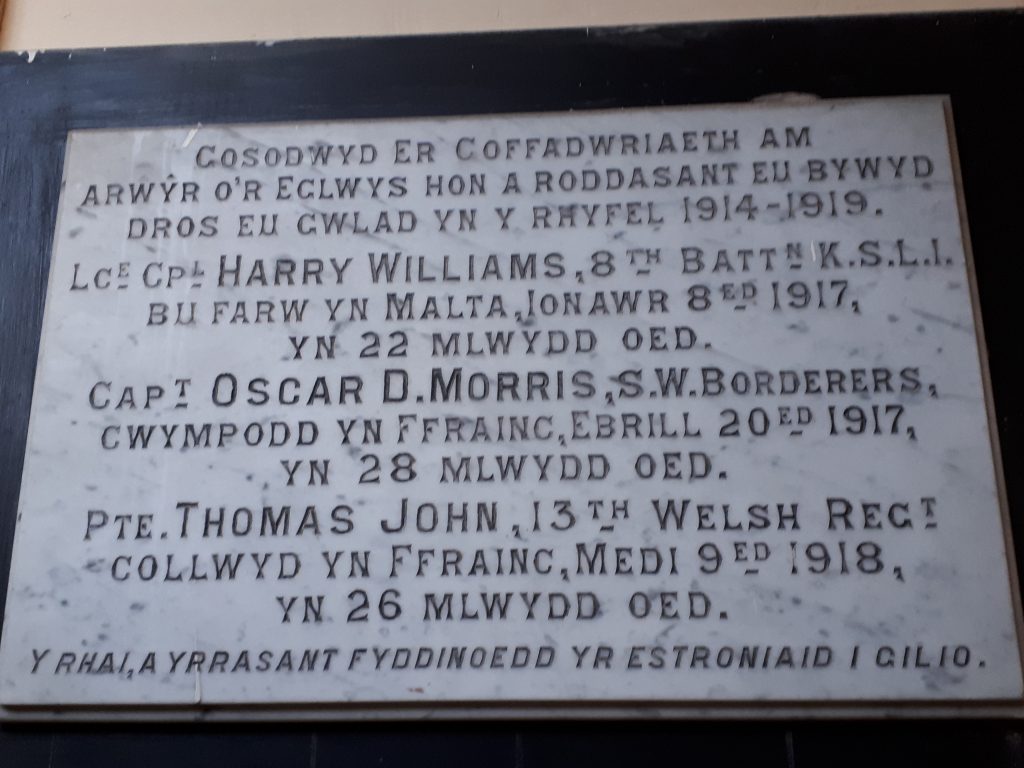

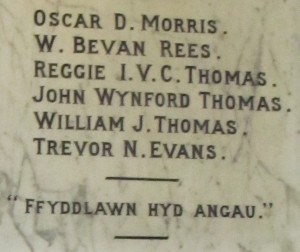

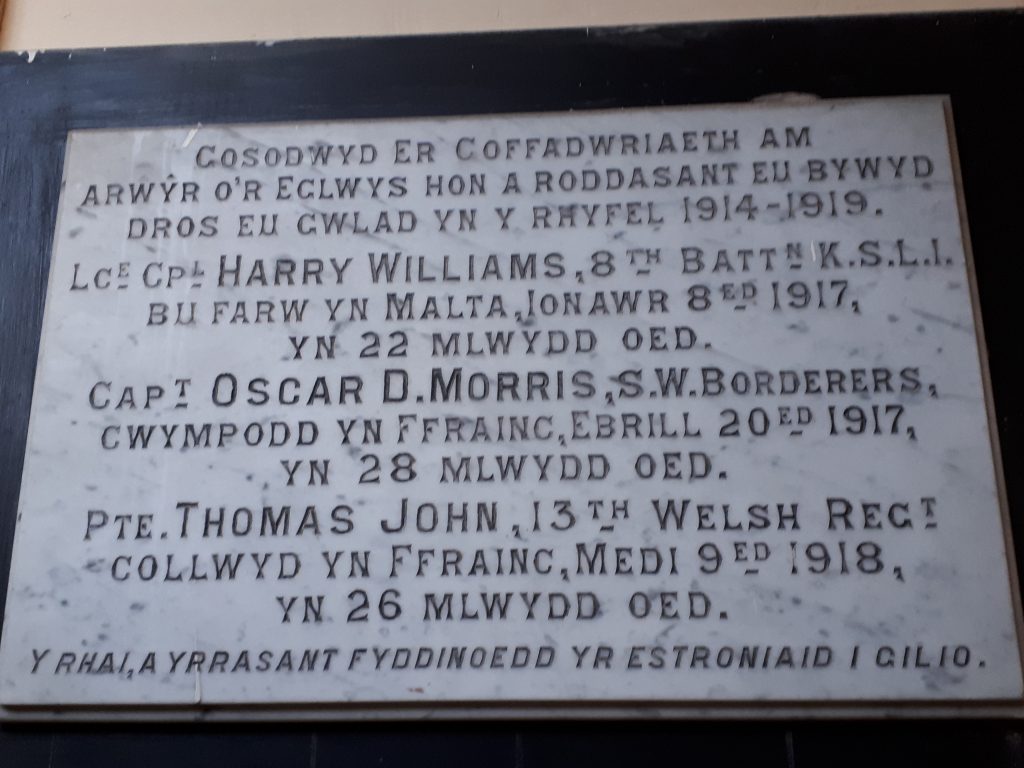

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

The memorial itself is impressive, being carved in marble.

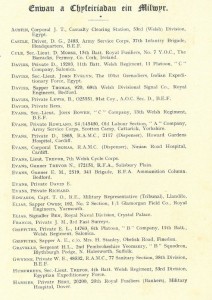

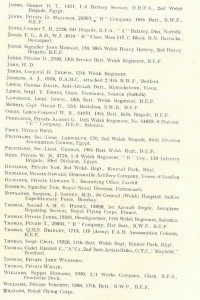

There are no records to indicate whether the chapel displayed a ‘Roll of Honour’ as the war was being fought, to highlight the contribution of a large number of the congregation to the war effort. However, the chapel’s Annual Reports do note the names of all the men who enlisted, and so we can trace how the war had a deeper effect every year on the congregation. There were 45 names on the list at the end of 1915, 62 by the end of 1916 and 66 in 1917 (including four who had been killed). The membership of the Tabernacl during the war fluctuated from around 520 to 560, so the total of 66 represents a sizeable proportion of the young male membership of the church.

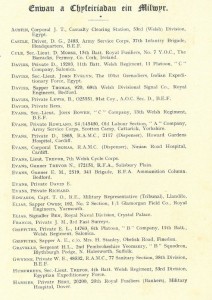

List of chapel members serving in 1916

We can also see how the War’s impact became deeper and more painful from the minister’s comments in the reports. At the end of 1914 there was more discussion about the fire that had damaged the chapel than about the War, but the Rev Charles Davies’ comments became ever more emotional as the war dragged on and took an ever-increasing number of young men from his flock. Looking back upon 1916, he wrote that the young men left a large gap, and that their valuable contribution to the life of the chapel was deeply missed by those who were left. However, there is no doubt that the minister considered the war to be just, as he used such words as ‘teyrngarwch’ (loyalty), ‘dewrder’ (courage) and ‘aberth’ (sacrifice) to describe the men’s contribution to the war effort. He declared that as they faced the dangers and discomforts of the war, they were fighting ‘er amddiffyn ein gwlad, a sicrhau buddugoliaeth i gyfiawnder a gwir rhyddid yn ein byd’ (to defend our country, and to ensure a victory for justice and for the true freedom of our world).

In the lists of the men there is information about where a number of them were serving. At the end of 1916 a large number were in training camps in England or Wales; 14 with the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) on the Western Front; six in Egypt; four in Salonica and one in Bombay.

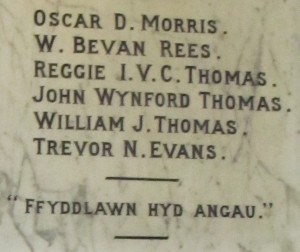

The first name on the memorial is Oscar D. Morris. It is possible to find a great deal of information about him: the letter he wrote as he sought to join the Welsh Army Corps are available on the Cymru1914 website – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/archive/4089505

One can also find a report on his promotion to lieutenant (August 1915 – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886208/7/ART121) and then reports on his death on the Western Front on 21 April 1917 (http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886989/1/ART11 and http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886999/3/ART35 ).

Oscar’s name is also to be found on the memorial in his home chapel – Salem Nantyffyllon.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

Reggie I.V.C.Thomas is the next name: he died on 24 November 1917 aged 19, while serving on the Western Front with the South Wales Borderers. He has no known grave, but his name is on the Cambrai memorial.

One can find John Wynford Thomas as a 12 year old boy in the 1911 Census, living in Lampeter Velfrey. There is no indication of when he moved to Cardiff, but he enlisted in the city, joining the South Wales Borderers. He was killed in Flanders on 31 October 1917.

Despite his common name, it is certain that the William John Thomas named on the memorial was an 18 year old who died on 11 July 1918 while serving with the Army Service Corps. He is buried in Cathays Cemetery, Cardiff.

However, the final name on the memorial is not on the list of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. According to the Tabernacl’s records he was a soldier in 1916, serving as a Gunner with the RFA (Royal Field Artillery) on Salisbury Plain. The chapel’s report says that he died on 18 February 1919.

g.h.matthews March 22nd, 2016

Posted In: chapels / capeli, memorials, Uncategorized

Tags: chapels / capeli, memorials, WW1

5 Comments

Since the autumn of 2015, the project Welsh Memorials to the Great War has been preparing to investigate the range of First World War memorials in Wales. Generously funded by the Living Legacies Engagement Centre, this project aims to begin to fill a gap in our knowledge and appreciation of ‘unofficial’ war memorials in Wales. Although a lot of work has been done on commemoration of the war in Wales, the tendency has been to focus on the ‘official’ memorials. The available databases do a good job of listing these, what you might call the ‘village green’ memorials, but they are very patchy when it comes to memorials that were set up by chapels, workplaces, schools and societies.

As well as creating and sharing a database, the project will also explore different ways in which these memorials can be analysed by researchers. The database could be used to facilitate:

– a ‘micro-history’, focussing in closely on one memorial and doing a biographical analysis of the names listed.

– a study of the distribution of the memorials, and how there are different patterns of commemoration across Wales

– a study of the iconography of the memorials, and again how this differs across regions

– looking at patterns of inclusion, for instance by examining those memorials that list women as well as

men.

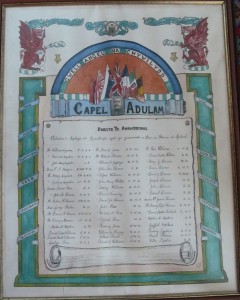

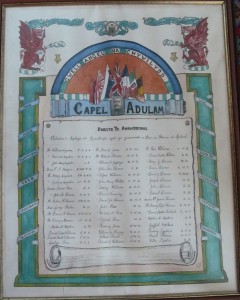

As we work to get the project up-and-running, I have continued to gather images of chapel memorials. I find these very enlightening as to the attitudes of people and communities across Wales to the war. Of course, prior to August 1914, these institutions were strongly anti-militaristic, but we can see how that was transformed by studying the Roll of Honour in Adulam Baptist chapel, Bon-y-maen (north Swansea).

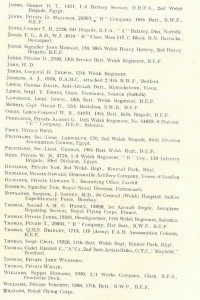

This Roll of Honour lists (as many chapel memorials do) all of those who served in the War, not just the fallen: in this case, 48 men. The number of names is not surprising: other Baptist chapels in the north Swansea area have 81 (Caersalem Newydd, Treboeth), 99 (Seion, Morriston) and 52 (Soar, Morriston). In 1914, Adulam had 231 members (a smaller membership than the other three chapel mentioned above) so one can be sure that the majority of young Adulam men who were eligible did join up.

This Roll of Honour is interesting and unusual in that its creator has signed it (T. Lewis of Morriston), with the date 1917. Therefore this was a ‘live’ document, added to as the war dragged on and more Adulam men were called up. One can see from the spacing at the bottom of the document that some of the names were squeezed in. Also, the names of battles were added to the pillars on either side, including a battle fought in 1918.

The design of this memorial is different to all those I have studied previously, though many of the features are familiar. The two red dragons in the top corners of the memorial is a feature seen in Penuel chapel, Loughor. The collection of Allied flags in the centre of the roll can also be seen in the Roll of Honour at Bethel, Llanelli. The pillars flanking the list of names are also a feature of the two memorials in Mynydd Bach chapel. One unexpected aspect I have never previously encountered is the image of Kitchener, just beneath the flags. It is indeed surprising to have a picture of a warrior like Kitchener, not known for his sympathy for the ideals of Welsh Nonconformity, in a Welsh chapel.

The wording of this memorial is also significant. ‘Rhestr yr Anrhydeddus’ (literally ‘List of the honourable ones’); ‘Aelodau’r Eglwys a’r Gynulleidfa sydd yn gwasanaethu eu Duw, eu Brenin a’u Gwlad’ (‘Members of the Church and the Congregation who are serving their God, their King and their Country’). Many Welsh chapel memorials will have wording that declares that the men fought for ‘Rhyddid’ (‘Freedom’) and ‘Anrhydedd’ (‘Honour’) but it is not common to have such an explicit declaration that they were fighting for ‘Duw’ (God’).

The key question which we must be careful in answering is whether we can infer from this memorial that the chapel accepted the argument that this was a just war. We cannot say for sure that the whole congregation was committed to fighting the war to the end, whatever the cost, but it is clear that the chapel’s leadership did adhere to the line that this was a war for right against might. I believe the fact that the memorial was commissioned in 1917 is significant: by then any illusions that people might have had early in the war that it would be over quickly had long since disappeared. Britain was not winning the war in 1917, but losing a constant stream of men in battles that did not appear to bring victory any closer. Yet this document still declares that the cause is just, for if God is on the Allies’ side, there can be no question about whether or not we are in the right.

Supporting evidence comes from the pages of the local newspapers, the Cambrian Daily Leader and the Herald of Wales. Searching the online database of the tremendous resource Cymru1914.org it is easy to come across reports of well over a dozen of the servicemen being honoured by the chapel when they returned home on leave, or were demobbed at the end of the war. (See, for example, the reports on Gwilym Leyshon and Willie Martin ).

Thus this single memorial contains a wealth of information that can help us understand how this community reacted to the war. The aim of the project is to share the details of a few hundred Welsh memorials, giving us the opportunity to examine how people and communities across Wales responded to the challenges of this unprecedented war, and thus a better idea of how the Welsh nation as a whole was scarred by the experience.

Dr Gethin Matthews, Swansea University

Meg Ryder February 15th, 2016

Posted In: iconography, memorials

Tags: chapels / capeli, iconography, Kitchener, memorials, Swansea, WW1

2 Comments

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.