Longing for Peace

A notable feature on the WW1 memorials in Wales was that they contained poetry as part of the inscription. Sometimes it is something written specially for the memorial by a local poet, as is the englyn on the memorial in the graveyard of Llwynyrhwrdd Congregational church near Tegryn, North Pembrokeshire

O sŵn corn ac adsain cad – huno maent.

Draw ymhell o’u mamwlad:

Gwlith calon ga glewion gwlad

Wedi’r cur, mwynder cariad.

[From the sound of the trumpet and the noise of battle – they sleep

far away from their motherland;

the brave of the land receive the dew of the heart,

after the hurt, the gentleness of love.]

This englyn is by John Brynach Davies, or “Brynach”, to use his bardic name. Brynach was a newspaper correspondent and an active member of this church, whose poetic compositions were numerous, competing in local eisteddfodau and celebrating local events. It was natural that he should contribute in this way and although his name is not on the memorial, there is no doubting that he was the author since the englyn appears in Awelon Oes, a compilation of his poetry published after his death in 1925 at a relatively young age. A note alongside the poem states ‘From the memorial stone to soldiers in Llwynyrhwrdd.’

At other time the inscription on the memorials will be a line from a poem by a well known poet, as is this quotation from a famous englyn by Ellis Evans, or ‘Hedd Wyn’, to use his bardic name. I have seen this line on memorial stones in the south-west in Aberbanc, Newcastle Emlyn and Pencader, and it would be interesting to know of other places where it is used as an inscription.

Eu haberth nid â heibio [Their sacrifice will not be passed by]

As Alan Llwyd and Elwyn Evans explain in their volume Gwaedd y Bechgyn: Blodeugerdd Barddas o Gerddi’r Rhyfel Mawr 1914-1918, he composed this englyn in 1916 in memory of Tommy Morris, a friend who died in France. Hedd Wyn was commemorating one person – the singular is used in the original poem , ‘his sacrifice’ – but memorials changed the singular to the plural, ‘their sacrifice’.

Ei aberth nid â heibio – ei wyneb

Annwyl nid â’n ango,

Er i’r Almaen ystaenio

Ei ddwrn dur yn ei waed o.

[His sacrifice will not be passed by –

his dear face will not be forgotten,

although Germany has stained

its steel fist in his blood.]

Sacrifice is not the only theme seen in these poems. Another is the memory of those who were lost will last for ever. One of the most popular quotations on this theme comes from the works of John Ceiriog Hughes, “Ceiriog”, which I have seen on 12 memorials in the south-west. .

Mewn angof ni chânt fod. [They shall not remain in oblivion.]

On two other memorials there is a slight variation of the same line.

Yn angof ni chânt fod. [They will not be forgotten.]

This quotation comes originally from a stanza in the poem Dyffryn Clwyd .

Mewn Anghof ni chânt fod,

Wŷr y cledd, hir eu clod,

Tra’r awel tros eu pennau chwŷth:

Y mae yng Nghymru fyrdd,

O feddau ar y ffyrdd,

Yn balmant hyd ba un y rhodia rhyddid byth!

[They shall not remain in oblivion,

men of the sword, much praised

while the wind blows over their heads:

there are in Wales a multitude

of graves along the ways,

a pavement on which freedom forever walks.]

Ceiriog died in 1887, without seeing the massacre of the First World War and is referring to heroes of a past age. But the use of this line on the inscription implies that the dead remembered there were themselves heroes who had earned their place in the same tradition of a deserved remembrance.

It’s not surprising to see poems such as these. They reinforce the theme of the memorial and are in keeping with the desire to remember the bravery and sacrifice of those lost. But occasionally a different kind of poem appears – a poem that rejects military values and longs for peace. So far I have only seen two such memorials, one on a memorial in Llanilar near Aberystwyth, and another on a memorial at Llangynog near Carmarthen.

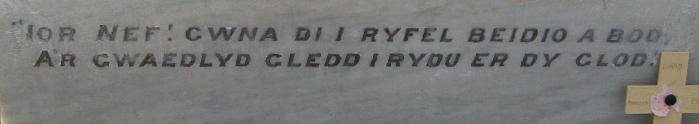

The wording on the Llanilar memorial in memory of one local man in a simple and fitting if one looks at the couplet which comes at the end of the inscription. I have been unable to find the name of the poet, but his feelings are quite clear. There is no war in a civilized world, and it is peace alone which praises God.

Ior Nef! Gwna di i ryfel beidio a bod,

A’r gwaedlyd gledd i rydu er dy glod.

[Lord of Heaven! Make war cease to be,

and let the bloody sword rust in your honour]

The inscription is entirely in Welsh and the feelings expressed publicly here, grieving the loss from the community of a young man and yearning to see an end to war, appear to be in agreement with the opinion of the community.

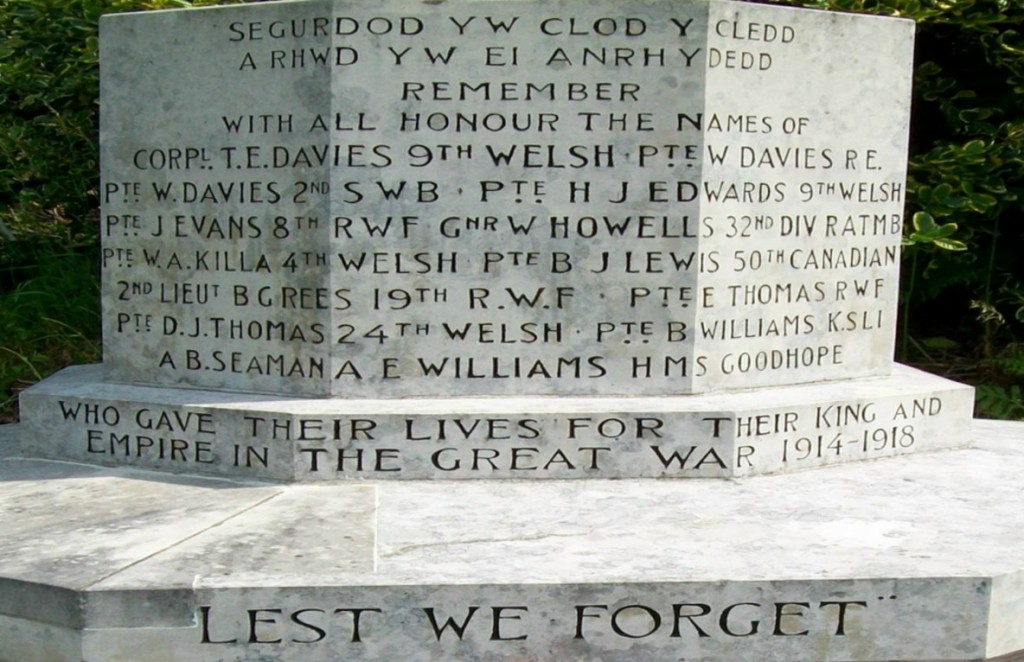

The situation in Llangynog is slightly different, although the poem quoted is similar in respect of conviction.  Here the inscription is in English and more warlike in its sentiment, with the soldiers who died having fought for their king and empire. But this is not the message proclaimed by the Welsh couplet on the memorial.

Here the inscription is in English and more warlike in its sentiment, with the soldiers who died having fought for their king and empire. But this is not the message proclaimed by the Welsh couplet on the memorial.

Segurdod yw clod y cledd,

A rhwd yw ei anrhydedd.

[Idleness is praise for the sword

and rust is its honour.]

This couplet comes from the famous englyn of William Ambrose, ‘Emrys’, which preaches uncompromising pacifism.

Celfyddyd o hyd mewn hedd – aed yn uwch

O dan nawdd tangnefedd;

Segurdod yw clod y cledd,

A rhwd yw ei anrhydedd.

[Skill always in peace – may it increase

under the patronage of peace;

Idleness is the praise for the sword

and rust is its honour.]

Did the people who framed the English wording with its military ostentation on the memorial understand the point of this quotation in Welsh? What happened in Llangynog that a memorial should be created which lauded war in one language but opposed it in the other?

Are there other examples of such poems on W.W.1 memorials in Wales which look forward to a future of civilized peace and an end to warring. And are there similar sentiments to be seen in English on memorials, either here in Wales or across the border? I’ve seen no such references, but it’s worth asking and searching.

Gwen Awbery

Cardiff

g.h.matthews June 3rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

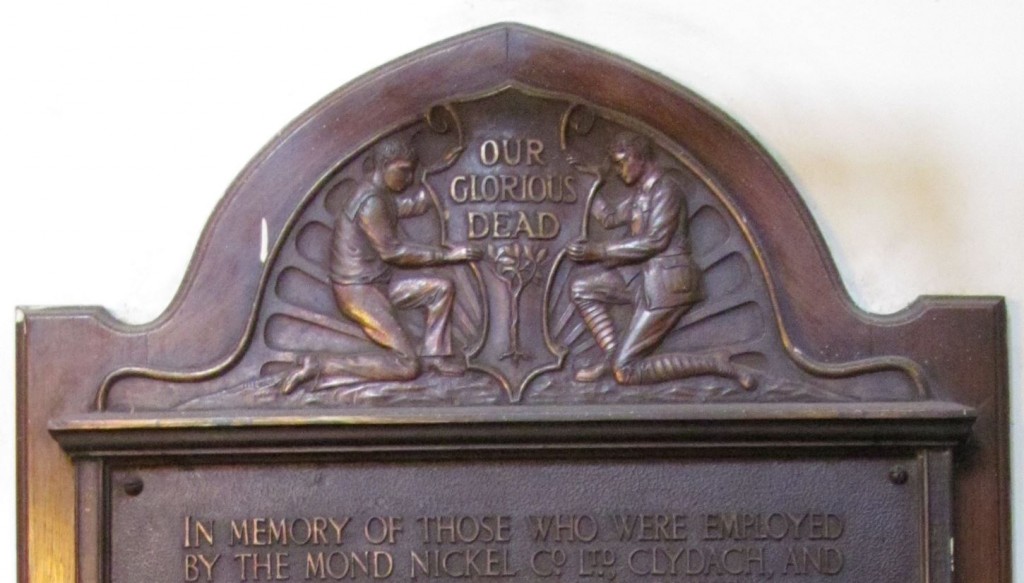

The Mond Nickelworks WW1 Memorial

For well over a century, the Mond nickelworks has been a major landmark and an important employer for the people of Clydach, in the lower Swansea valley. The works first produced nickel in 1902, using a process pioneered by a German chemist-entrepreneur named Ludwig Mond whose statue stands nearby, surveying his creation. Although the ownership of the works has changed over the decades, so that it is now operated by Vale, a Brazilian company, to locals it is simply ‘the Mond’.

On the way into the Mond Community Centre (attached to the works) you walk past two memorials, commemorating the 33 men associated with the company who died in the First World War, and the 19 who were killed in the Second World War.

The number of names on the WW1 memorial is striking, although it is only a fraction of the 450 Mond employees who volunteered or (after 1916) were conscripted into the armed services. The figures indicate that 250 employees (out of 850) volunteered to serve in the Armed Forces in the first few months of the war. Besides any other reasons for volunteering, they were encouraged and supported by the company’s management, who promised to pay half-wages to the families of married volunteers, and also to support the dependents of single men who joined up. Of course, the product of the Mond, refined nickel, was in high demand at wartime and it was a profitable time for the company. For more details of this, see this blog from 2014 on the BBC’s website.

One consequence of the flow of men from the Mond into uniform was that women were recruited to work in the manufacturing process for the first time: thus the list of names on the memorial is only part of the story of how the war affected the local community.

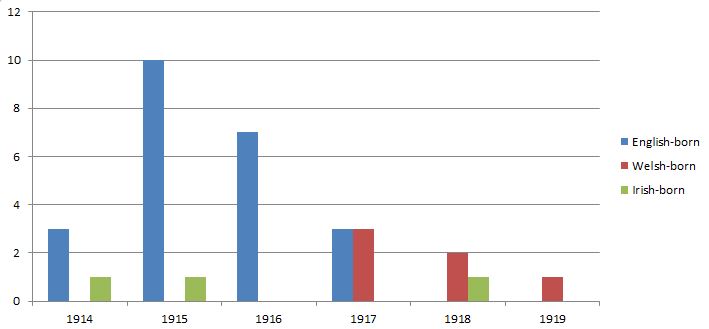

Excellent research work by local historian Bill Hyett into the details of the 33 men who died shows some interesting patterns that need to be carefully examined and explained.  Mr Hyett has found biographical and service details of all but one of the men. The statistic that stands out from this research is that over two thirds of them – 23 – were English-born. A further three were Irish-born, meaning that only six were Welsh-born. This does not reflect the general workforce at the Mond, where the majority of the names on the employment register are clearly Welsh.

Mr Hyett has found biographical and service details of all but one of the men. The statistic that stands out from this research is that over two thirds of them – 23 – were English-born. A further three were Irish-born, meaning that only six were Welsh-born. This does not reflect the general workforce at the Mond, where the majority of the names on the employment register are clearly Welsh.

A clue to explain this discrepancy can be found when studying the patterns of when these servicemen were killed. Of the four who died in 1914,three were English and one Irish; in 1915, ten English and one Irish were killed; all of the seven casualties in 1916 were English-born. Then in 1917 three English-born and three Welsh-born died; in 1918 two Welsh and one Irish and the final casualty, who died in 1919, was Welsh.

This demonstrates that most of those who joined up earliest in the war, and who were thus most likely to be killed in it, were English-born. Most of these had lower-paid unskilled jobs at the plant, and some had not been working there very long. One example is Reginald Edwards, born at Erdsley, Hereford. His employment at the Mond was very brief, as he started work on 11 August 1914 and volunteered for the Royal Field Artillery in September 1914. Thus those who were most likely to join up early in the war were the unskilled labourers, many of whom had moved to Clydach from England. The local-born workers often had better-paid, higher-skilled jobs, and so were less likely to volunteer for the armed forces.

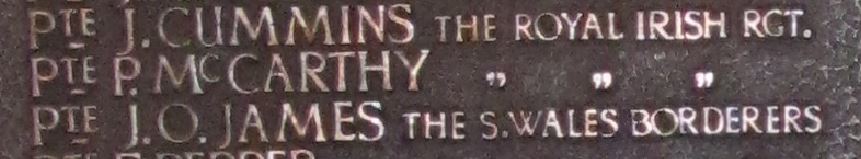

Here are details from Mr Hyett’s magnificent research of two individuals which give an idea of the human stories behind the list of names on the metal plaque. The first of the Mond casualties was Tipperary-born Peter McCarthy, who was about 25 years old when he began work at the Mond in March 1914. He must have been an army reservist, called up in August 1914, for he was killed on the Western Front on 7 October 1914: he has no known grave.

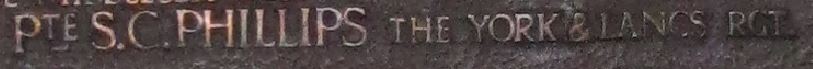

The final Mond casualty was Sidney Phillips (noted on the memorial as S. C. Phillips, though Mr Hyett’s research has shown that his middle name was George). He was Swansea-born and lived in Ebenezer Street, Swansea with his wife and three children. Sidney was one of those who volunteered in 1914, initially serving with the Welsh Regiment before transferring to the York and Lancs Regiment. He suffered a gun-shot wound to the thigh in May 1916 but recovered, only to fall victim to a gas attack in France. He was invalided home and discharged from the army in September 1918, but died on 17 April 1919 and received a military funeral in Swansea’s Dan-y-Graig cemetery.

g.h.matthews May 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Patterns of Memorialisation

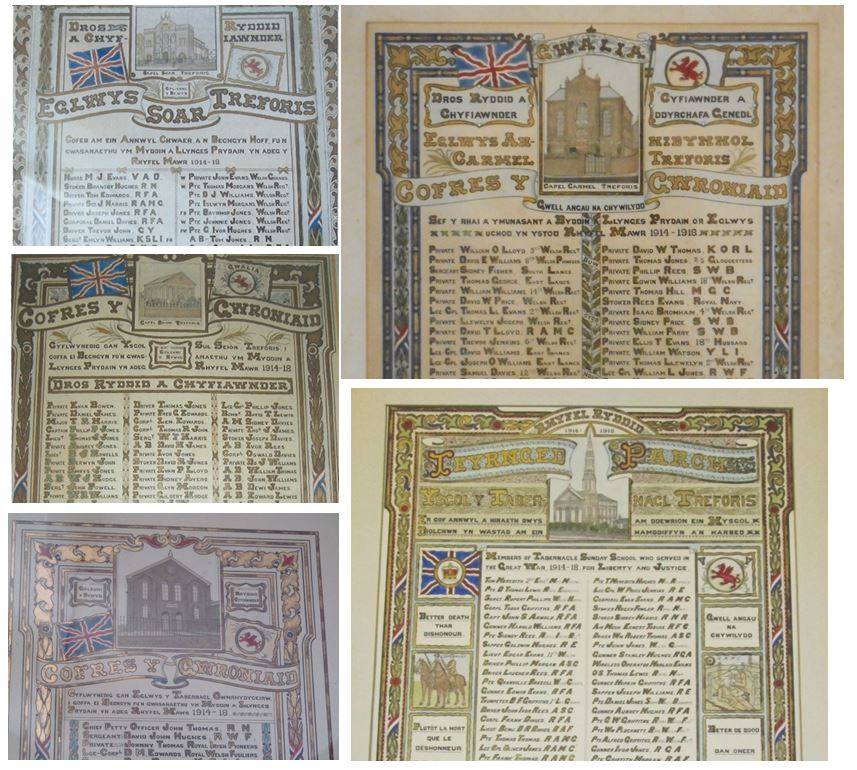

One of the patterns that has become clear as we gather material from around Wales for the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project is that patterns of memorialisation can be local. That is, particular communities in certain areas will have the same kinds of memorials to those who served in the First World War.

One example can be seen in the nonconformist chapels of Morriston. Another blog post looks at these in more detail – look at how similar the various chapel memorials are.

These five memorials have all been designed by the same man, and they all have an image of the chapel building to the fore, flanked by the Union flag and the Welsh dragon.

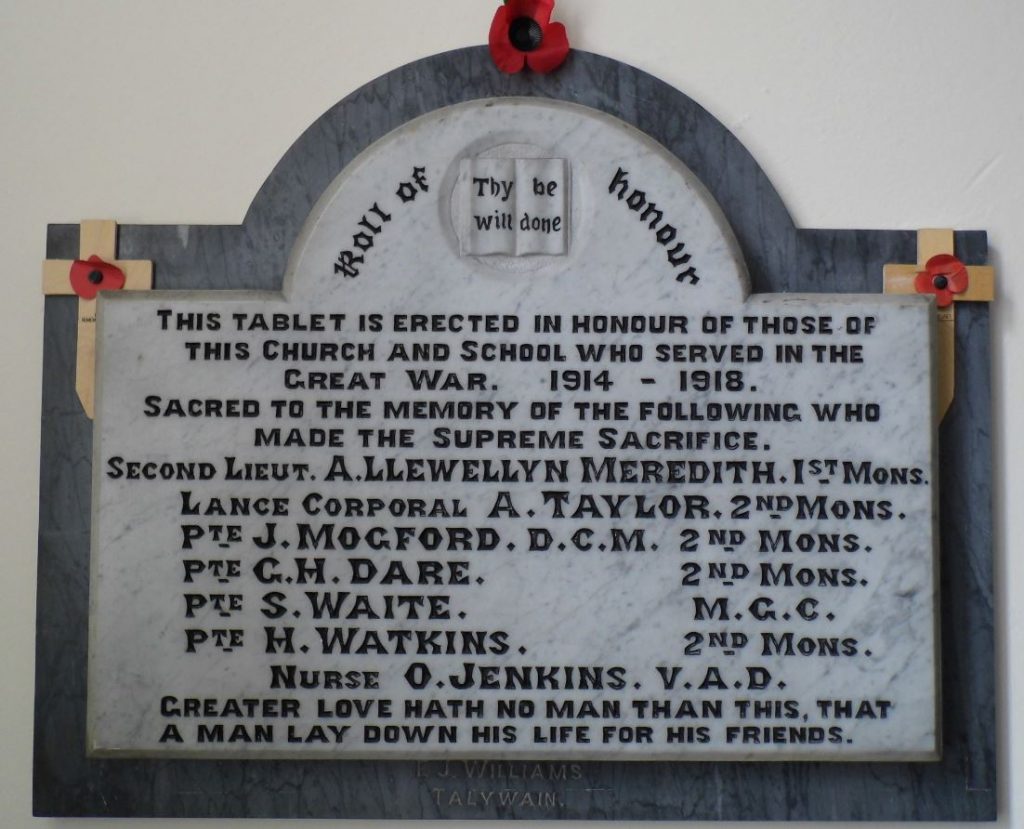

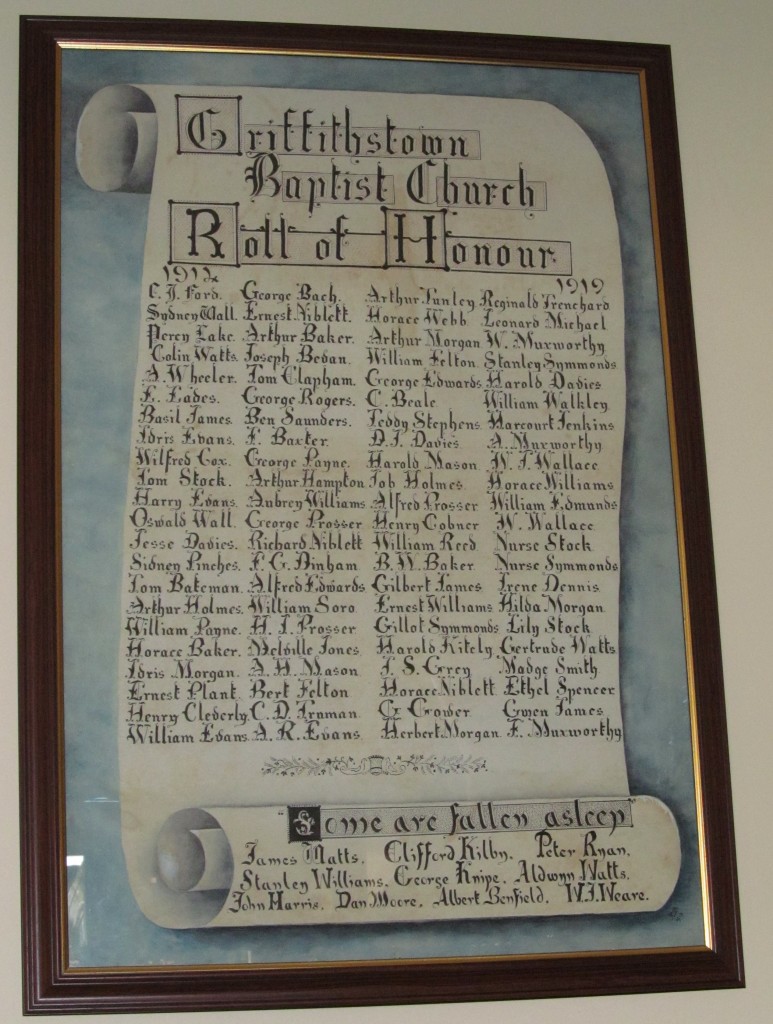

Another patch of Wales where a number of interesting chapel memorials have survived is the Pontypool area. Below are five examples of memorials from Baptist chapels in the area which, although different in design, share some important features.

The memorial in Ebenezer Baptist chapel, Griffithstown (south of Pontypool), was designed by Mrs K. Davies, the minister’s wife, and was unveiled in March 1919. It lists the names of 78 men and then ten women who served, and then names the ten men who died on active service. (The final woman on the list is F. Muxworthy: this is almost certainly Frances Muxworthy of Kemeys Street, Griffithstown, who served with Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. This also suggests that two of the men listed are her brothers, Arthur and William Muxworthy).

In Merchant’s Hill Baptist chapel, Pontynewynydd, a Roll of Honour was unveiled in  October 1919, naming five men who died, and 47 men and one woman who served.

October 1919, naming five men who died, and 47 men and one woman who served.

There is also in this chapel a memorial which names six men and one woman who died.

Moving north of Pontypool to Talywain, there is Pisgah chapel. Here the memorial is in marble, and it lists three men who were killed in action, and then gives the names of 44 men and four women who served.

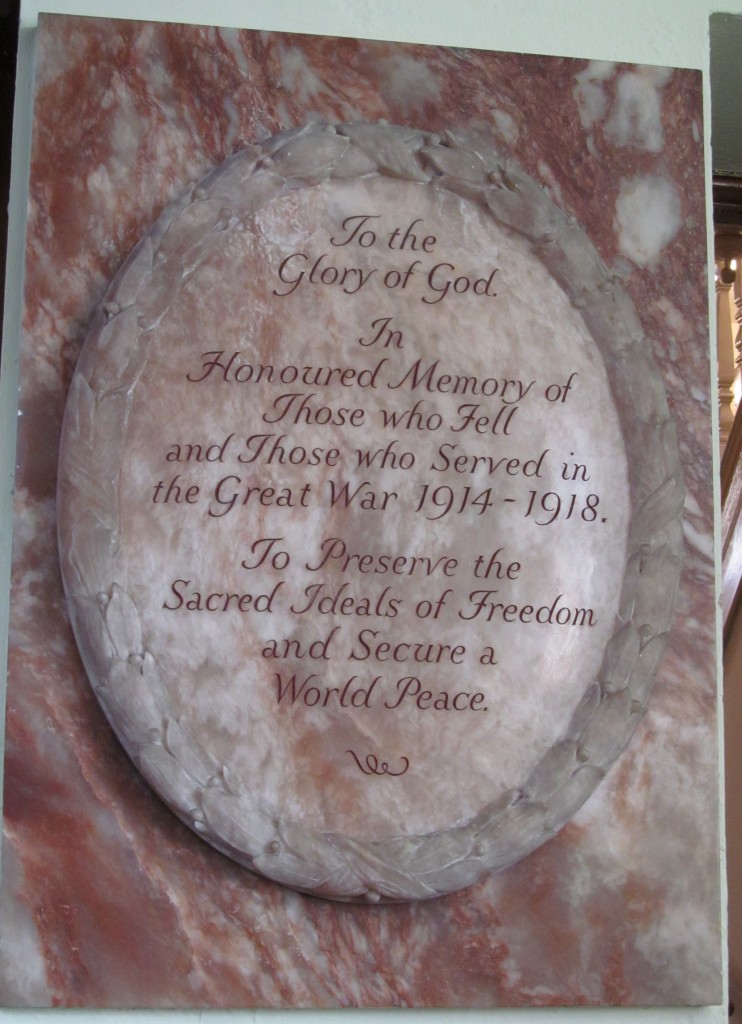

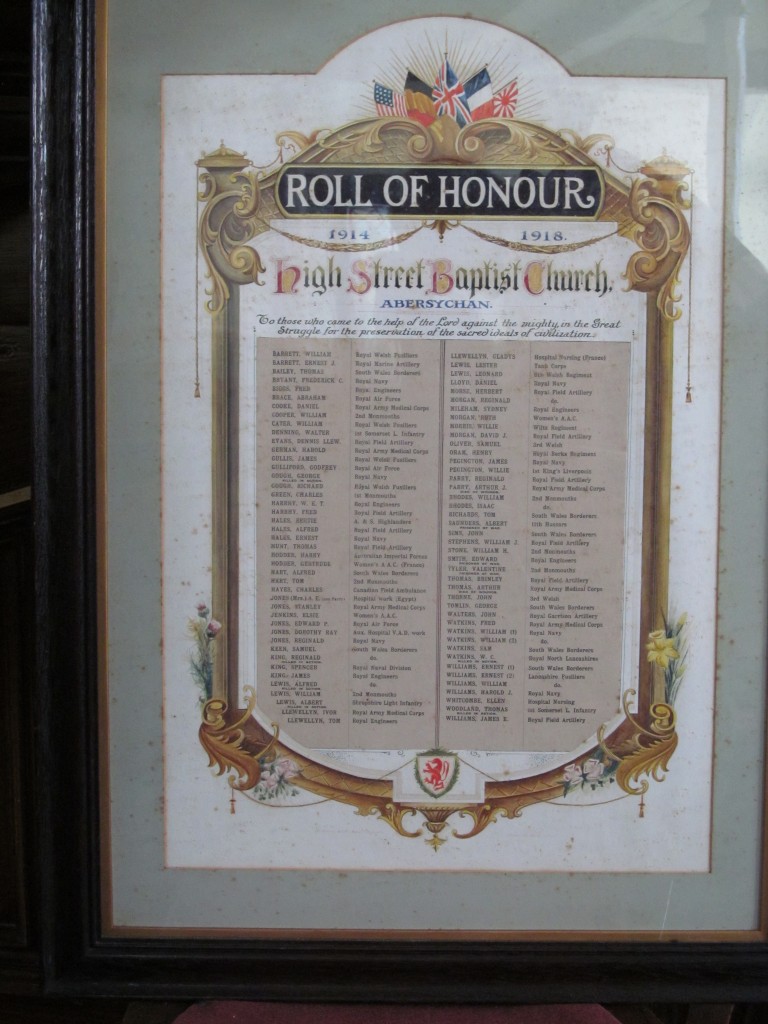

Just down the road in Abersychan there is the High Street English Baptist chapel.

The list here is alphabetical (unlike the list in the others mentioned here) and it contains 85 names, including seven women. Eight of the men were killed in the war.

On prominent display in the chapel there is also a marble tablet celebrating the peace that came at the war’s end.

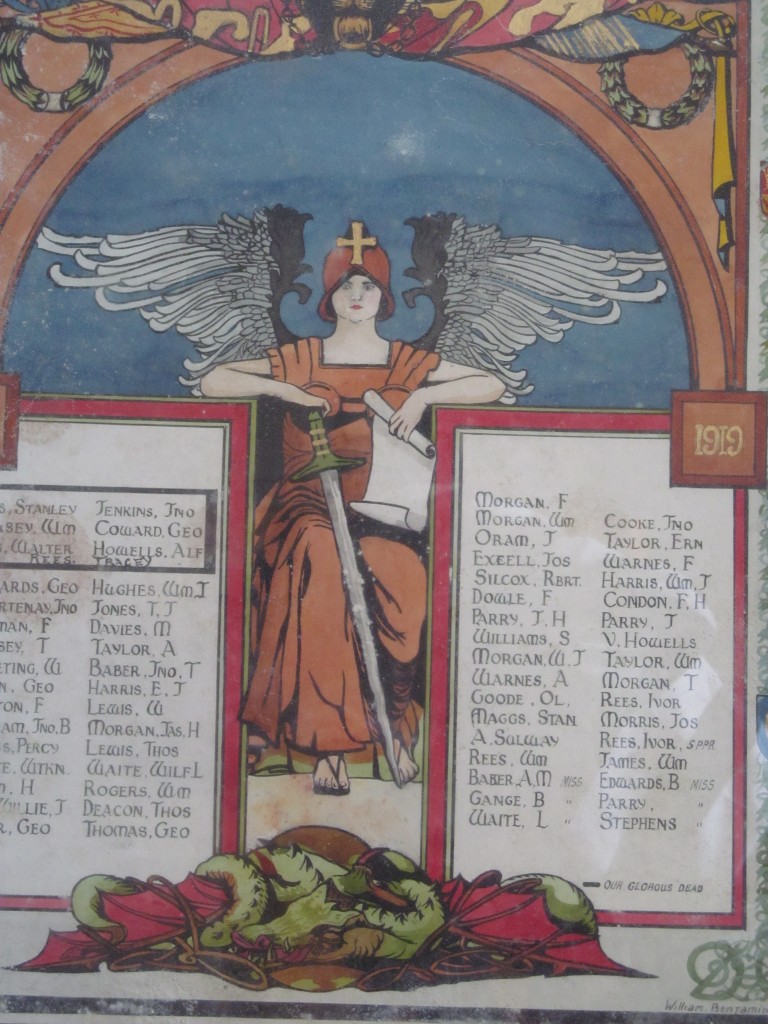

A stone’s throw away from High Street chapel is Noddfa, yet another Baptist chapel. The memorial here lists seven men who died and then the names of 53 other men who served and six women.

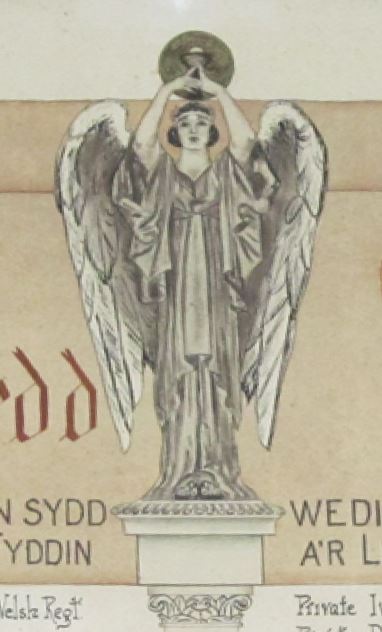

In visual terms, this is obviously the most striking of the five. The memorial, designed by William Benjamin John of Abertillery, has some very strong symbolism. The central figure is an angel; above is a lion with chains in its mouth; at the bottom is a slain dragon. This is probably the most vivid image of a chapel memorial so far collected by the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project.

Having noted the differences in the appearance of the four memorials described, it is also worth dwelling on their similarities. All of these memorials honour those who served, as well as mourning those who died. (Around a half of the Welsh chapel memorials so far gathered are Rolls of Honour which list all who served). All of these memorials name the women who served (mainly as nurses, but also in units such as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) – whereas in general only around a third at most of Welsh chapel Rolls of Honour include the names of women.

Perhaps there is a case of imitation here, or maybe we could even say competition. The chapels were proud of their communities’ contribution to the war effort and they wanted to demonstrate it. Thus as well as the clear motivation of honouring those who served in the war, there was also an element of pride in both the execution of the memorial and in the length of the list of chapel members who had ‘done their duty’.

g.h.matthews May 9th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

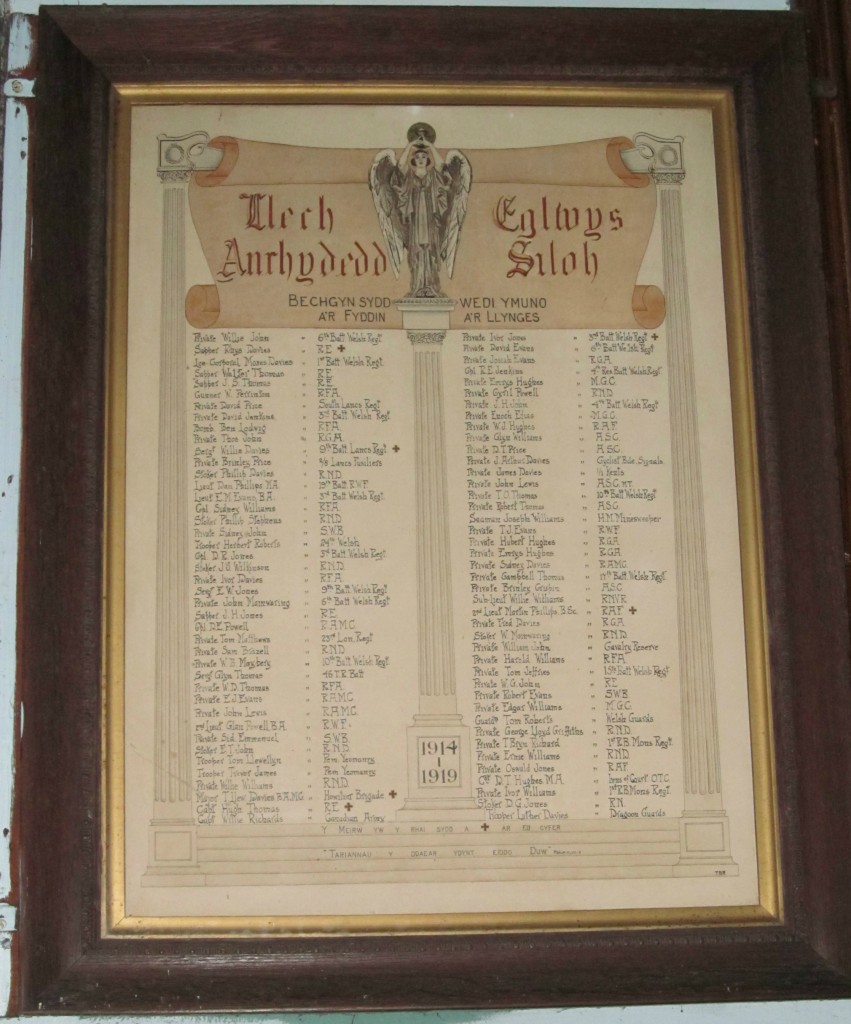

The Shields of the Earth: the WW1 memorial in Siloh, Landore

After almost 190 years, the grand Independent chapel of Siloh, in the Landore area of Swansea, closed its doors in January 2016. A hundred years ago the membership stood at around 640; at the end of the Second World War, there were over 600; when the chapel closed, the number of members was in single figures.

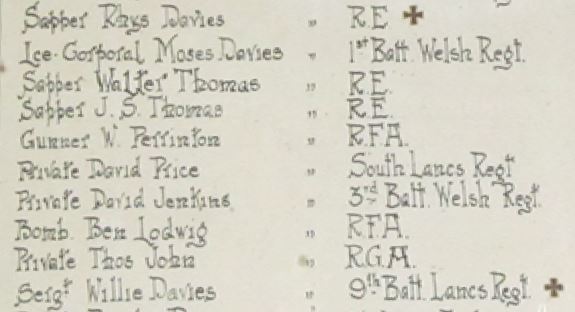

In the building’s vestry there was a roll of honour to remember the 84 men of the chapel who served in the armed forces between 1914 and 1918. This figure is not unusal for a chapel memorial in north Swansea – there are, for example, 81 names on the memorial at Caersalem Newydd, Treboeth, and 66 on the memorial at Carmel, Morriston.

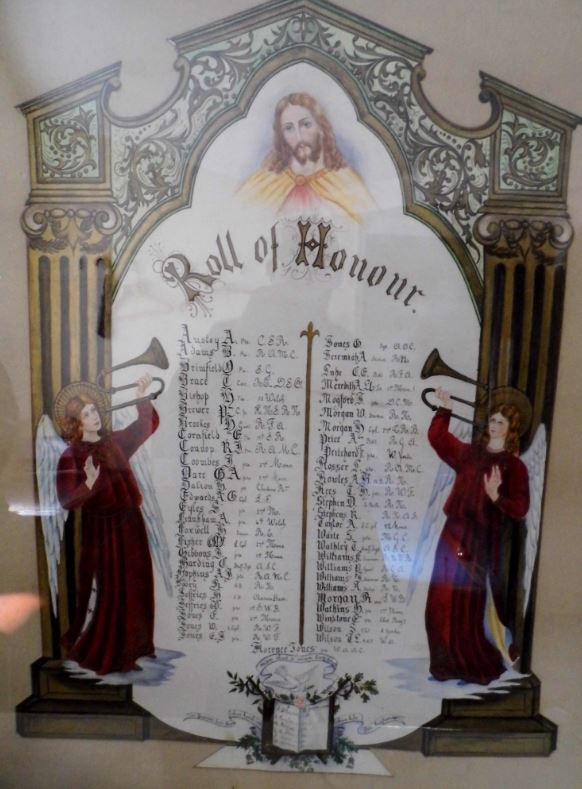

The imagery on this memorial is interesting, but again it is similar to other examples.  Classical-style pillars can be found flanking the names in the memorials of chapels such as Mynydd Bach (north Swansea), Zoar (Merthyr), Graig (Merthyr), Libanus (Dowlais) and Carmel (Aberdare), to name just five. Similarly, angels adorn the memorials in Zoar (Merthyr), and Noddfa, Abersychan.

Classical-style pillars can be found flanking the names in the memorials of chapels such as Mynydd Bach (north Swansea), Zoar (Merthyr), Graig (Merthyr), Libanus (Dowlais) and Carmel (Aberdare), to name just five. Similarly, angels adorn the memorials in Zoar (Merthyr), and Noddfa, Abersychan.

The Biblical verse (Psalm 47:9) is not one of the common choices: ‘Tariannau y ddaear ydynt eiddo Duw’ (‘the shields of the earth belong unto God’ in the King James version) although similar sentiments can be found on chapel memorials all over Wales.

While looking at the servicemen listed, we know (thanks to the chapel’s annual reports) that 18 volunteered in 1914 and 10 in 1915. Conscription was introduced in early 1916 so we cannot tell how much choice the 25 who joined up that year had, nor the 15 in 1917 nor the 12 in 1918.

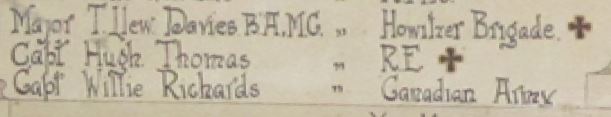

One of the men (Captain Willie Richards) served with the Canadian forces: again, there are plenty of similar examples across Wales of men who served with (in particular) the Canadian or Australian forces. This reflects the substantial emigration that had taken place from Wales to the dominions in the decade up to 1914.

One of the men (Captain Willie Richards) served with the Canadian forces: again, there are plenty of similar examples across Wales of men who served with (in particular) the Canadian or Australian forces. This reflects the substantial emigration that had taken place from Wales to the dominions in the decade up to 1914.

It is not just this ‘llech anrhydedd’ (literally ‘slate of honour’) that indicates the chapel’s viewpoint on the justice of the British cause. Letters were sent every Christmas by the minister, the Rev. Samuel Williams, to the soldiers and sailors of his flock, assuring them that Siloh supported them and prayed for them. When the men returned home on leave, the chapel organised meetings to welcome them: you can read here a report from January 1917 of a meeting when Private Tom Matthews was presented with a fountain pen by the Rev. Williams.

Unlike many other chapel memorials, the names of those who were killed are not listed separately, nor on another memorial, but a cross was added by the names of six men to show that they died in the war.

Unlike many other chapel memorials, the names of those who were killed are not listed separately, nor on another memorial, but a cross was added by the names of six men to show that they died in the war.

Although Siloh has closed its doors as a place of worship for the last time and the building is to be sold, the future of this memorial is secure, as it has been transferred to the care of West Glamorgan Archives.

g.h.matthews April 25th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

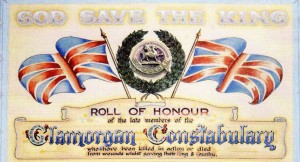

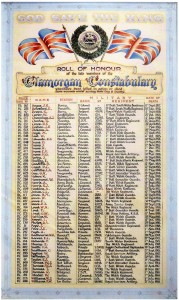

The Glamorgan Constabulary Roll of Honour

The ‘Welsh Memorials to the Great War’ project is interested in those memorials which commemorate the service of members of particular communities, be they chapels, clubs, schools or workplaces. Of course, many of these institutions have disappeared or been transformed over the intervening years. In terms of workplaces it is very difficult to find mines or industrial manufactories that are still going concerns.

One institution that still has its place in society is the police force. Here there have been re-organisations, so that the old Glamorgan Constabulary has merged with the formerly independent police forces of Cardiff, Merthyr, Neath and Swansea to form the South Wales Police. The urban police forces have their own memorials to policemen who fell while serving in the First World War, but the focus of this article is the Glamorgan Constabulary.

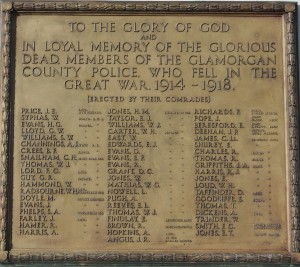

Outside Police HQ  in Bridgend there stands an impressive memorial to the fallen, listing the 58 who were killed in WW1 and 28 who were killed in WW2.

in Bridgend there stands an impressive memorial to the fallen, listing the 58 who were killed in WW1 and 28 who were killed in WW2.

Usually, a striking WW1 Roll of Honour is on display inside the building –  but while some refurbishment is being completed this memorial is currently in the Cardiff station.

but while some refurbishment is being completed this memorial is currently in the Cardiff station.

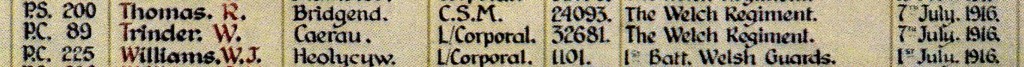

This impressive memorial lists the 58 names and gives further details of their police service.

The South Wales Police First World War Project Group has been active in researching these men so that it become more than a mere list of names. A series of booklets are being produced, starting off with one which tells the story of those who fell in 1914.

Looking at the booklet about 1915, it is remarkable that five Glamorgan policemen and one Cardiff constable were killed on one day, 27 September 1915, the first day of the Battle of Loos (in Belgium, on the Western Front). Five more south Wales policemen died within a month in that vicinity.

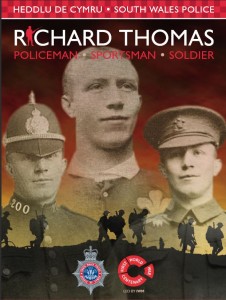

Another booklet tells of the connections between the police forces of South Wales and the Welsh Guards, and one further booklet focusses in on the story of Richard Thomas (known as Dick).

Born in Ferndale in 1881, he was a very well-known sportsman before the war, being capped as a forward four times for Wales between 1906 and 1909. He was part of the Wales team that won the Grand Slam for the first time, when they beat Ireland in March 1908. Although his reputation was as a hard-tackling forward, he occasionally also played as a back for the Glamorgan Police side. To show that he was a real all-rounder, he was also the Glamorgan Police heavyweight boxing champion on three occasions.

In August 1913 Dick was promoted to sergeant and was stationed at Bridgend. However, five months into the War he volunteered for the 16th Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, known as the Cardiff City Battalion. This was part of the ‘Welsh Army Corps’ – raised as part of the recruitment drive headed by Lloyd George with the aim of putting ‘a Welsh army in the field’. After training in Wales, the unit headed off for further training in Winchester before departing for the Western Front as part of the 38th (Welsh) Division.

The division was involved in a major battle for the first time at Mametz Wood, six days into the 1916 Somme campaign. The Cardiff City Battalion were among those ordered to make an assault across open ground to capture the heavily defended wood on 7 July. Dick Thomas was one of the battalion’s 300 casualties that day.

Looking at the Glamorgan Constabulary memorial, you will see details of some others killed in the same battle. Robert Harris (Cardiff City Btn, 7 July 1916), William Edward Trinder (Cardiff City Btn, 7 July 1916) and William Henry Loud (10th (1st Rhondda) Btn, Welsh Regiment, 10 July 1916) were killed as the Welsh took Mametz Wood; Edward Beresford (South Staffordshire Regt, 10 July) was killed nearby in a supporting action.

With thanks to Gareth Madge for his assistance

g.h.matthews April 18th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

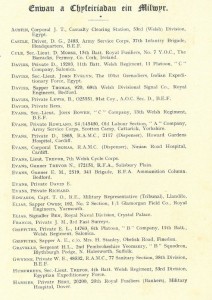

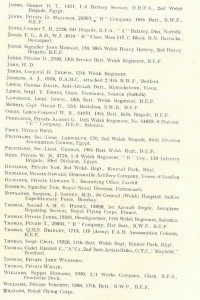

WW1 Memorial in Y Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel in Cardiff

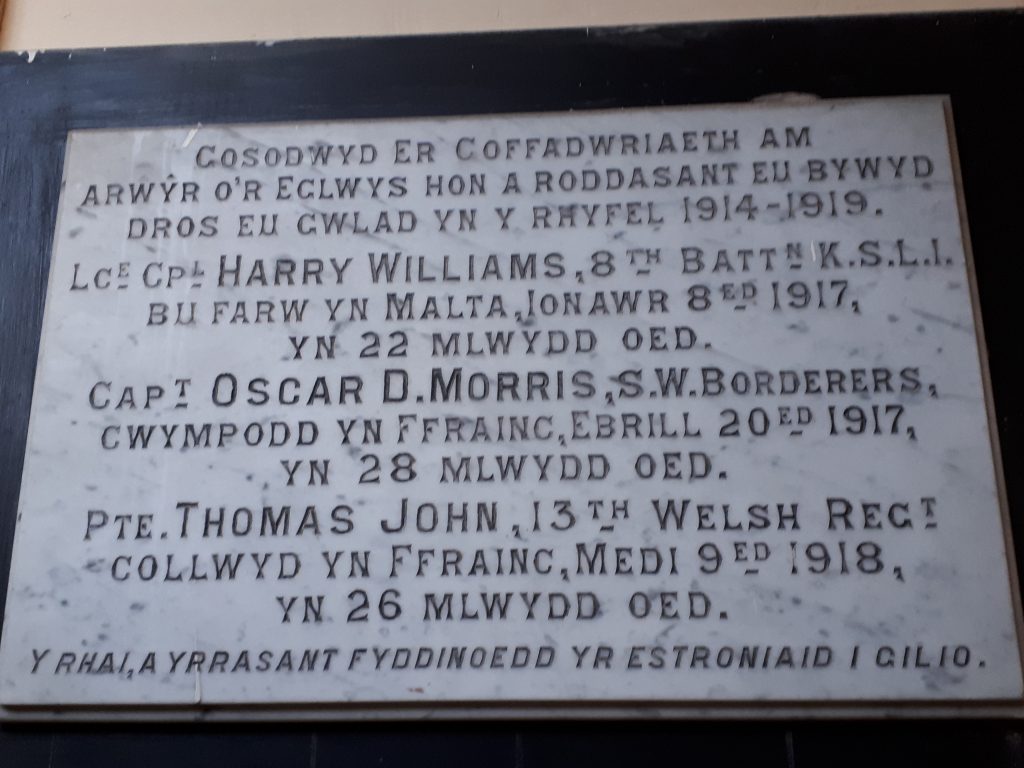

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

On a wall inside the Tabernacl, the Welsh Baptist chapel on the Hayes in central Cardiff, there is a memorial to the six men of the congregation who died in the Great War.

The memorial itself is impressive, being carved in marble.

There are no records to indicate whether the chapel displayed a ‘Roll of Honour’ as the war was being fought, to highlight the contribution of a large number of the congregation to the war effort. However, the chapel’s Annual Reports do note the names of all the men who enlisted, and so we can trace how the war had a deeper effect every year on the congregation. There were 45 names on the list at the end of 1915, 62 by the end of 1916 and 66 in 1917 (including four who had been killed). The membership of the Tabernacl during the war fluctuated from around 520 to 560, so the total of 66 represents a sizeable proportion of the young male membership of the church.

List of chapel members serving in 1916

We can also see how the War’s impact became deeper and more painful from the minister’s comments in the reports. At the end of 1914 there was more discussion about the fire that had damaged the chapel than about the War, but the Rev Charles Davies’ comments became ever more emotional as the war dragged on and took an ever-increasing number of young men from his flock. Looking back upon 1916, he wrote that the young men left a large gap, and that their valuable contribution to the life of the chapel was deeply missed by those who were left. However, there is no doubt that the minister considered the war to be just, as he used such words as ‘teyrngarwch’ (loyalty), ‘dewrder’ (courage) and ‘aberth’ (sacrifice) to describe the men’s contribution to the war effort. He declared that as they faced the dangers and discomforts of the war, they were fighting ‘er amddiffyn ein gwlad, a sicrhau buddugoliaeth i gyfiawnder a gwir rhyddid yn ein byd’ (to defend our country, and to ensure a victory for justice and for the true freedom of our world).

In the lists of the men there is information about where a number of them were serving. At the end of 1916 a large number were in training camps in England or Wales; 14 with the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) on the Western Front; six in Egypt; four in Salonica and one in Bombay.

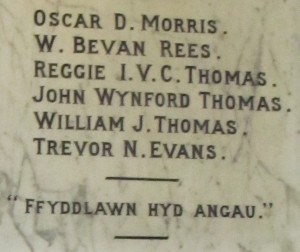

The first name on the memorial is Oscar D. Morris. It is possible to find a great deal of information about him: the letter he wrote as he sought to join the Welsh Army Corps are available on the Cymru1914 website – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/archive/4089505

One can also find a report on his promotion to lieutenant (August 1915 – http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886208/7/ART121) and then reports on his death on the Western Front on 21 April 1917 (http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886989/1/ART11 and http://cymru1914.org/en/view/newspaper/3886999/3/ART35 ).

Oscar’s name is also to be found on the memorial in his home chapel – Salem Nantyffyllon.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

The second name is W. Bevan Rees, originally from Llandybïe, Carmarthenshire (who was 20 years old and working as a miner at the time of the 1911 census). He died in Palestine on 3 November 1917.

Reggie I.V.C.Thomas is the next name: he died on 24 November 1917 aged 19, while serving on the Western Front with the South Wales Borderers. He has no known grave, but his name is on the Cambrai memorial.

One can find John Wynford Thomas as a 12 year old boy in the 1911 Census, living in Lampeter Velfrey. There is no indication of when he moved to Cardiff, but he enlisted in the city, joining the South Wales Borderers. He was killed in Flanders on 31 October 1917.

Despite his common name, it is certain that the William John Thomas named on the memorial was an 18 year old who died on 11 July 1918 while serving with the Army Service Corps. He is buried in Cathays Cemetery, Cardiff.

However, the final name on the memorial is not on the list of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. According to the Tabernacl’s records he was a soldier in 1916, serving as a Gunner with the RFA (Royal Field Artillery) on Salisbury Plain. The chapel’s report says that he died on 18 February 1919.

g.h.matthews March 22nd, 2016

Posted In: chapels / capeli, memorials, Uncategorized

Tags: chapels / capeli, memorials, WW1