The Shields of the Earth: the WW1 memorial in Siloh, Landore

After almost 190 years, the grand Independent chapel of Siloh, in the Landore area of Swansea, closed its doors in January 2016. A hundred years ago the membership stood at around 640; at the end of the Second World War, there were over 600; when the chapel closed, the number of members was in single figures.

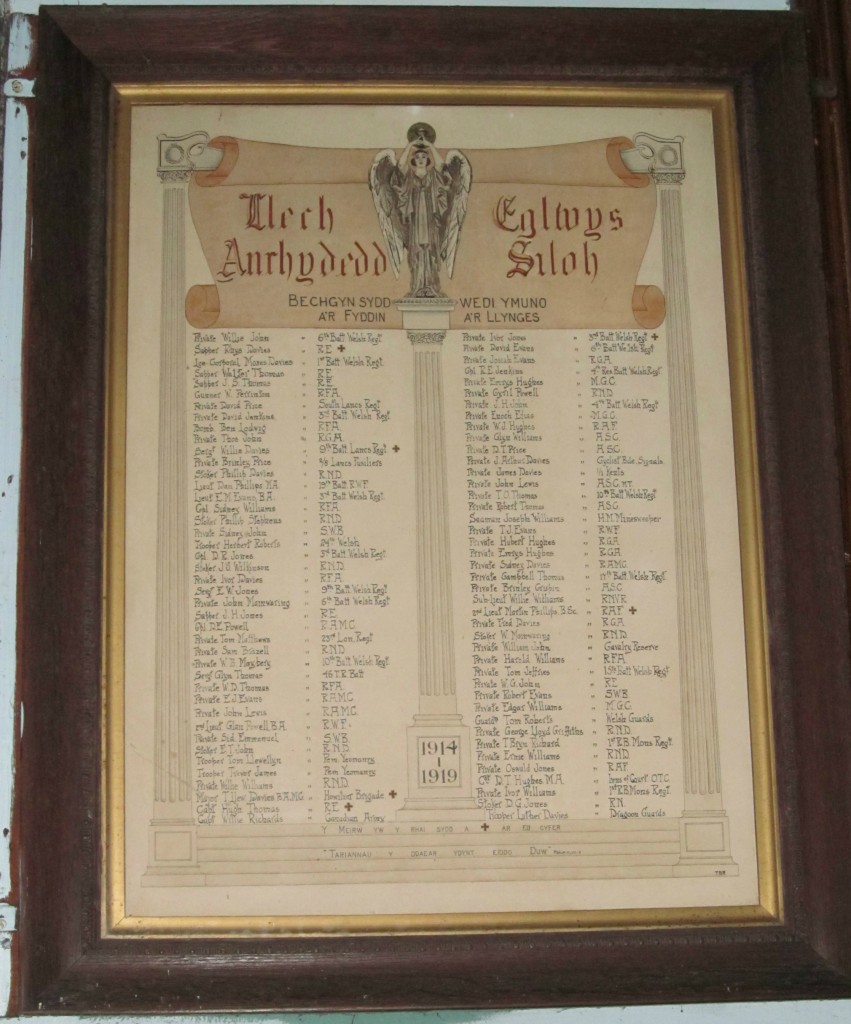

In the building’s vestry there was a roll of honour to remember the 84 men of the chapel who served in the armed forces between 1914 and 1918. This figure is not unusal for a chapel memorial in north Swansea – there are, for example, 81 names on the memorial at Caersalem Newydd, Treboeth, and 66 on the memorial at Carmel, Morriston.

The imagery on this memorial is interesting, but again it is similar to other examples.  Classical-style pillars can be found flanking the names in the memorials of chapels such as Mynydd Bach (north Swansea), Zoar (Merthyr), Graig (Merthyr), Libanus (Dowlais) and Carmel (Aberdare), to name just five. Similarly, angels adorn the memorials in Zoar (Merthyr), and Noddfa, Abersychan.

Classical-style pillars can be found flanking the names in the memorials of chapels such as Mynydd Bach (north Swansea), Zoar (Merthyr), Graig (Merthyr), Libanus (Dowlais) and Carmel (Aberdare), to name just five. Similarly, angels adorn the memorials in Zoar (Merthyr), and Noddfa, Abersychan.

The Biblical verse (Psalm 47:9) is not one of the common choices: ‘Tariannau y ddaear ydynt eiddo Duw’ (‘the shields of the earth belong unto God’ in the King James version) although similar sentiments can be found on chapel memorials all over Wales.

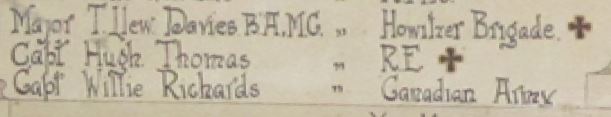

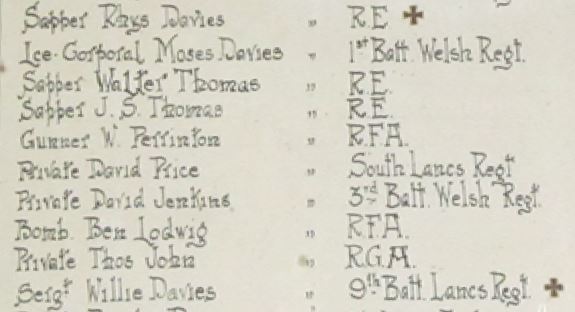

While looking at the servicemen listed, we know (thanks to the chapel’s annual reports) that 18 volunteered in 1914 and 10 in 1915. Conscription was introduced in early 1916 so we cannot tell how much choice the 25 who joined up that year had, nor the 15 in 1917 nor the 12 in 1918.

One of the men (Captain Willie Richards) served with the Canadian forces: again, there are plenty of similar examples across Wales of men who served with (in particular) the Canadian or Australian forces. This reflects the substantial emigration that had taken place from Wales to the dominions in the decade up to 1914.

One of the men (Captain Willie Richards) served with the Canadian forces: again, there are plenty of similar examples across Wales of men who served with (in particular) the Canadian or Australian forces. This reflects the substantial emigration that had taken place from Wales to the dominions in the decade up to 1914.

It is not just this ‘llech anrhydedd’ (literally ‘slate of honour’) that indicates the chapel’s viewpoint on the justice of the British cause. Letters were sent every Christmas by the minister, the Rev. Samuel Williams, to the soldiers and sailors of his flock, assuring them that Siloh supported them and prayed for them. When the men returned home on leave, the chapel organised meetings to welcome them: you can read here a report from January 1917 of a meeting when Private Tom Matthews was presented with a fountain pen by the Rev. Williams.

Unlike many other chapel memorials, the names of those who were killed are not listed separately, nor on another memorial, but a cross was added by the names of six men to show that they died in the war.

Unlike many other chapel memorials, the names of those who were killed are not listed separately, nor on another memorial, but a cross was added by the names of six men to show that they died in the war.

Although Siloh has closed its doors as a place of worship for the last time and the building is to be sold, the future of this memorial is secure, as it has been transferred to the care of West Glamorgan Archives.

g.h.matthews April 25th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

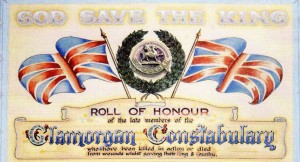

The Glamorgan Constabulary Roll of Honour

The ‘Welsh Memorials to the Great War’ project is interested in those memorials which commemorate the service of members of particular communities, be they chapels, clubs, schools or workplaces. Of course, many of these institutions have disappeared or been transformed over the intervening years. In terms of workplaces it is very difficult to find mines or industrial manufactories that are still going concerns.

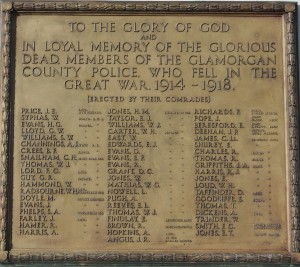

One institution that still has its place in society is the police force. Here there have been re-organisations, so that the old Glamorgan Constabulary has merged with the formerly independent police forces of Cardiff, Merthyr, Neath and Swansea to form the South Wales Police. The urban police forces have their own memorials to policemen who fell while serving in the First World War, but the focus of this article is the Glamorgan Constabulary.

Outside Police HQ  in Bridgend there stands an impressive memorial to the fallen, listing the 58 who were killed in WW1 and 28 who were killed in WW2.

in Bridgend there stands an impressive memorial to the fallen, listing the 58 who were killed in WW1 and 28 who were killed in WW2.

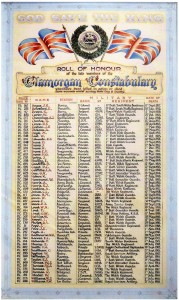

Usually, a striking WW1 Roll of Honour is on display inside the building –  but while some refurbishment is being completed this memorial is currently in the Cardiff station.

but while some refurbishment is being completed this memorial is currently in the Cardiff station.

This impressive memorial lists the 58 names and gives further details of their police service.

The South Wales Police First World War Project Group has been active in researching these men so that it become more than a mere list of names. A series of booklets are being produced, starting off with one which tells the story of those who fell in 1914.

Looking at the booklet about 1915, it is remarkable that five Glamorgan policemen and one Cardiff constable were killed on one day, 27 September 1915, the first day of the Battle of Loos (in Belgium, on the Western Front). Five more south Wales policemen died within a month in that vicinity.

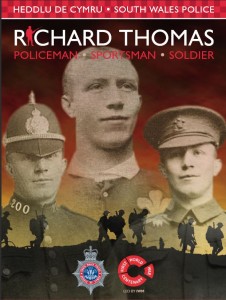

Another booklet tells of the connections between the police forces of South Wales and the Welsh Guards, and one further booklet focusses in on the story of Richard Thomas (known as Dick).

Born in Ferndale in 1881, he was a very well-known sportsman before the war, being capped as a forward four times for Wales between 1906 and 1909. He was part of the Wales team that won the Grand Slam for the first time, when they beat Ireland in March 1908. Although his reputation was as a hard-tackling forward, he occasionally also played as a back for the Glamorgan Police side. To show that he was a real all-rounder, he was also the Glamorgan Police heavyweight boxing champion on three occasions.

In August 1913 Dick was promoted to sergeant and was stationed at Bridgend. However, five months into the War he volunteered for the 16th Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, known as the Cardiff City Battalion. This was part of the ‘Welsh Army Corps’ – raised as part of the recruitment drive headed by Lloyd George with the aim of putting ‘a Welsh army in the field’. After training in Wales, the unit headed off for further training in Winchester before departing for the Western Front as part of the 38th (Welsh) Division.

The division was involved in a major battle for the first time at Mametz Wood, six days into the 1916 Somme campaign. The Cardiff City Battalion were among those ordered to make an assault across open ground to capture the heavily defended wood on 7 July. Dick Thomas was one of the battalion’s 300 casualties that day.

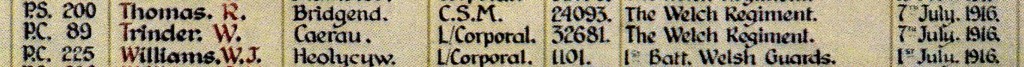

Looking at the Glamorgan Constabulary memorial, you will see details of some others killed in the same battle. Robert Harris (Cardiff City Btn, 7 July 1916), William Edward Trinder (Cardiff City Btn, 7 July 1916) and William Henry Loud (10th (1st Rhondda) Btn, Welsh Regiment, 10 July 1916) were killed as the Welsh took Mametz Wood; Edward Beresford (South Staffordshire Regt, 10 July) was killed nearby in a supporting action.

With thanks to Gareth Madge for his assistance

g.h.matthews April 18th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Obituaries and Memorials to the Soldiers of Tregarth

Tregarth is a village in the Ogwen Valley, Caernarfonshire. Its Wesleyan Methodist chapel, ‘Shiloh’ and church, ‘St Mary’s’ are still open and have memorials dedicated to those who lost their lives in the First

World War. The church also holds the Sunday school’s memorial and a stained glass window dedicated to the Brock brothers, whose father was the headmaster of the local school. The gates to the church are also a memorial to those from Tregarth who died during both world wars.

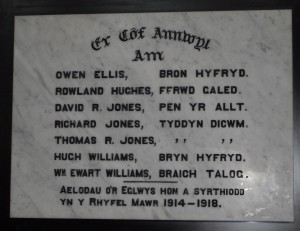

Shiloh’s memorial lists the names and homes of members of the congregation who died fighting the war (for example: Richard Jones – Tyddyn Dicwm). It was necessary to include the street or farm where the fallen had lived, as the community identified them by their place of residence rather than by their surname. Therefore, Richard Jones would probably have been known as Richard Tyddyn Dicwm. The gates outside St. Mary’s and the Sunday school memorial also note where the soldiers had lived in Tregarth. This was also important because a number of the soldiers had the same surname – there are 43 names on the Sunday school memorial, 13 of whom are ‘Jones.’

Shiloh’s memorial lists the names and homes of members of the congregation who died fighting the war (for example: Richard Jones – Tyddyn Dicwm). It was necessary to include the street or farm where the fallen had lived, as the community identified them by their place of residence rather than by their surname. Therefore, Richard Jones would probably have been known as Richard Tyddyn Dicwm. The gates outside St. Mary’s and the Sunday school memorial also note where the soldiers had lived in Tregarth. This was also important because a number of the soldiers had the same surname – there are 43 names on the Sunday school memorial, 13 of whom are ‘Jones.’

St. Mary’s memorial, by contrast, seems less concerned with remembering the soldiers as part of the local community, and more concerned with showing their important role in the Great War. The memorial does say where the soldiers lived. In the majority of cases it does not record the first names of the deceased. Instead, it lists their rank in the army; first initial; surname; area in which they fell and the year they died. The stained glass memorial to the Brock brothers in St. Mary’s echoes this focus on military accomplishments. Although we know from the Sunday school memorial that they lived at Sunnyside, the inscription on the stained glass makes no reference to this. It reads: ‘In loving memory of Lieut. Herbert Leslie Brock (BA Wales) 20th Div. MGC. Killed in action in France April 10th 1918 age 28, and Private Ivor James Baxter Brock 14th Batt. R. W. F. killed in France Sept. 1st 1917 age 19. “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends.” S. John XV 13.

Different memorials commemorated men in different ways, and the same can be said of newspaper obituaries. This project seeks (among other things) to analyse memorials from all over Wales to see if it is possible to identify patterns in their styles and wording. For example, was including the soldier’s home address on a memorial a trait unique to north Wales, or was it common across rural Wales? Did all Anglican churches note where and on what date members of their congregation had been killed in action? Further research also needs to be done on whether the religious denomination or political outlook of the newspapers had an influence on the style of obituary they published.

Below are examples of Tregarth men’s obituaries from three newspapers. Y Llan was a bilingual Anglican newspaper, whilst Y Gwyliedydd Newydd was Wesleyan. Y Genedl was more political than religious. It supported the Liberal party, but welcomed contributions which reflected the socialist point of view.

Both Y Llan and Y Genedl’s obituaries seem to stress that the fallen were brave men who had fallen for king and

county. Whilst Y Llan (28/4/1916, p. 7) extended its deepest sympathy to David Williams’s whole family, especially his widow, his young children and his mother, they believed that ‘ond y mae cysur i’w gael wrth feddwl ei fod wedi marw wrth wneud ei ddyletswydd’ (but there is comfort to be had in the thought that he has died doing his duty). A month later, Y Genedl (23/5/1916, p. 8) was even more emphatic that the soldiers were dying for a just cause. It’s article was about a memorial service to Richard Price Jones, but in the middle of the article it refers to all soldiers involved in the war: ‘Da gweled yr ardalwyr yn gollwng dagrau hiraeth, ac o barch, ar ôl y bechgyn sydd yn rhoddi eu bywydau i lawr i gadw y gelynion rhag gwneud ein gwlad fel Belgium, Serbia a Pholand.’ (It is good to see the locals shedding tears of loss and of respect for the boys who have given their lives to prevent the enemy from making our country like Belgium, Serbia and Poland.’) Richard Price Jones’s memorial service was held at the Calvinistic Methodist chapel in Tregarth, but unfortunately I do not know if the chapel is still in use or if any memorials are preserved there.

By contrast, the obituaries in Y Gwyliedydd Newydd seemed less certain that the Great War was a just cause that was worth the cost. It also acknowledged that not all soldiers on the battlefield wanted to be there. My research so far has not been very extensive, so the first obituary I found relating to a soldier from Capel Shiloh is from September 1916. Conscription had been introduced in March 1916, and attitudes towards the war in Britain as a whole were less fervently patriotic than in the hopeful days of 1914. Also, as Dafydd Roberts has explained in his article, ‘”Dros ryddid a thros ymerodraeth” Ymatebion yn Nyffryn Ogwen 1914-1918’ (“For Freedom and for Empire: reaction in the Ogwen Valley 1914-1918,’ Caernarvon Historical Society Transactions, 1988-9 p. 107- 123), the residents of the Ogwen valley had been reluctant to enlist since the outbreak of war. Methodism in pre-1914 Wales had a strong pacifist tradition, which may also have influenced the newspaper’s views about the war. Y Gwyliedydd Newydd’s coverage of Rowland Hughes’s memorial service (12/9/16, p. 6) refers to the battlefield as ‘faes y gyflafan ofnadwy’ (the field of awful massacre). When Owen Ellis was killed at the front, the paper (30/1/1917, p. 7) played with the phrase ‘maes y gad’ (battlefield) calling it instead ‘maes y gwaed’ (field of blood). By the time David Richard Jones was killed (2/7/1918, article published 24/7/1918, p. 8), Y Gwyliedydd Newydd was referring to the whole war as ‘y gyflafan erchyll yma’ (this horrific massacre).

In two articles about members of Shiloh’s congregation who had died at the front, the paper makes it quite clear that they had not enlisted because they believed in the glory of war. The first, Rowland Hughes’s (12/9/16, p. 6), stated that he ‘Ymunodd a’r fyddin o argyhoeddiad dwfn. Methai a chysgu’r nos gan faint bwysai ar ei feddwl. Cychwynnodd i’r chwarel at ei waith, troes yn ei ôl, a cherddodd i Fangor i ymuno a’r fyddin, – “yr wyf i fod i listio, meddai, i ymladd dros gyfiawnder.” (He joined the army from deep conviction. He could not sleep at night because of the weight on his mind. He started towards his work at the quarry, turned around, and walked to Bangor to enlist in the army, – “I am going to enlist, to fight for justice”.) Although he had eventually decided to fight for his principles, the newspaper makes it clear that this was not an easy decision to make. The second example is Owen Ellis (30/10/17, p. 7). When describing his character, Y Gwyliedydd Newydd said he was: ‘un o’r bechgyn tyneraf ei ysbryd, a pharatoaf ei gymwynas. Er iddo farw’n filwr ar faes y gwaed, nid milwr mohono wrth anianawd. Yr oedd o duedd enciliedig, gwell ganddo wrando na llefaru. Er hynny, pan alwyd arno i gyflawni’r annymunol gwnaeth hynny yn ffyddlon a theyrngarol. Da gennym glywed gan ei Gaplan iddo farw fel y bu fyw, yn llawn arwriaeth.’ (He had one of the gentlest souls, and was always happy to help. Although he died a soldier on the field of blood, he was not a soldier at heart. He was of a retiring nature, preferring to listen than to preach. Despite this, when he was called upon to do the objectionable he did that faithfully and loyally. We are glad to hear from his Chaplain that he died as he lived, full of heroism.) Although this extract refers to Owen ‘doing his duty’ and ‘dying a hero’ it also, I think, makes it explicitly clear that he should not have died ‘on the field of blood.’

This article has only looked very briefly at the some of the memorials in one village. There is far more scope for others to find out more about the memorials and obituaries in their own local communities.

Meg Ryder April 11th, 2016

Posted In: chapels / capeli, memorials

Tags: Dyffryn Ogwen, Tregarth

The Monmouthshire Regiment and the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge by Shaun McGuire

It is possible that the total of 85 men from Newport killed on 8 May 1915 is the greatest loss suffered by any Welsh town in a single day in the First World War. They were part of the Battle of the Frezenberg Ridge, which was part of what has become known as the Second Battle of Ypres.

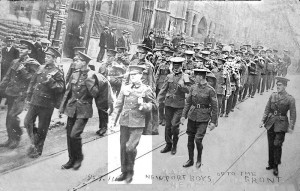

This photograph shows men marching down Stow Hill from the Drill Hall in the summer of 1914: the caption says ‘Newport boys off to the front’. The man highlighted at the front is Job William White, who was one of those killed on 8 May 1915. Further behind him is John Albert Pope, who was killed three years after the photograph was taken – on 17 June 1917. It was at the Drill Hall in Stow Hill, Newport that the First Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment recruited soldiers, and these men (along with the other two battalions in the regiment) became heavily involved in the second Battle of Ypres, which began on 22 April 1915.

This photograph shows men marching down Stow Hill from the Drill Hall in the summer of 1914: the caption says ‘Newport boys off to the front’. The man highlighted at the front is Job William White, who was one of those killed on 8 May 1915. Further behind him is John Albert Pope, who was killed three years after the photograph was taken – on 17 June 1917. It was at the Drill Hall in Stow Hill, Newport that the First Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment recruited soldiers, and these men (along with the other two battalions in the regiment) became heavily involved in the second Battle of Ypres, which began on 22 April 1915.

On 8 May the Monmouthshire Regiment were trying to defend the Frezenberg Ridge from a ferocious German attack. By the end of the day, the Regiment had lost 211 men and officers – 150 from the First Battalion, 19 from the Second and 42 from the Third. By the end of May the three battalions had lost a total of 515 men, with the Third Battalion suffering the greatest losses.

It was during this battle that Captain Harold Thorne Edwards replied to the German’s offer of surrender with the words, “Surrender be damned” and he and his men made the ultimate sacrifice. The scene of Captain Edwards and his men’s last stand is depicted in Fred Roe’s painting entitled “Surrender be damned” which was painted in 1935 after being commissioned by the South Wales Argus. It shows Captain Edwards firing his revolver at the advancing Germans. I believe the painting is now being displayed at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery after being hung in the foyer of Newport City council’s civic centre for many years.

battle that Captain Harold Thorne Edwards replied to the German’s offer of surrender with the words, “Surrender be damned” and he and his men made the ultimate sacrifice. The scene of Captain Edwards and his men’s last stand is depicted in Fred Roe’s painting entitled “Surrender be damned” which was painted in 1935 after being commissioned by the South Wales Argus. It shows Captain Edwards firing his revolver at the advancing Germans. I believe the painting is now being displayed at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery after being hung in the foyer of Newport City council’s civic centre for many years.

During research for the Newport’s War Dead website I came across a photograph in the South Wales Argus, 9th May 1947, of Alderman Mrs. Sarah J Haywood dedicating a plaque in front of members of the Old Comrades Association of the Monmouthshire Regiment in Bellevue Park, Newport. This may have been a plaque to replace an original one which would have been attached to a grove of eight may trees (hawthorns) that were planted in the 1920s as a memorial to those of the Monmouthshire Regiment that died on the 8th May 1915.

My inquiries about this memorial established that the trees had now either died off or were cut down. Unfortunately this meant that an event that caused great sorrow and sadness to the family and friends of these Newport men was now no longer commemorated.

I then started a campaign to get a new memorial to commemorate the battle of Frezenberg Ridge and the men who died on the 8th May 1915. My campaign was taken up by councillor Charles Ferris and numerous other friends including my daughter, Shelley. Finances were raised and on the 8th May 2015 a new memorial was dedicated on the banks of the river Usk opposite the Blaina Wharf pub in Newport. The event was attended by many dignitaries and military personnel.

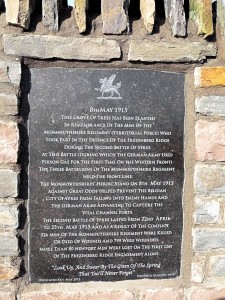

Inscription on the Memorial on Usk bank

8th May 1915

THIS GROVE OF TREES HAS BEEN PLANTED/ IN REMEMBERANCE OF THE MEN OF THE/ MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT (TERRITORIAL FORCE) WHO/ TOOK PART IN THE DEFENCE OF THE FREZENBERG RIDGE/ DURING THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES./

AT THIS BATTLE (DURING WHICH THE GERMAN ARMY USED/ POISON GAS FOR THE FIRST TIME ON THE WESTERN FRONT)/ THE THREE BATTALIONS OF THE MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT HELD THE FRONT LINE./ THE MONMOUTHSHIRES’ HEROIC STAND ON 8TH MAY 1915/ AGAINST GREAT ODDS HELPED PREVENT THE BELGIAN/ CITY OF YPRES FROM FALLING INTO ENEMY HANDS AND/ THE GERMANY ARMY ADVANCING TO CAPTURE THE VITAL CHANNEL PORTS./

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES LASTED FROM 22ND APRIL/ TO 25TH MAY 1915 AND AS A RESULT OF THE CONFLICT/ 526 MEN OF THE MONMOUTHSHIRE REGIMENT WERE KILLED/ OR DIED OF WOUNDS AND 799 WERE WOUNDED./ MORE THAN 80 NEWPORT MEN WERE LOST ON THE FIRST DAY/ OF THE FREZENBERG RIDGE ENGAGEMENT ALONE./

Look Up, And Swear By The Green Of The Spring/ That You’ll Never Forget” – SIGFRIED SASSOON, 1919

Earlier on the same day, a new wooden sculpture was unveiled at the old drill hall on Stow Hill, where these men had been recruited. It depicts the scene from Fred Roe’s painting of Captain Harold Thorne Edwards and his men’s stance against the oncoming German attack.

Meg Ryder April 4th, 2016

Posted In: memorials

Tags: Monmouthshire Regiment/ Catrawd Sir Fynwy, Newport/Casnewydd