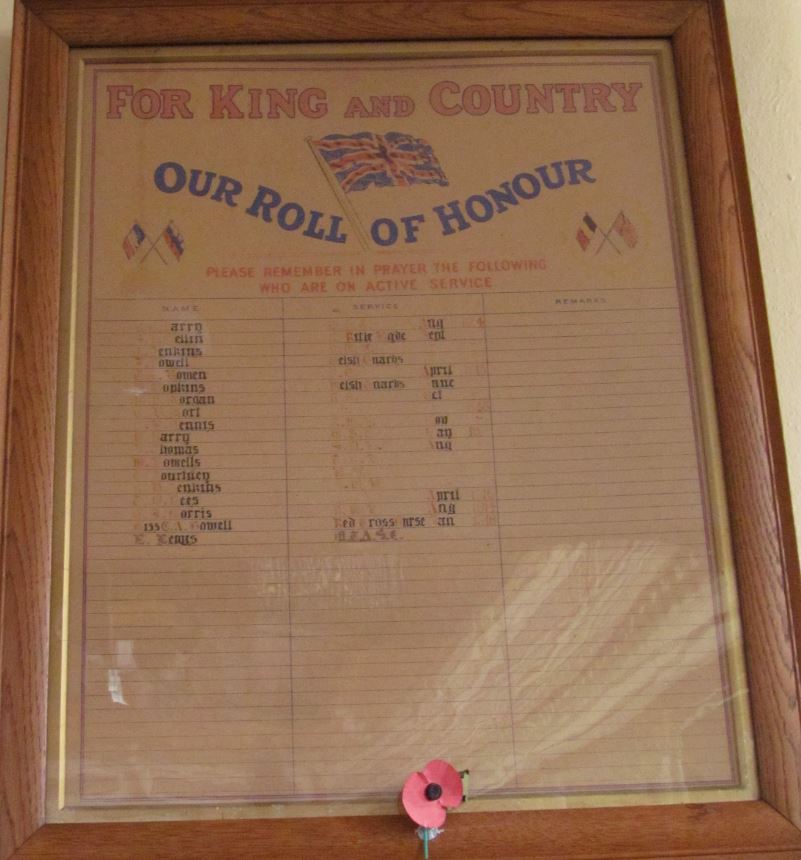

These objects of commemoration can tell us a lot about how individual communities were affected by the war, and how they chose to remember the events of 1914 – 1919, and those whom they lost on the battlefield. They vary greatly in their design, in their choice of words to describe those who are commemorated, in the information they contain, and in how inclusive they were in their choice of men and women to remember and honour.

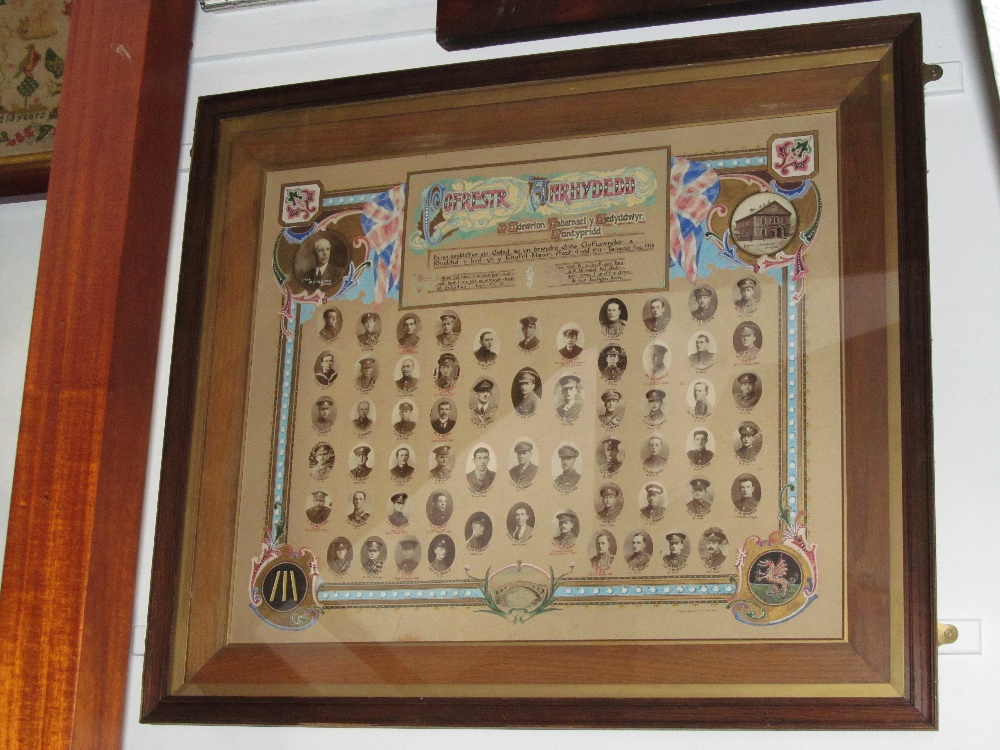

Whilst some rolls of honour feature very militaristic imagery, some memorials appear far more ambivalent about the necessity of war. One obvious example of these two contrasting perspectives can be found by comparing the choice of verse in the Tabernacle at Pontypridd (left), and Bethel Chapel in Llangyfelach, Swansea (right).

The Tabernacle in Pontypridd extolls the virtues of dying for one’s country – the poem is from the perspective of a mother who tells her son that “Dy fam wyf fi, a gwell gan fam, It golli’th waed fel dwfr, Neu agor drws i gorff y dewr, Na derbyn bachgen llwfr.” (“I am your mother, and a mother would rather you spilt your blood like a flood, or to open the door to the body of the brave, than accept a cowardly boy”). Bethel Chapel in Llangyfelach, on the other hand, quotes from the eulogy to Hedd Wyn (a Welsh poet who died at Passchendaele) by R. Williams Parry – “Garw rhoi’u pridd i’r briddell, mwyaf garw marw ’mhell” (It is grievous to give their remains to the earth, and harder still because they are far away).

There is also a wide range in regards to what the communities decided to record about those who were serving with the armed forces. Some, as in the Tabernacle (see above) included photographs. Others only recorded initials and surnames. Whilst some memorials and rolls of honour stated where the soldiers and sailors lived, others chose to list their ranks and regiments, or the date and place where they fell.

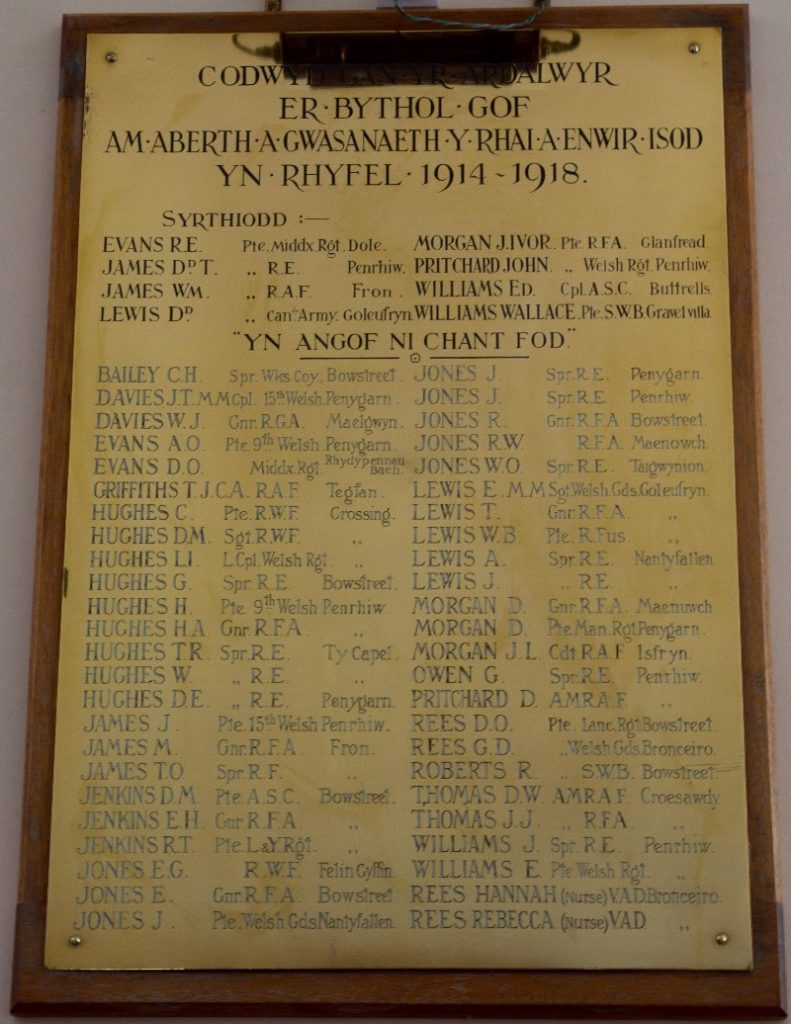

The map shows which areas chose to commemorate women who participated in the war effort. It seems that roughly a third of the chapel memorials in Wales include the names of women who served as well as men. Some of these are in clusters – such as those in the Pontypool area. This map resource makes it easy to identify these clusters. Very often the women’s names were separated out from the men’s as is the case in Capel-y- Garn, Bow Street, near Aberystwyth.

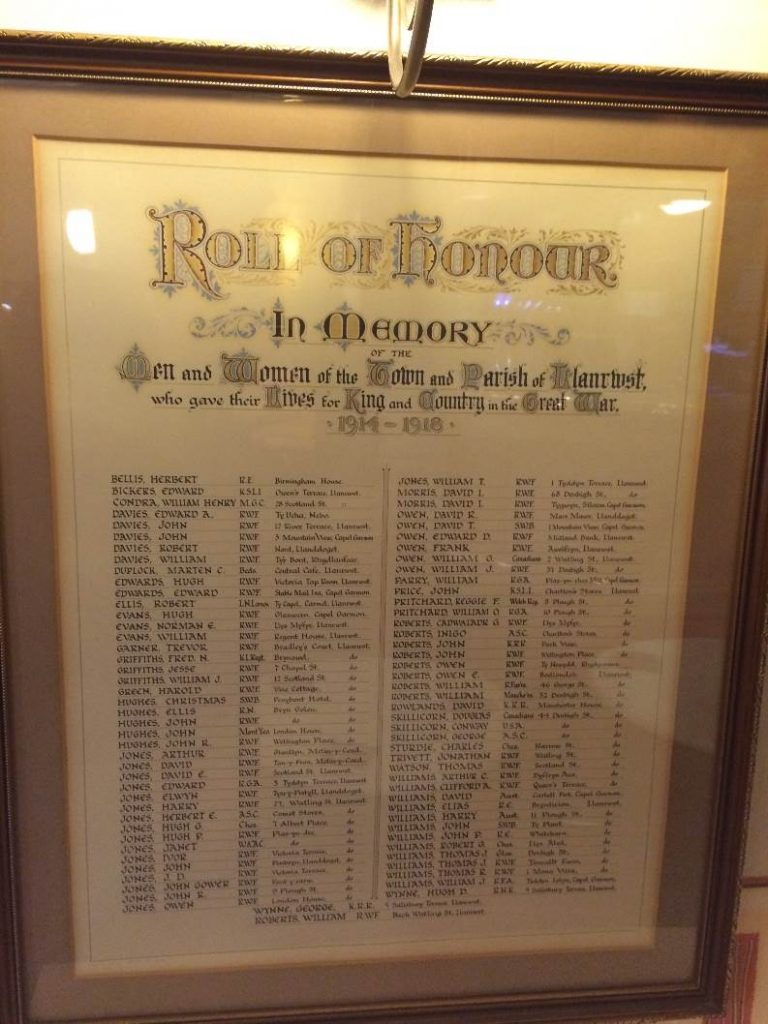

Sisters Hannah and Rebecca Rees are both listed as nurses on the right-hand bottom corner of the list. Occasionally women were listed among the fallen, as was the case with Janet Jones from Llanrwst, who was a Quarter Mistress with the Women’s Royal Air Force. On the roll of honour at the British Legion in Llanrwst, she is listed among the fallen men, in alphabetical order.

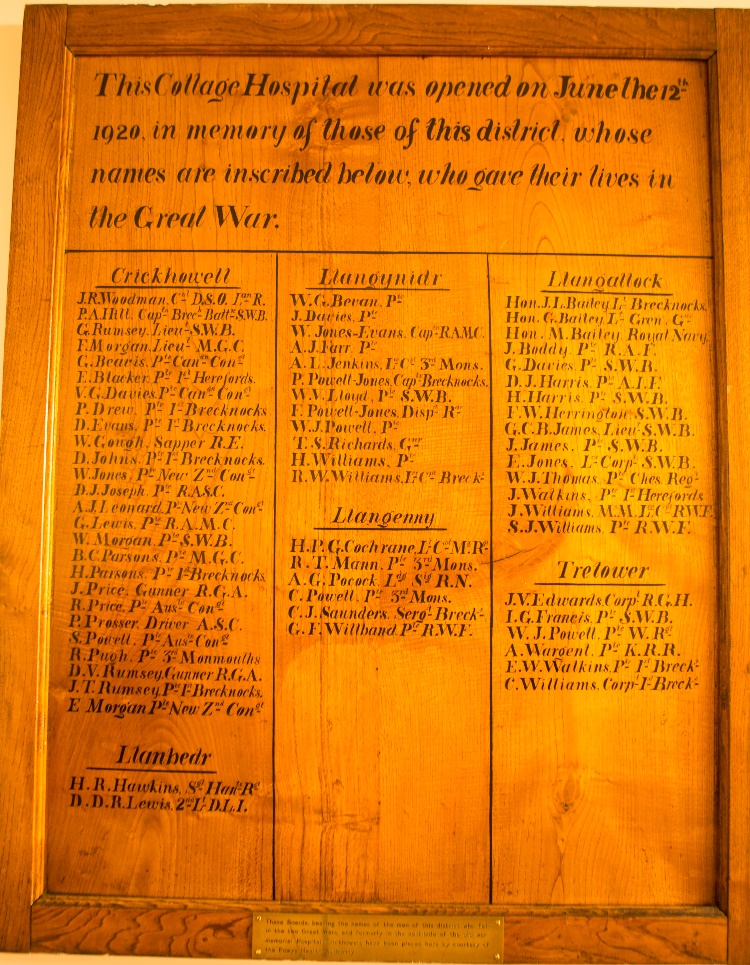

Another feature of this map is that it highlights which memorials and rolls of honour commemorate those men who served with overseas forces. Most men served with either the Canadian or Australian forces, although smaller numbers served with the Ghurkhas, New Zealanders and South Africans. The memorial which records the greatest number of men who fell whilst fighting with overseas forces is that of Crickhowell War Memorial Hospital. Out of a total of 67 men who fell whilst fighting in the First World War, 8 of them did so whilst serving with overseas forces (two Canadians, three New Zealanders and three Australians). Capel Seion in Llangollen also has a high proportion of men who served with overseas forces – 3 out of 12, that is, a quarter of those who served. One fought with the Australian Forces, another with the Canadians and the third with the South African Army.

Both Crickhowell and Llangollen are fairly rural areas of Wales, and perhaps the map of those who served with overseas forces can tell us something about the patterns of migration from Wales at the turn of the twentieth century. It also tells us how those who did emigrate maintained their links with the old country. One of those from Llangollen had emigrated to Canada a decade before the outbreak of war, but he was still considered enough of a Llangollen boy to be recorded on their Roll of Honour.

The memorial at High Street Baptist chapel, Abersychan, brings together many of the themes highlighted in this resource. The Roll of Honour has the dedication ‘To those who came to the help of the Lord against the mighty in the Great Struggle for the preservation of the sacred ideals of civilization’, showing that at the time of the memorial’s commission there was no question of who was in the right in the war. Eight men who died are listed, along with 70 men and 7 women who served. One of the men was with the Australian forces, and one with the Canadian Field Ambulance.

So far the Welsh Memorial Project has recorded over 160 memorials and almost a hundred rolls of honour from across Wales. These objects range from rough drafts of rolls of honour, such as this roll of honour from St Cross Church in Llanllechid, near Bangor, to statues such as this one from the Tabernacle in Aberystwyth, which was designed by the renowned Italian sculptor Mario Rutelli. This online map resource highlights the different ways of commemorating those who served from across Wales. It shows where rolls of honour were made, and those areas where memorials alone were more common. It gives a snapshot of the patterns of migration at the turn of the century, and it shows which communities decided that the contribution of local women to the war effort was worth commemorating.

g.h.matthews February 21st, 2018

Posted In: Uncategorized

Images of WW1 memorials in Welsh chapels

Here are images of some of the First World War memorials in Welsh chapels referred to in the book chapter:

Gethin Matthews, ‘Angels, Tanks and Minerva: Reading the memorials to the Great War in Welsh chapels’ in Martin Kerby, Margaret Baguley and Janet McDonald (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Artistic and Cultural Responses to war.

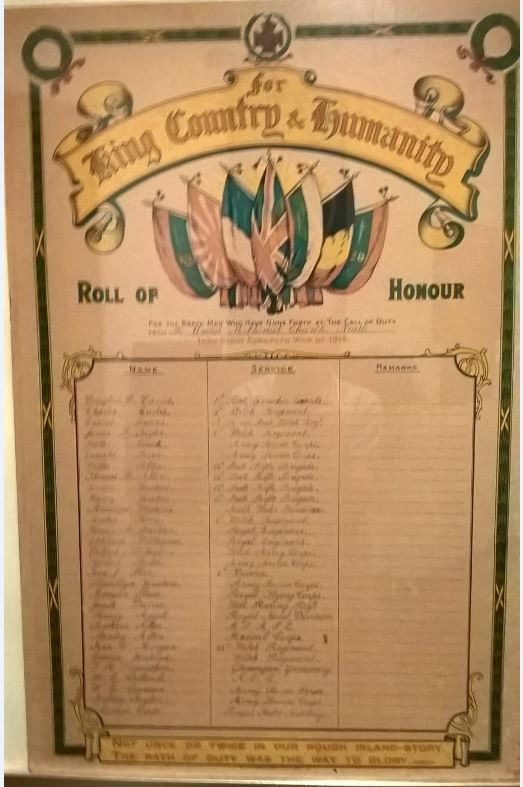

King’s Cross (Independent), London:

Maes-yr-Haf (Independent), Neath:

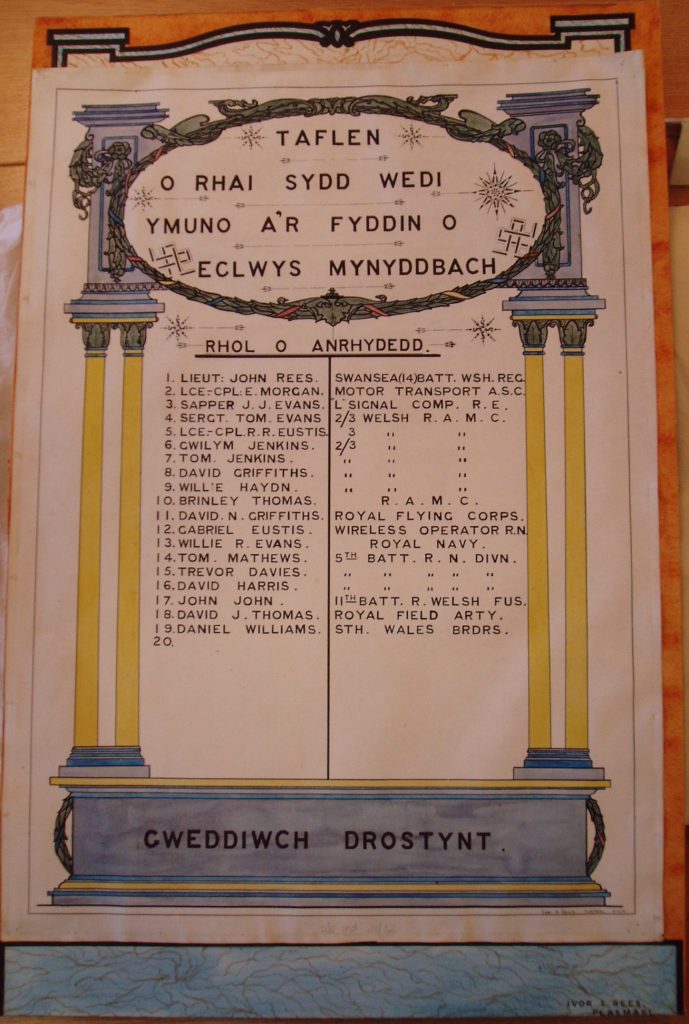

Mynyddbach (Independent), north Swansea – ‘Roll of Honour’ created in February 1916:

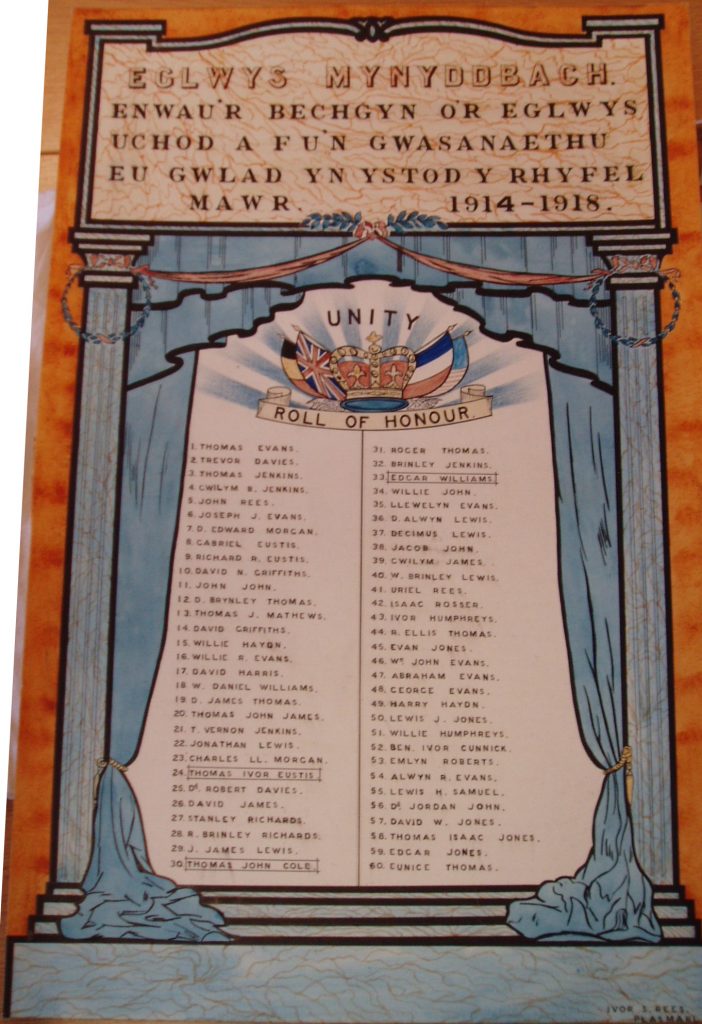

Mynyddbach (Independent), north Swansea – ‘Roll of Honour’ from 1921:

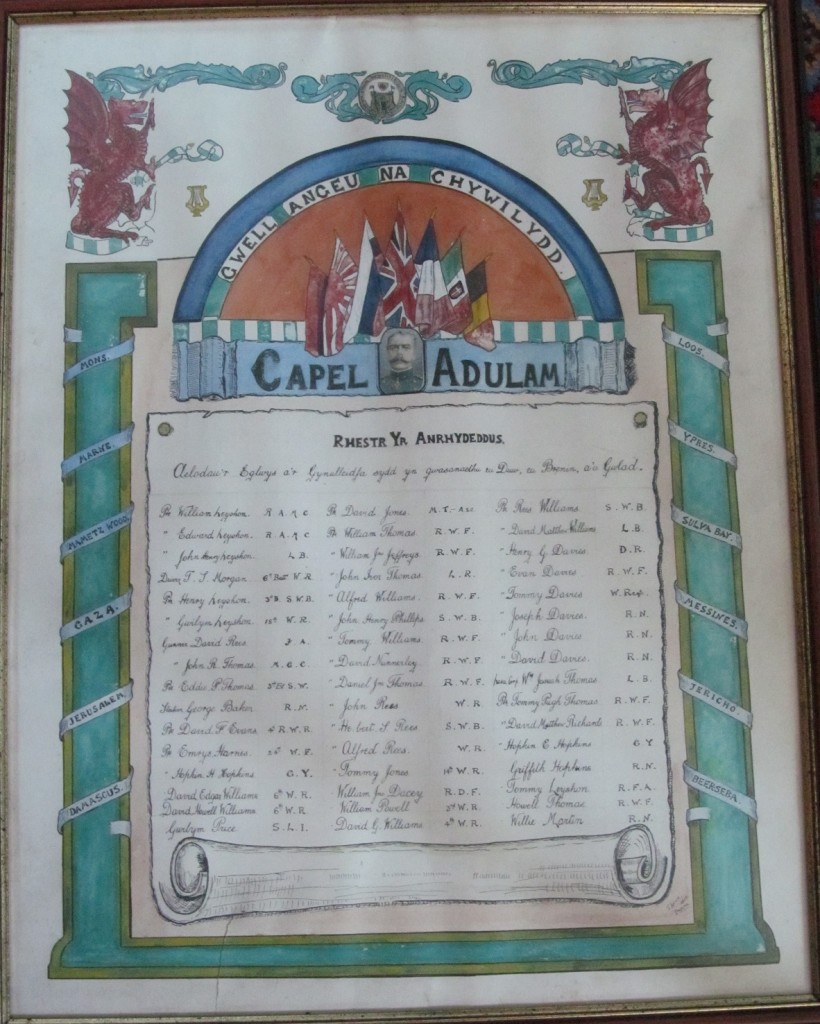

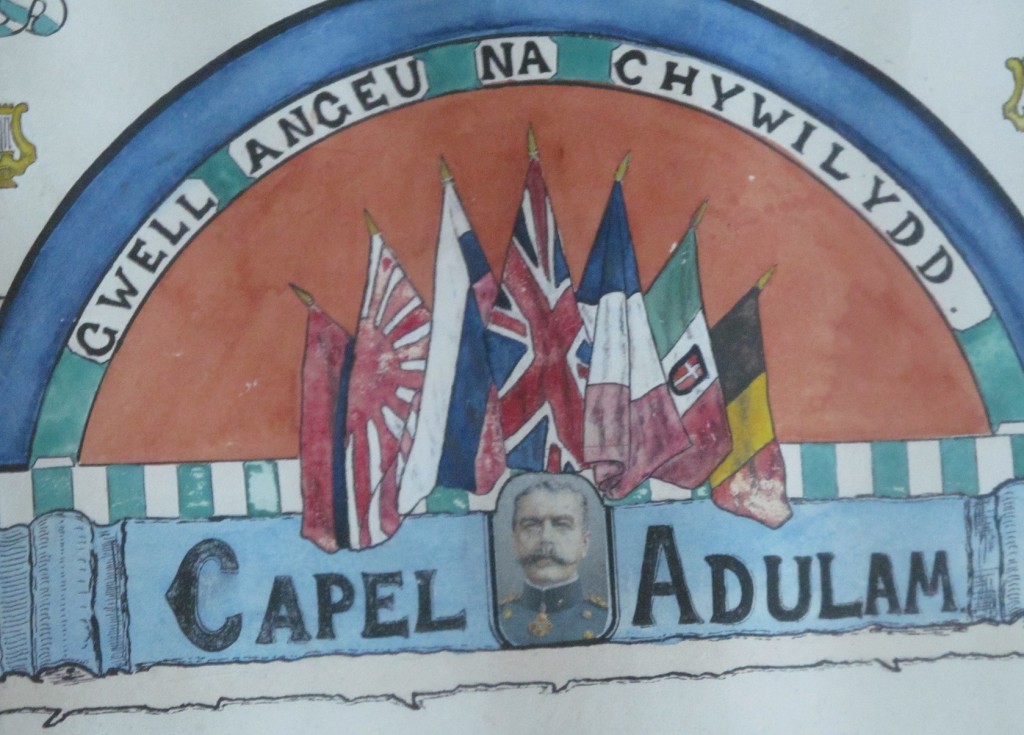

Adulam (Baptist), Bonymaen, north Swansea:

g.h.matthews February 7th, 2018

Posted In: Uncategorized

WW1 memorials in Morriston’s chapels

As the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project has gathered information about WW1 memorials from all over Wales, it has become clear that different parts of Wales can have different patterns of memorialisation. One clear generalisation is that industrial Wales had a greater number and variety of WW1 memorials than rural Wales. Although there are plenty of interesting exceptions, as a rule the WW1 memorials in rural Wales are thinner on the ground and have fewer names commemorated on them – which is obviously related to the sparser population in these areas.

Within industrial or urban Wales, there are also some interesting patterns: some areas where memorialisation was more intense than others. (Of course, one factor to bear in mind is the survival rate of memorials may not be uniform, and there are some parts of Wales where it appears that more have been lost than have survived). This article will focus in on Morriston, north Swansea, an area which had a very strong concentration of Nonconformist chapels in 1914.

The map above gives an idea of the distribution of these chapels (using the data of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales). Some of these chapels have closed down, while others have merged, but a fair number of their memorials are still extant.

The map above gives an idea of the distribution of these chapels (using the data of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales). Some of these chapels have closed down, while others have merged, but a fair number of their memorials are still extant.

As a result of there being so many chapels in one locality, there was an element of rivalry between them, and we can see that expressed during the period 1914-18 in terms of the question of how many recruits had joined from each congregation. Each institution sought to show that it was ‘doing its bit’ for the war effort, and so publicised the number of their young men who had joined the Armed Forces. For example, a newspaper report in 1916 declared that ‘Carmel Church is not one of the largest in Morriston, but has the good record of having 36 of its members and adherents with the Colours’ (Herald of Wales, 22 January 1916, p.8).

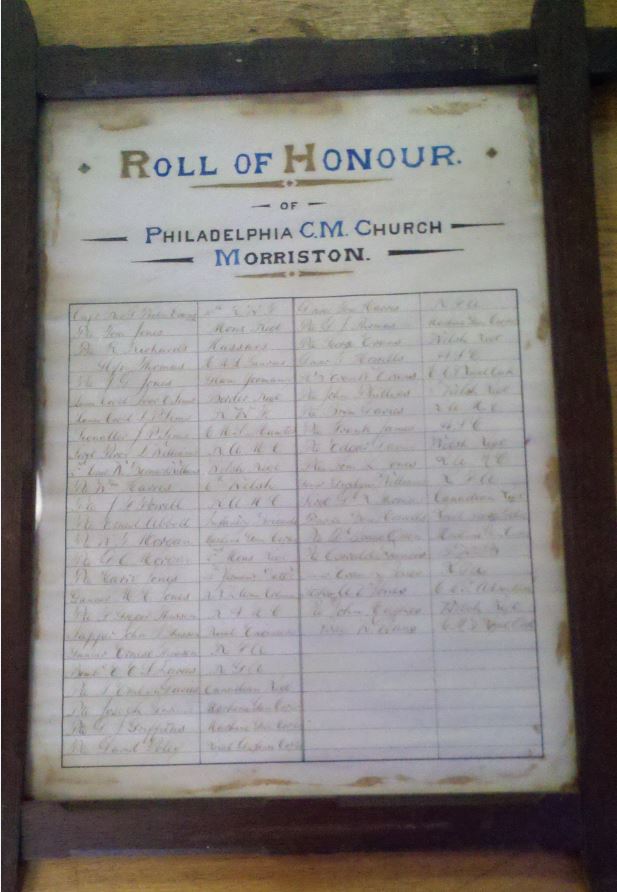

Here is an example of a contemporary Roll of Honour that was kept by Philadephia (Calvinistic Methodist) chapel, Morriston. It is likely that most local chapels had Rolls of Honour similar to this one on display as the war was being fought.

However, most of these have not survived, as they were superseded by more ornate memorials commissioned at the end of the war.

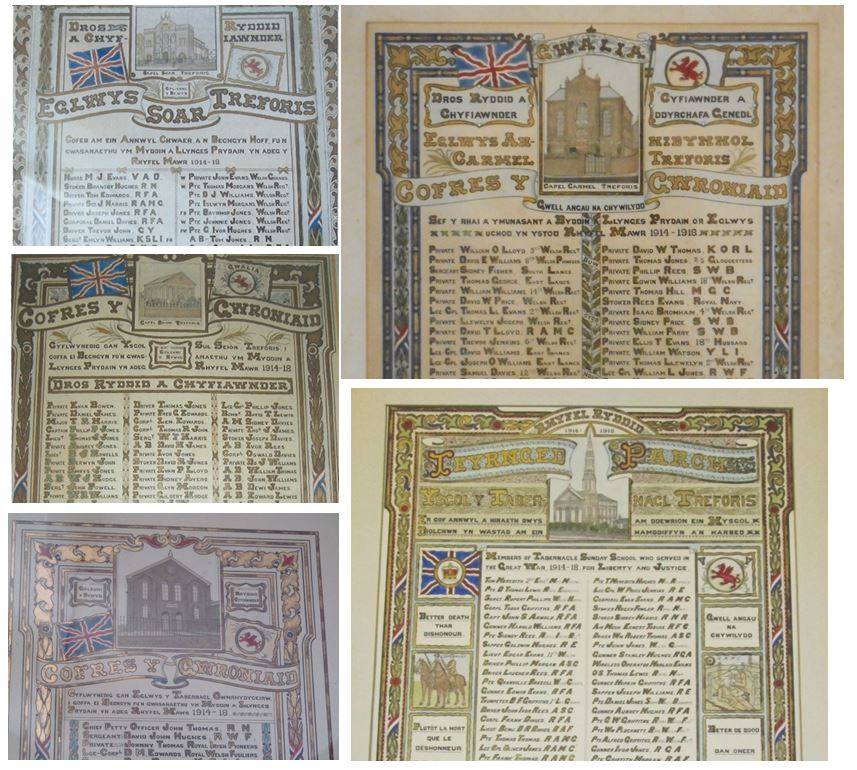

One thing that is clear from looking at the memorials below is that one local artist designed a number of them. W.J.James, of Penrhiwforgan, Morriston, designed all of the ones below: clockwise from the top-left – Soar; Carmel; Tabernacl; Tabernacl, Cwmrhydyceirw and Seion. In each of these designs there is an image of the chapel building in the middle towards the top, flanked by the Union flag and the Welsh dragon.

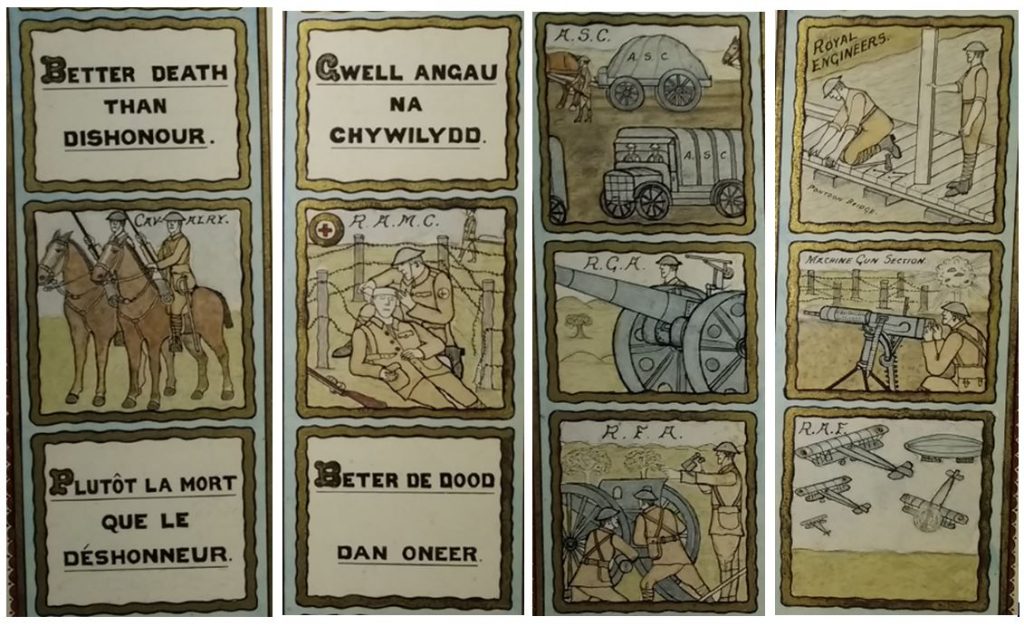

The design of the memorial of Tabernacl (on Woodfield Street – renowned as one of the most grandiose of all the chapels in Wales) is particularly interesting. It has the motto of the Welsh Regiment, “Better death than dishonour” in four languages (English, Welsh, French and Flemish) and ten militaristic pictures, including images of machine gunners and tanks.

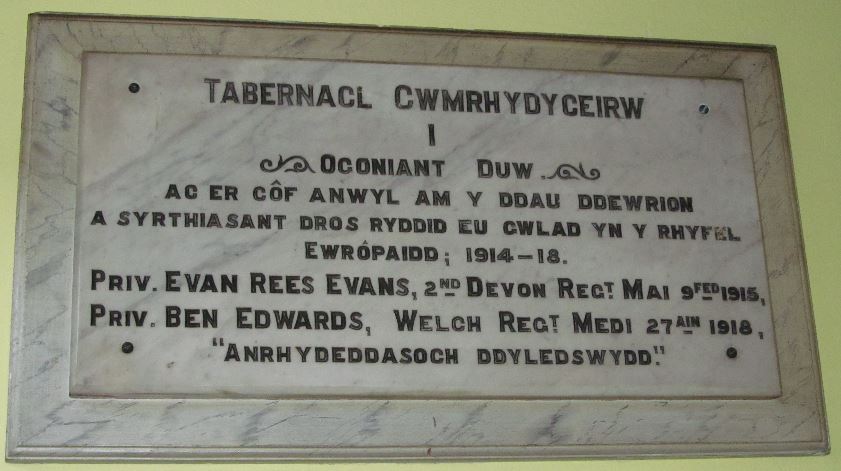

As well as the Roll of Honour, Tabernacl (Baptist) Cwmrhydyceirw has a tablet commemorating the two men from the chapel who died.

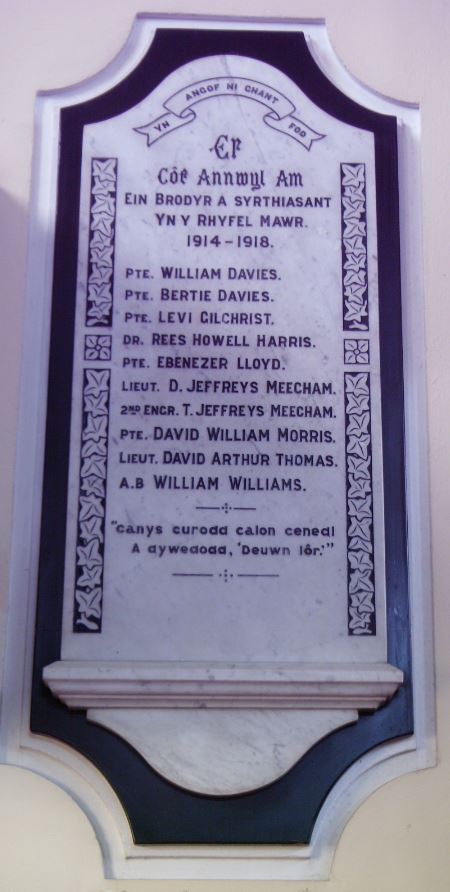

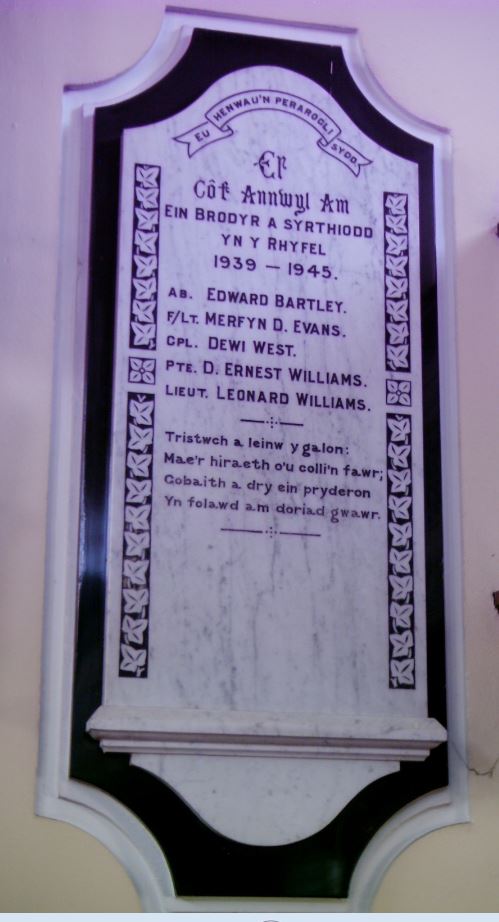

Bethania (Calvinistic Methodist) does not have a Roll of Honour – although the Annual Report for 1919 does give details of the 55 men from the chapel who served in the war. It has, on one side of the pulpit, a marble memorial to the 10 men from the chapel who died. It also has, on the other side, a similar memorial to the 5 men who were killed in the Second World War, as sad testimony to the fact that the Great War was not, after all, ‘the war to end wars’.

g.h.matthews February 5th, 2018

Posted In: Uncategorized