The Mond Nickelworks WW1 Memorial

For well over a century, the Mond nickelworks has been a major landmark and an important employer for the people of Clydach, in the lower Swansea valley. The works first produced nickel in 1902, using a process pioneered by a German chemist-entrepreneur named Ludwig Mond whose statue stands nearby, surveying his creation. Although the ownership of the works has changed over the decades, so that it is now operated by Vale, a Brazilian company, to locals it is simply ‘the Mond’.

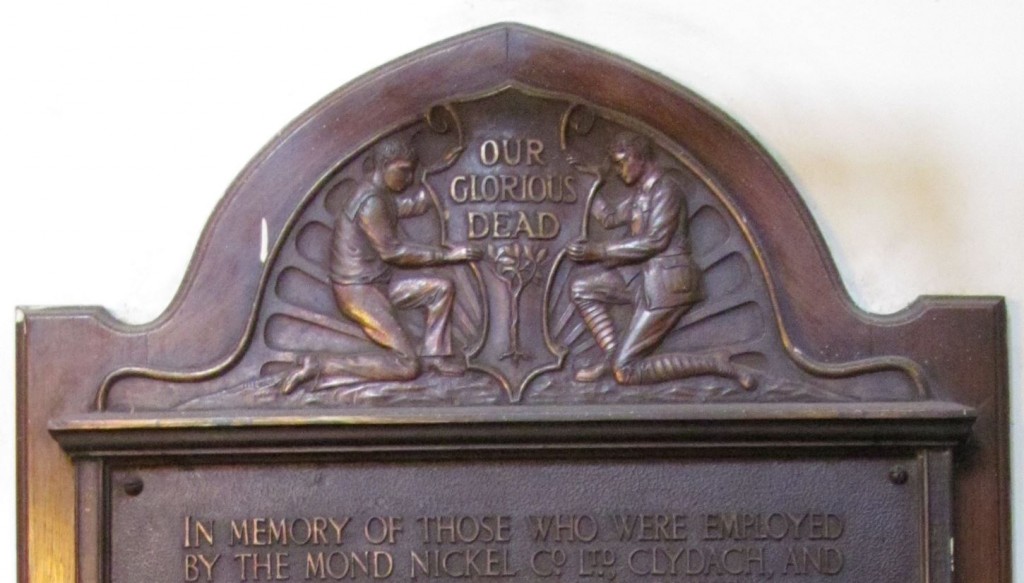

On the way into the Mond Community Centre (attached to the works) you walk past two memorials, commemorating the 33 men associated with the company who died in the First World War, and the 19 who were killed in the Second World War.

The number of names on the WW1 memorial is striking, although it is only a fraction of the 450 Mond employees who volunteered or (after 1916) were conscripted into the armed services. The figures indicate that 250 employees (out of 850) volunteered to serve in the Armed Forces in the first few months of the war. Besides any other reasons for volunteering, they were encouraged and supported by the company’s management, who promised to pay half-wages to the families of married volunteers, and also to support the dependents of single men who joined up. Of course, the product of the Mond, refined nickel, was in high demand at wartime and it was a profitable time for the company. For more details of this, see this blog from 2014 on the BBC’s website.

One consequence of the flow of men from the Mond into uniform was that women were recruited to work in the manufacturing process for the first time: thus the list of names on the memorial is only part of the story of how the war affected the local community.

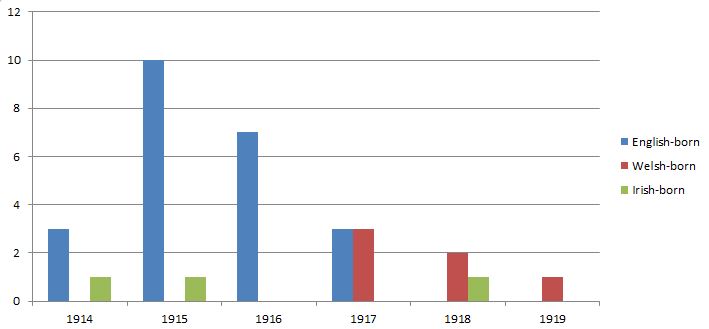

Excellent research work by local historian Bill Hyett into the details of the 33 men who died shows some interesting patterns that need to be carefully examined and explained.  Mr Hyett has found biographical and service details of all but one of the men. The statistic that stands out from this research is that over two thirds of them – 23 – were English-born. A further three were Irish-born, meaning that only six were Welsh-born. This does not reflect the general workforce at the Mond, where the majority of the names on the employment register are clearly Welsh.

Mr Hyett has found biographical and service details of all but one of the men. The statistic that stands out from this research is that over two thirds of them – 23 – were English-born. A further three were Irish-born, meaning that only six were Welsh-born. This does not reflect the general workforce at the Mond, where the majority of the names on the employment register are clearly Welsh.

A clue to explain this discrepancy can be found when studying the patterns of when these servicemen were killed. Of the four who died in 1914,three were English and one Irish; in 1915, ten English and one Irish were killed; all of the seven casualties in 1916 were English-born. Then in 1917 three English-born and three Welsh-born died; in 1918 two Welsh and one Irish and the final casualty, who died in 1919, was Welsh.

This demonstrates that most of those who joined up earliest in the war, and who were thus most likely to be killed in it, were English-born. Most of these had lower-paid unskilled jobs at the plant, and some had not been working there very long. One example is Reginald Edwards, born at Erdsley, Hereford. His employment at the Mond was very brief, as he started work on 11 August 1914 and volunteered for the Royal Field Artillery in September 1914. Thus those who were most likely to join up early in the war were the unskilled labourers, many of whom had moved to Clydach from England. The local-born workers often had better-paid, higher-skilled jobs, and so were less likely to volunteer for the armed forces.

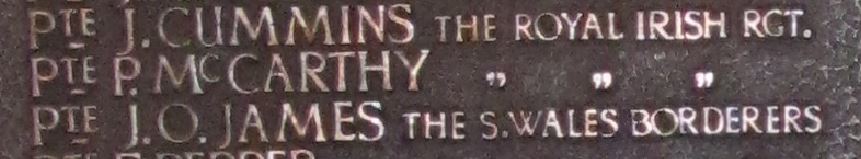

Here are details from Mr Hyett’s magnificent research of two individuals which give an idea of the human stories behind the list of names on the metal plaque. The first of the Mond casualties was Tipperary-born Peter McCarthy, who was about 25 years old when he began work at the Mond in March 1914. He must have been an army reservist, called up in August 1914, for he was killed on the Western Front on 7 October 1914: he has no known grave.

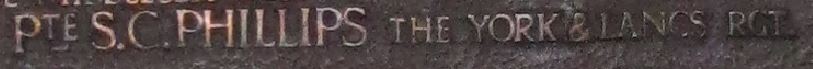

The final Mond casualty was Sidney Phillips (noted on the memorial as S. C. Phillips, though Mr Hyett’s research has shown that his middle name was George). He was Swansea-born and lived in Ebenezer Street, Swansea with his wife and three children. Sidney was one of those who volunteered in 1914, initially serving with the Welsh Regiment before transferring to the York and Lancs Regiment. He suffered a gun-shot wound to the thigh in May 1916 but recovered, only to fall victim to a gas attack in France. He was invalided home and discharged from the army in September 1918, but died on 17 April 1919 and received a military funeral in Swansea’s Dan-y-Graig cemetery.

g.h.matthews May 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Patterns of Memorialisation

One of the patterns that has become clear as we gather material from around Wales for the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project is that patterns of memorialisation can be local. That is, particular communities in certain areas will have the same kinds of memorials to those who served in the First World War.

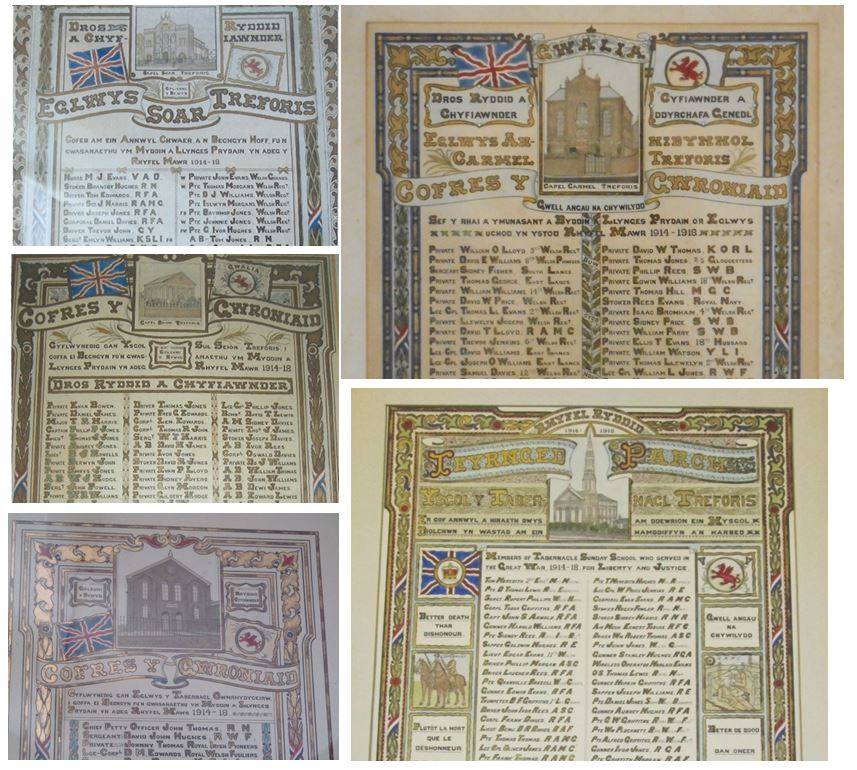

One example can be seen in the nonconformist chapels of Morriston. Another blog post looks at these in more detail – look at how similar the various chapel memorials are.

These five memorials have all been designed by the same man, and they all have an image of the chapel building to the fore, flanked by the Union flag and the Welsh dragon.

Another patch of Wales where a number of interesting chapel memorials have survived is the Pontypool area. Below are five examples of memorials from Baptist chapels in the area which, although different in design, share some important features.

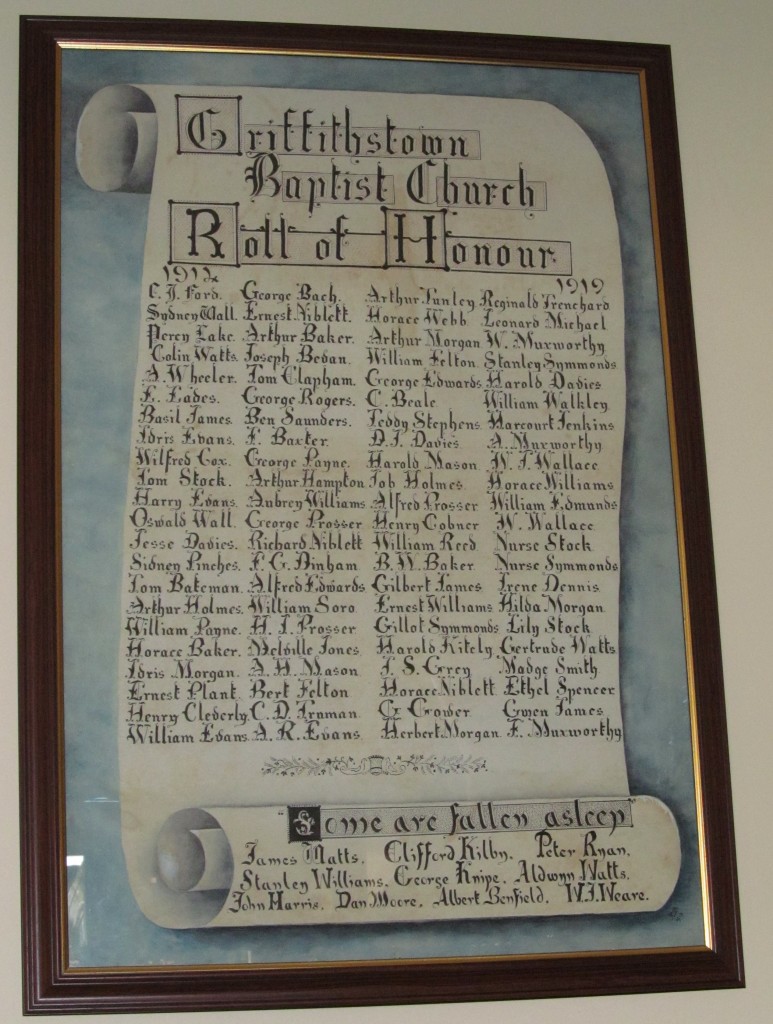

The memorial in Ebenezer Baptist chapel, Griffithstown (south of Pontypool), was designed by Mrs K. Davies, the minister’s wife, and was unveiled in March 1919. It lists the names of 78 men and then ten women who served, and then names the ten men who died on active service. (The final woman on the list is F. Muxworthy: this is almost certainly Frances Muxworthy of Kemeys Street, Griffithstown, who served with Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. This also suggests that two of the men listed are her brothers, Arthur and William Muxworthy).

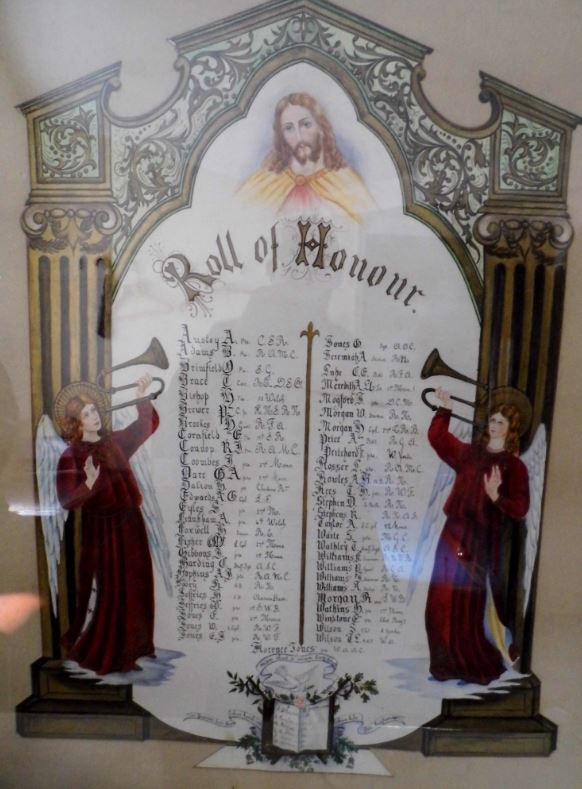

In Merchant’s Hill Baptist chapel, Pontynewynydd, a Roll of Honour was unveiled in  October 1919, naming five men who died, and 47 men and one woman who served.

October 1919, naming five men who died, and 47 men and one woman who served.

There is also in this chapel a memorial which names six men and one woman who died.

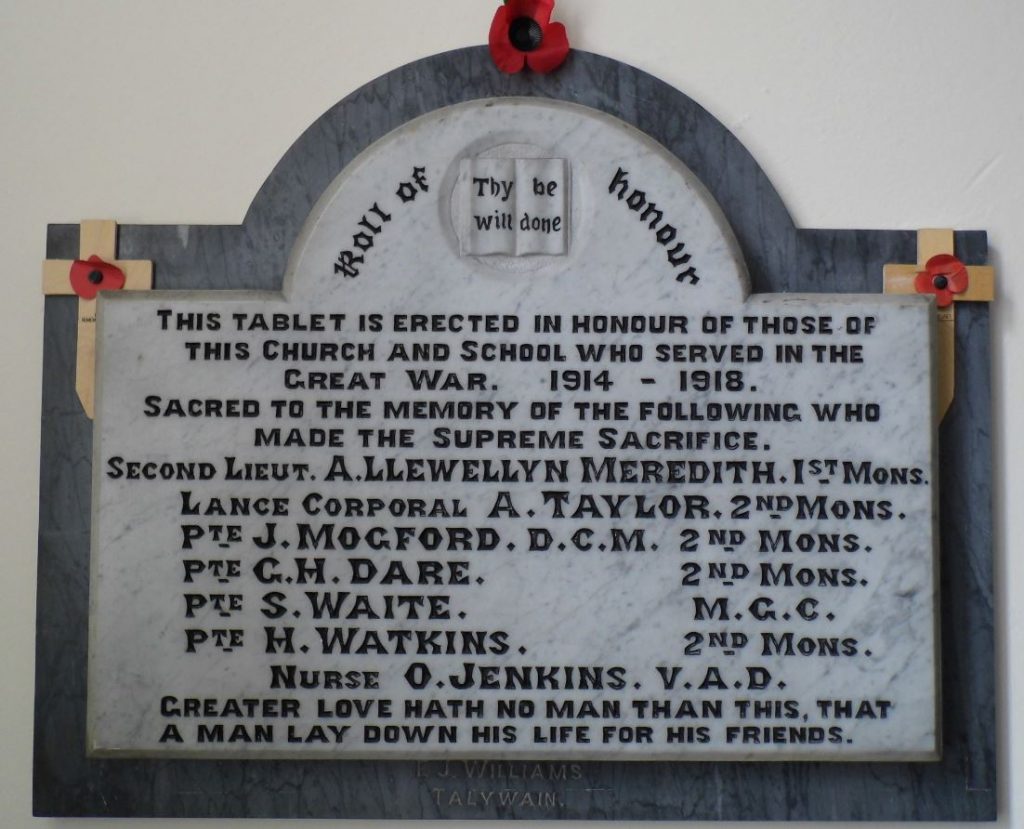

Moving north of Pontypool to Talywain, there is Pisgah chapel. Here the memorial is in marble, and it lists three men who were killed in action, and then gives the names of 44 men and four women who served.

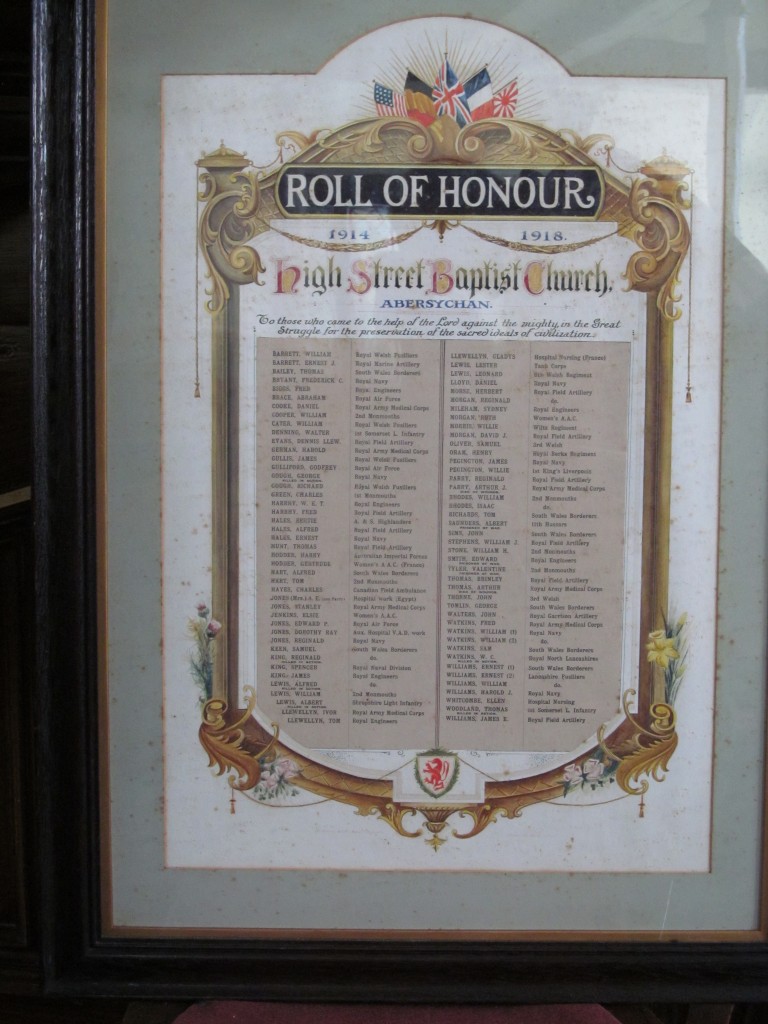

Just down the road in Abersychan there is the High Street English Baptist chapel.

The list here is alphabetical (unlike the list in the others mentioned here) and it contains 85 names, including seven women. Eight of the men were killed in the war.

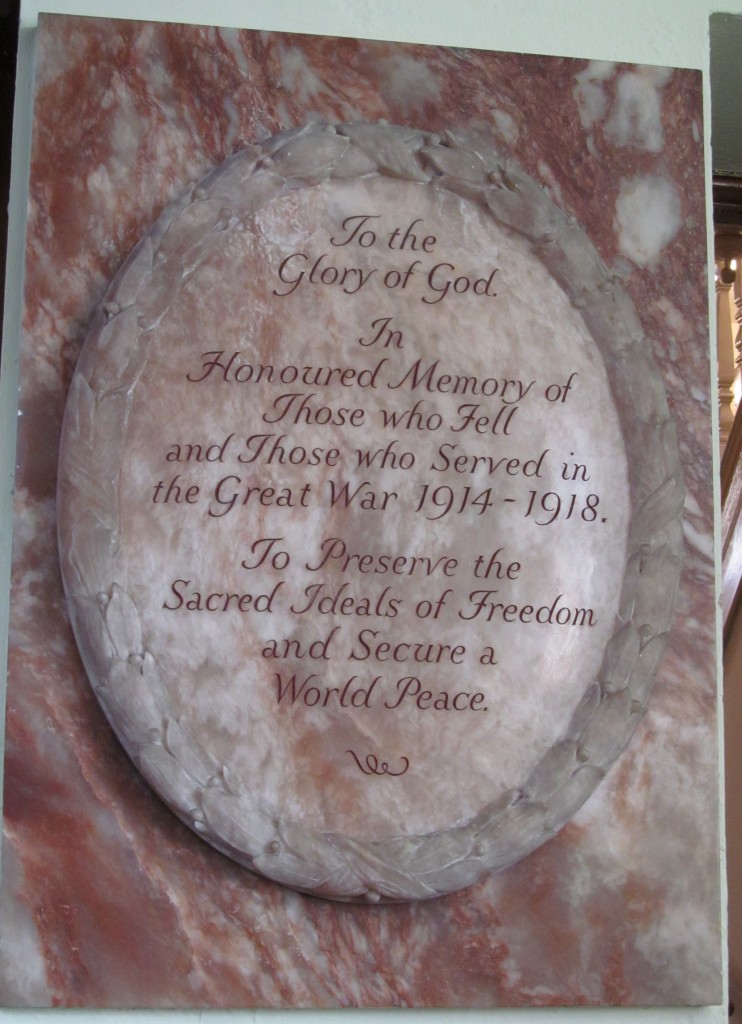

On prominent display in the chapel there is also a marble tablet celebrating the peace that came at the war’s end.

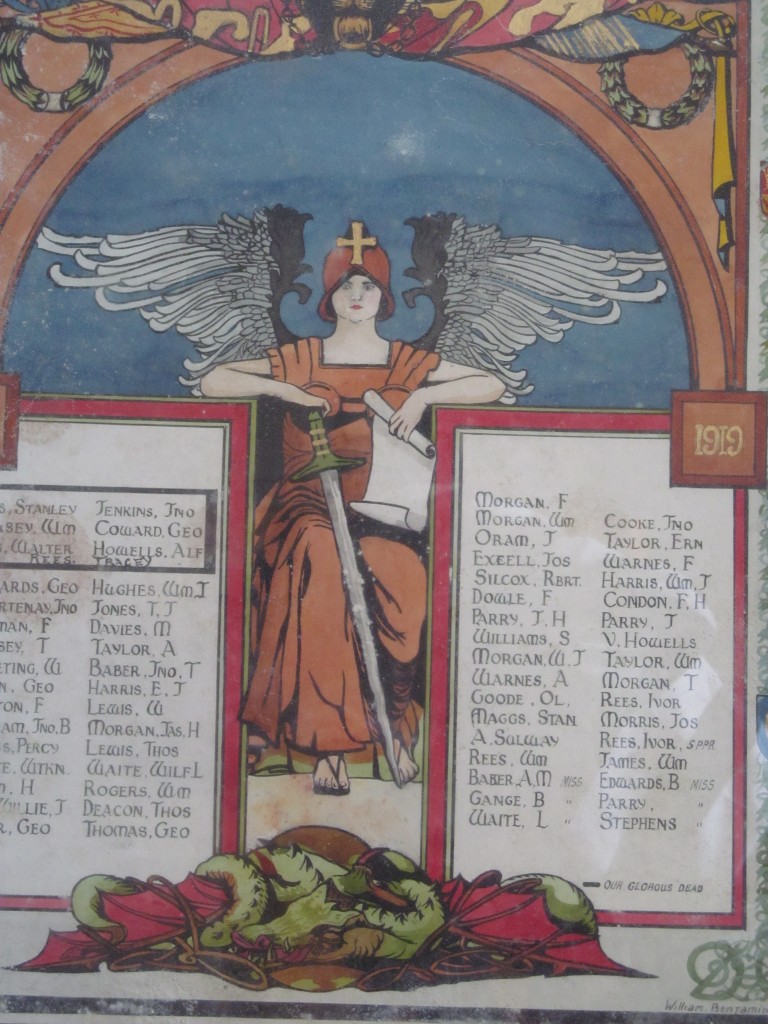

A stone’s throw away from High Street chapel is Noddfa, yet another Baptist chapel. The memorial here lists seven men who died and then the names of 53 other men who served and six women.

In visual terms, this is obviously the most striking of the five. The memorial, designed by William Benjamin John of Abertillery, has some very strong symbolism. The central figure is an angel; above is a lion with chains in its mouth; at the bottom is a slain dragon. This is probably the most vivid image of a chapel memorial so far collected by the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project.

Having noted the differences in the appearance of the four memorials described, it is also worth dwelling on their similarities. All of these memorials honour those who served, as well as mourning those who died. (Around a half of the Welsh chapel memorials so far gathered are Rolls of Honour which list all who served). All of these memorials name the women who served (mainly as nurses, but also in units such as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) – whereas in general only around a third at most of Welsh chapel Rolls of Honour include the names of women.

Perhaps there is a case of imitation here, or maybe we could even say competition. The chapels were proud of their communities’ contribution to the war effort and they wanted to demonstrate it. Thus as well as the clear motivation of honouring those who served in the war, there was also an element of pride in both the execution of the memorial and in the length of the list of chapel members who had ‘done their duty’.

g.h.matthews May 9th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized