WW1 memorials in Morriston’s chapels

As the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project has gathered information about WW1 memorials from all over Wales, it has become clear that different parts of Wales can have different patterns of memorialisation. One clear generalisation is that industrial Wales had a greater number and variety of WW1 memorials than rural Wales. Although there are plenty of interesting exceptions, as a rule the WW1 memorials in rural Wales are thinner on the ground and have fewer names commemorated on them – which is obviously related to the sparser population in these areas.

Within industrial or urban Wales, there are also some interesting patterns: some areas where memorialisation was more intense than others. (Of course, one factor to bear in mind is the survival rate of memorials may not be uniform, and there are some parts of Wales where it appears that more have been lost than have survived). This article will focus in on Morriston, north Swansea, an area which had a very strong concentration of Nonconformist chapels in 1914.

The map above gives an idea of the distribution of these chapels (using the data of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales). Some of these chapels have closed down, while others have merged, but a fair number of their memorials are still extant.

The map above gives an idea of the distribution of these chapels (using the data of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales). Some of these chapels have closed down, while others have merged, but a fair number of their memorials are still extant.

As a result of there being so many chapels in one locality, there was an element of rivalry between them, and we can see that expressed during the period 1914-18 in terms of the question of how many recruits had joined from each congregation. Each institution sought to show that it was ‘doing its bit’ for the war effort, and so publicised the number of their young men who had joined the Armed Forces. For example, a newspaper report in 1916 declared that ‘Carmel Church is not one of the largest in Morriston, but has the good record of having 36 of its members and adherents with the Colours’ (Herald of Wales, 22 January 1916, p.8).

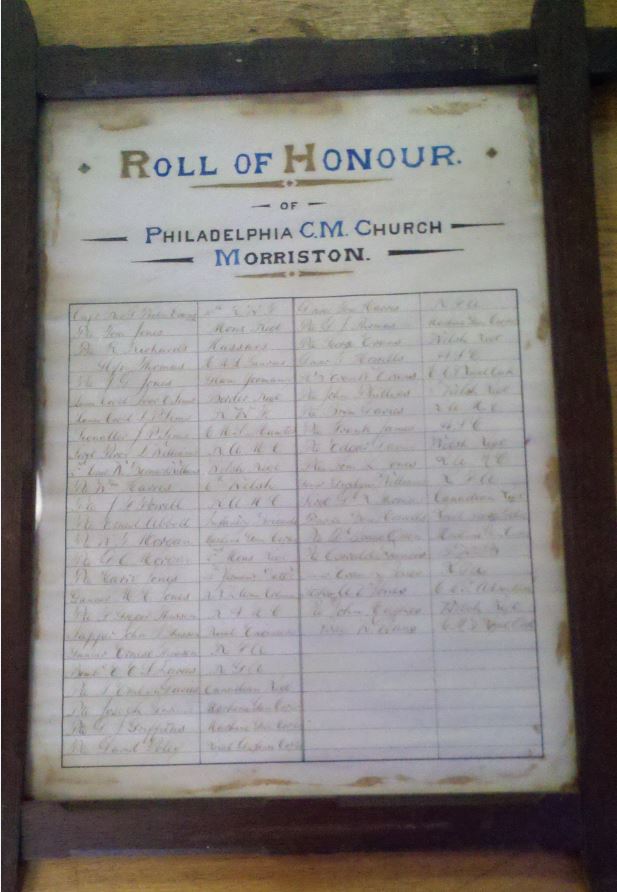

Here is an example of a contemporary Roll of Honour that was kept by Philadephia (Calvinistic Methodist) chapel, Morriston. It is likely that most local chapels had Rolls of Honour similar to this one on display as the war was being fought.

However, most of these have not survived, as they were superseded by more ornate memorials commissioned at the end of the war.

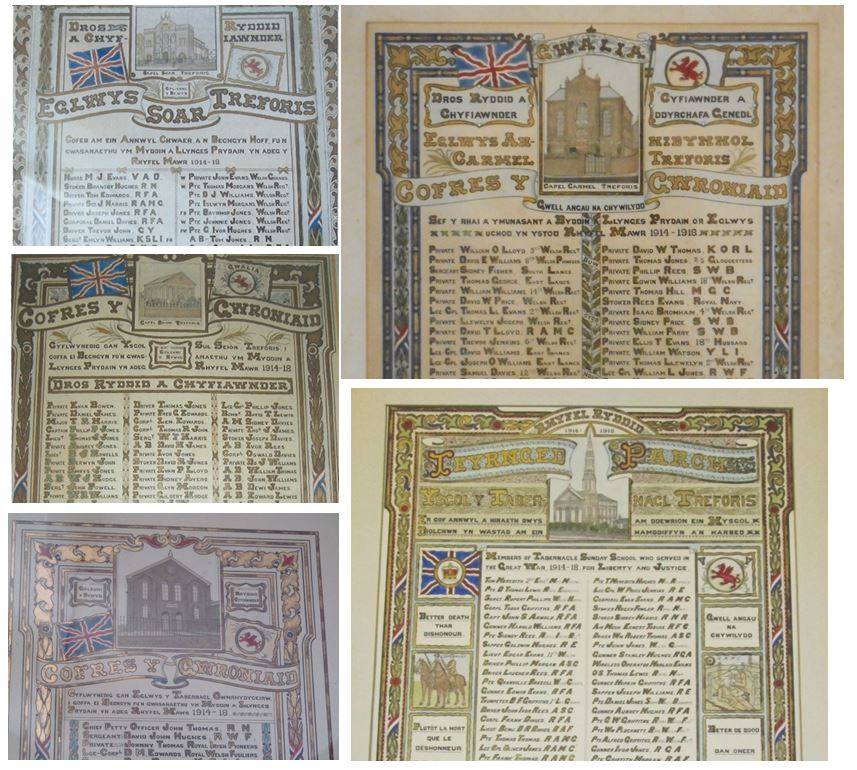

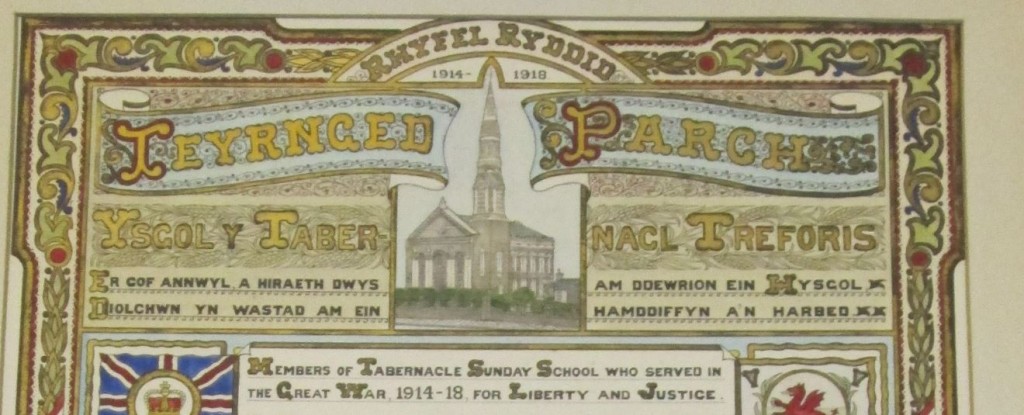

One thing that is clear from looking at the memorials below is that one local artist designed a number of them. W.J.James, of Penrhiwforgan, Morriston, designed all of the ones below: clockwise from the top-left – Soar; Carmel; Tabernacl; Tabernacl, Cwmrhydyceirw and Seion. In each of these designs there is an image of the chapel building in the middle towards the top, flanked by the Union flag and the Welsh dragon.

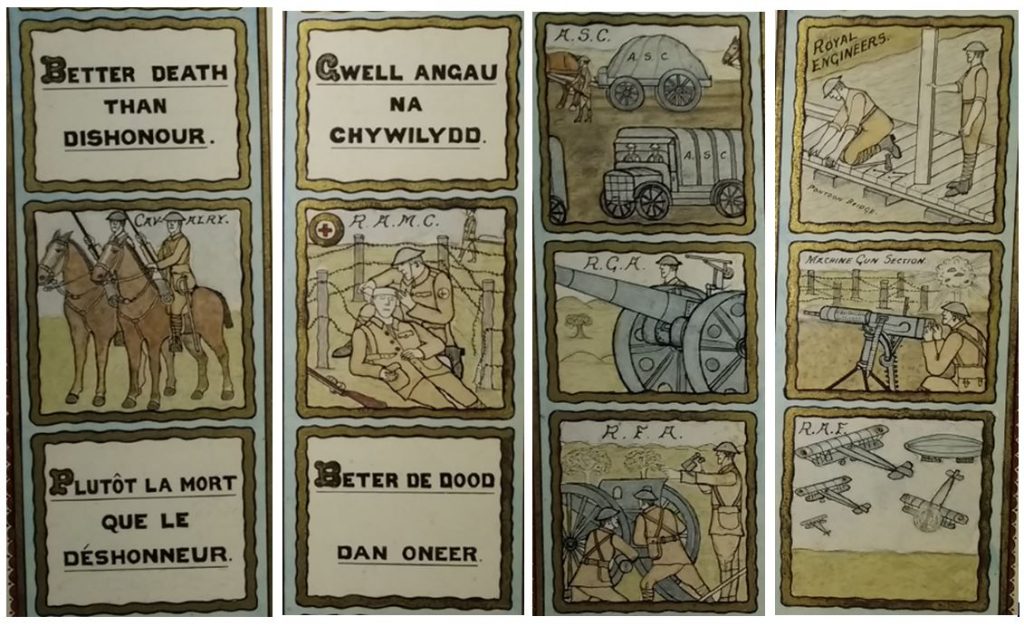

The design of the memorial of Tabernacl (on Woodfield Street – renowned as one of the most grandiose of all the chapels in Wales) is particularly interesting. It has the motto of the Welsh Regiment, “Better death than dishonour” in four languages (English, Welsh, French and Flemish) and ten militaristic pictures, including images of machine gunners and tanks.

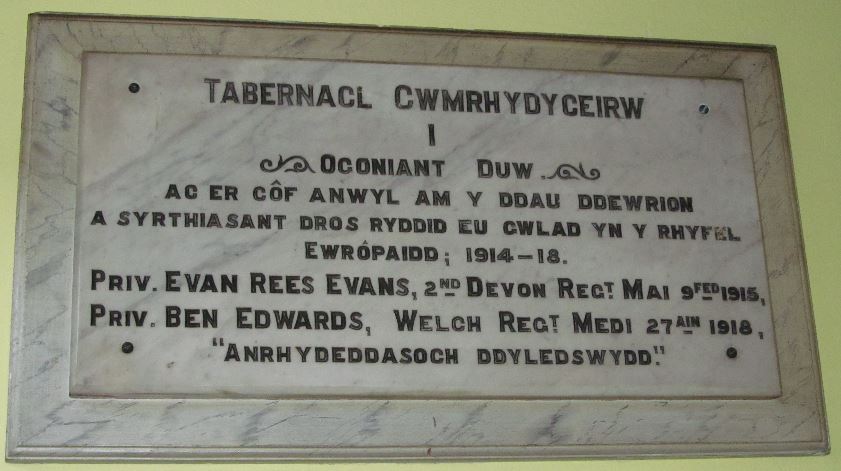

As well as the Roll of Honour, Tabernacl (Baptist) Cwmrhydyceirw has a tablet commemorating the two men from the chapel who died.

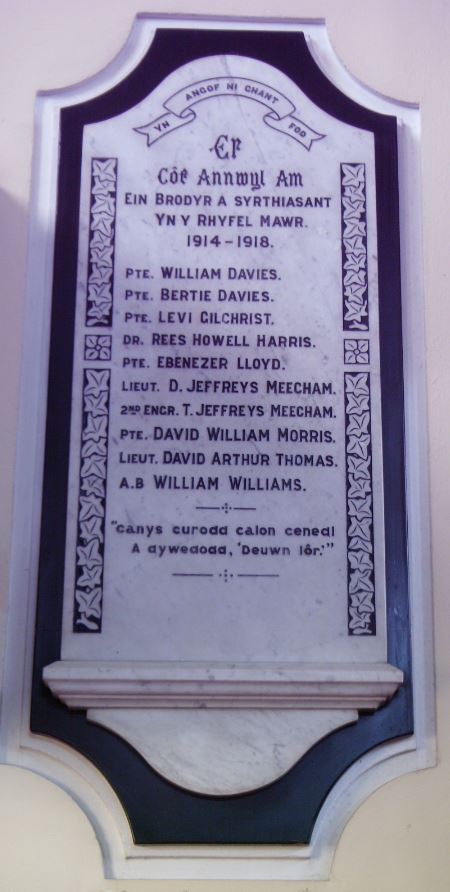

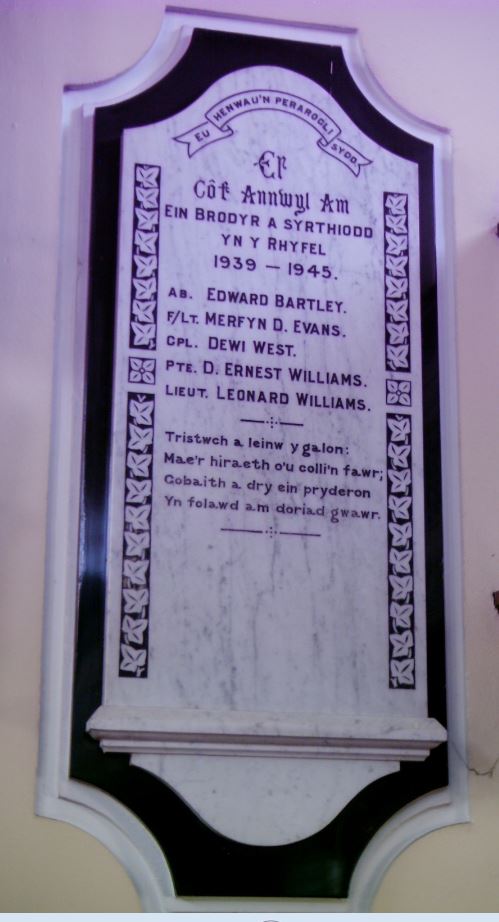

Bethania (Calvinistic Methodist) does not have a Roll of Honour – although the Annual Report for 1919 does give details of the 55 men from the chapel who served in the war. It has, on one side of the pulpit, a marble memorial to the 10 men from the chapel who died. It also has, on the other side, a similar memorial to the 5 men who were killed in the Second World War, as sad testimony to the fact that the Great War was not, after all, ‘the war to end wars’.

g.h.matthews February 5th, 2018

Posted In: Uncategorized

Joining the Dots – Part 2

In a previous blog post we noted a few instances where individuals were commemorated on more than one memorial. This is to be expected if a man (or woman) had a connection with a number of institutions that felt the need, either as the war was being fought or at its end, to remember those who had served, and those who died.

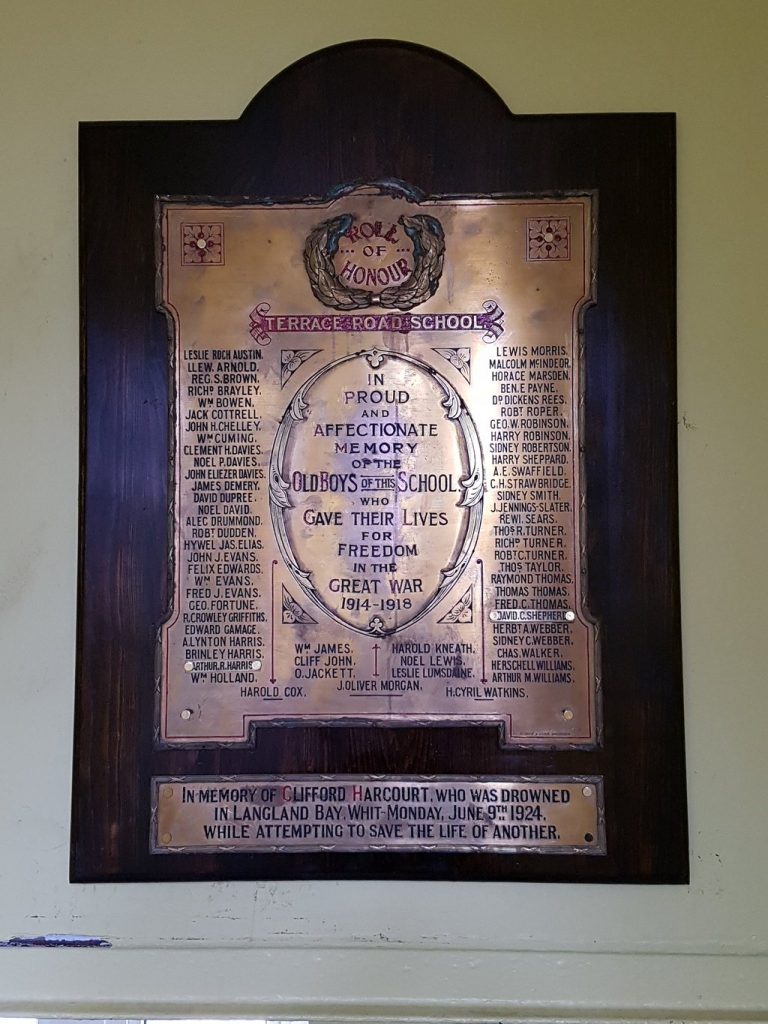

Another way of finding these connections is to look at one memorial and see how many of the men are listed on other local memorials. We have recently been given an image of the WW1 memorial in Terrace Road School, in the Mount Pleasant area of Swansea. This lists 65 men who ‘gave their lives for Freedom in the Great War, 1914-1918’.

Another way of finding these connections is to look at one memorial and see how many of the men are listed on other local memorials. We have recently been given an image of the WW1 memorial in Terrace Road School, in the Mount Pleasant area of Swansea. This lists 65 men who ‘gave their lives for Freedom in the Great War, 1914-1918’.

Many of these men appear on other local memorials in Swansea (as well as being listed  on the Swansea Cenotaph, which names all the local dead from WW1). One name that stands out is David Dupree – he is the subject of a previous blog post, and is named on the Hafod Isha works memorial.

on the Swansea Cenotaph, which names all the local dead from WW1). One name that stands out is David Dupree – he is the subject of a previous blog post, and is named on the Hafod Isha works memorial.

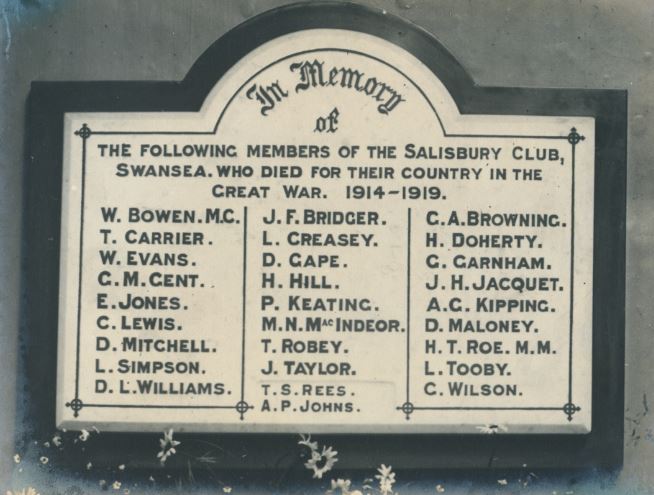

At least one of the men is named on the memorial in the Salisbury Club (which used to stand on Walter Road) – Malcolm McIndeor.

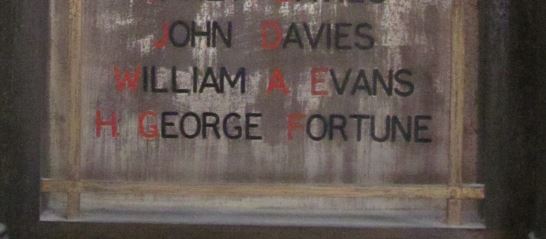

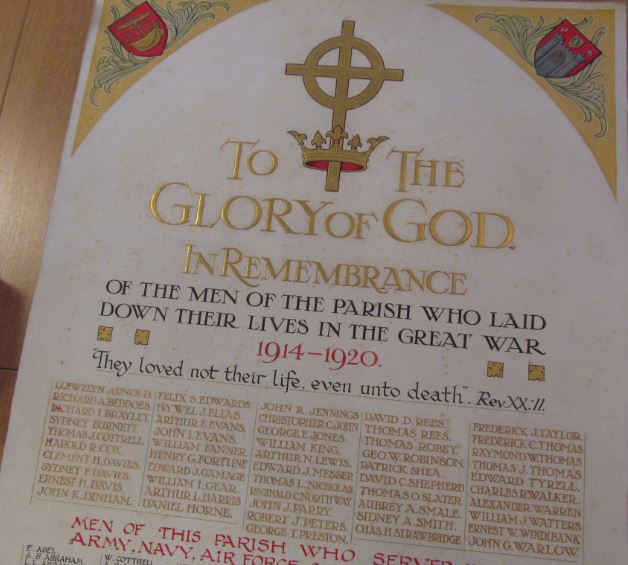

At least five of the men are named on the parish memorial of St Jude’s (a church which stood in Terrace Road) –

Llewelyn Arnold, Felix Edwards, Edward Gamage, Fred C. Thomas and George Fortune. The latter is also named on the memorial in Mount Pleasant Baptist chapel.

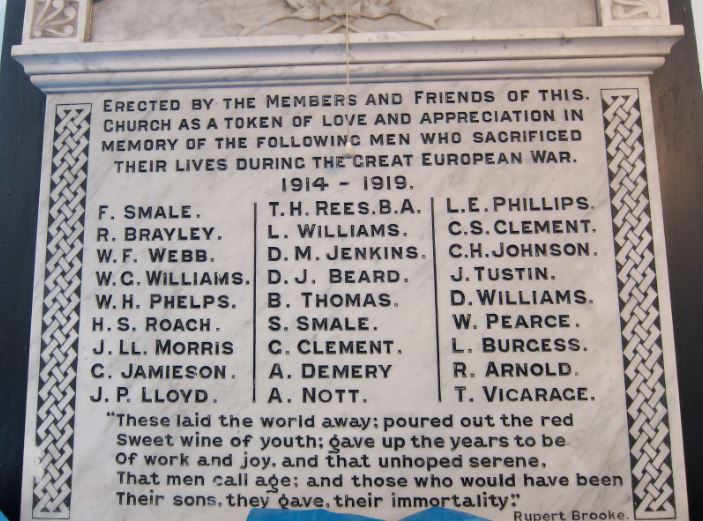

Richard Brayley is (almost certainly) the R. Brayley commemorated on Carmarthen Road chapel.

Further investigations will doubtless find more examples of these men listed on other local memorials.

g.h.matthews August 12th, 2017

Posted In: Uncategorized

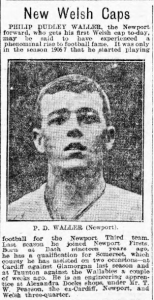

Philip Dudley Waller

Rodney Parade is now home to the Newport Gwent Dragons Rugby Club. The entrance gate, however, serves as a memory to the club’s past. It is dedicated to the 85 members of Newport Athletics Club who lost their lives during the First World War.

A large number of the names can be found in other local memorials around Newport – for example, 18 are commemorated on the memorial at St Mark’s Church, five on the Newport High School Old Boys’ memorial and three at Victoria Avenue Methodist Church. Many of these men served with ‘local’ regiments – at least 24 were with the Monmouthshire Regiment, and at least 18 were South Wales Borderers.

However, six of these men were killed while fighting as members of overseas forces – three with the Canadians, and one each with the Australian, New Zealand and South African forces. This of course indicates that they had emigrated before the outbreak of war. People emigrated for many different reasons at the turn of the twentieth century, but one of the most unusual cases must be that of Philip Dudley Waller.

Philip was born in Bath in 1889, but later moved with his parents to Llanelli, where he began his rugby career. He was a gifted forward, and played his first game for Wales at the tender age of nineteen. The Evening Express of 12 December 1908 (football edition, p.2) described his achievement as “a phenomenal rise to football fame” – he’d only started playing for Newport’s third team in the 1906-7 season. In 1910 Waller was selected to play for the British Lions on tour in South Africa. It appears that he and one of his team-mates had such a good time there that he decided to stay. An article in the Evening Express entitled “Great Loss to Newport Club” ( 31 August 1910, p.4, second edition) stated that “it is definitely reported that P.D. Waller and Melville Baker, of Newport, who are now with the British team, will remain in South Africa.”

Sadly, Phillip Waller died on active service in France on 14 December 1917. He was buried at Red Cross Corner Cemetery near Arras. The Llanelli Star wrote that he had “a wide circle of friends who regret his untimely though glorious death.” A few months later, the Cambria Daily Leader reported the death of a brother – “Richard Percy Waller, R.A.F., has been killed at Montrose. He had gained his wings as a pilot only a week before his death” (3 June 1918, p. 3). The War memorial in their home town of Llanelli does not list the names of the servicemen commemorated there, but the names of both brothers can be found on the Carmarthen County War Memorial Roll.He settled in Johannesburg, even becoming a member of the town council there. The Llanelli Star reported that he enlisted into the South African Heavy Artillery in August 1915 because he was “a good sport in every sense of the term and full of patriotic fervour, he saw it to be his duty to do something for his country” (5 January 1918, p.1). Indeed, the Llanelli Star was eager to sing Phil Waller’s praises generally: “Personally, he was a charming young man. Of fine physique, abundant fervour, and highly attractive manner, he was a very popular officer, loved by the men and regarded with very great favour by his supervisors.”

Meg Ryder June 16th, 2017

Posted In: Uncategorized

The Hafod Isha Memorial, Swansea

The ‘Welsh Memorials’ project is particularly interested in those war memorials that were established by particular communities to their men who were lost in the war. The most numerous of such memorials that we have collected come from chapels, but we are also interested in those that were created by schools, clubs and workplaces.

For workplace memorials there is the particular challenge that most of the places of employment in 1914 do not exist any more – for example, none of the 400 coal mines that were operative in south Wales in 1914 are still around, and in most cases their buildings have been razed. Similarly, most of the heavy industries of Wales have either closed down or relocated. However in what used to be one of the prime areas of the non-ferrous metals industry in Wales, you can still see the building that once housed the Hafod Isha works, where nickel and cobalt was smelted.

For workplace memorials there is the particular challenge that most of the places of employment in 1914 do not exist any more – for example, none of the 400 coal mines that were operative in south Wales in 1914 are still around, and in most cases their buildings have been razed. Similarly, most of the heavy industries of Wales have either closed down or relocated. However in what used to be one of the prime areas of the non-ferrous metals industry in Wales, you can still see the building that once housed the Hafod Isha works, where nickel and cobalt was smelted.

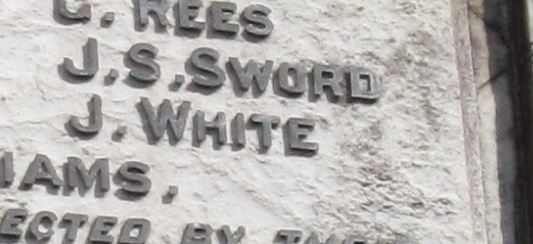

On the outside of the building is a stone monument, listing the names of eleven men killed in the war. Interestingly, the memorial states it was instigated by the men’s ‘fellow employees’, rather than by the company itself.

Using items from the Swansea newspapers, it is possible to find out more about most of these men.  One of them has already been the subject of a blog article – Dai Dupree.

One of them has already been the subject of a blog article – Dai Dupree.

The first set of clues come in two ‘Rolls of Honour’ in the Cambria Daily Leader, which list the men from the works that had enlisted in September and October 1914. There are 64 names in the list published on 23 October – and of these, seven (Dupree; George; Isaac; Jenkins; Rees; Sword and Williams) are on the memorial.

Thus we know that E. S. George is Emin Stanley George, killed in the vicinity of Ypres while serving with the Dorsetshire Regiment in March 1915; George Rees was killed in June 1915 while serving with the South Wales Borderers; William Edward Isaac was serving in the Machine Gun section of the Welsh Regiment when he was killed in August 1916 and Fred Jenkins was in the Oxford and Bucks Regiment when he was killed in the same month on the Salonican Front. The fact that Charles Williams is identified in the October 1914 list as serving with the ‘South Lancashire Light Infantry’ makes it possible to say with some certainty that the ‘C. Williams’ on the Hafod Isha memorial is the Charles Thomas Williams who was killed on the Salonica Front in September 1918 while serving with the South Lancashire Regiment.

Perhaps the youngest of these men was Harold Grey, who died aboard S.S. Dundalk six days before his nineteenth birthday, on 14 October 1918.

Other newspaper reports make it easy to identify some of the other men. A brief notice of the death of Maurice Kirwan, who was killed in action in France in August 1917, aged 20, noted that ‘he was formerly employed at the Hafod Isha works’. This information was also given in the obituary to George Pickett , who died aboard H.M.S. Arbutus, which was torpedoed by a German U-boat in December 1917.

The two that cannot be identified on the list of fallen complied by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission are J. White, for whom there are too many possibilities to be certain, and J. S. Sword, whose inclusion needs some further research. James Spence Sword is listed in the October 1914 list in the Cambria Daily Leader: records show that he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 13 October 1914 and served on various warships up until his discharge in early 1919. Despite the fact that his name is missing in the CWGC list, the fact that his work colleagues considered him a casualty of the war suggests that he died later as a result of a wound or illness picked up during his war service.

The two that cannot be identified on the list of fallen complied by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission are J. White, for whom there are too many possibilities to be certain, and J. S. Sword, whose inclusion needs some further research. James Spence Sword is listed in the October 1914 list in the Cambria Daily Leader: records show that he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 13 October 1914 and served on various warships up until his discharge in early 1919. Despite the fact that his name is missing in the CWGC list, the fact that his work colleagues considered him a casualty of the war suggests that he died later as a result of a wound or illness picked up during his war service.

One further question that cannot be easily answered is why some other war casualties who were noted in the newspapers as former employees of Hafod Isha were not included on the memorial. One example of this is James Heffron, whose death while serving with the Somerset Light Infantry was reported in August 1915.

g.h.matthews February 27th, 2017

Posted In: Uncategorized

Joining the Dots

Individuals belong to several communities at once, and have loyalties and relationships at many different levels. This was true – and perhaps more so – a hundred years ago. A young man who went off to war in 1914-18 might have his presence missed in different ways by the communities of which he was part – besides, clearly, the impact upon his immediate family.

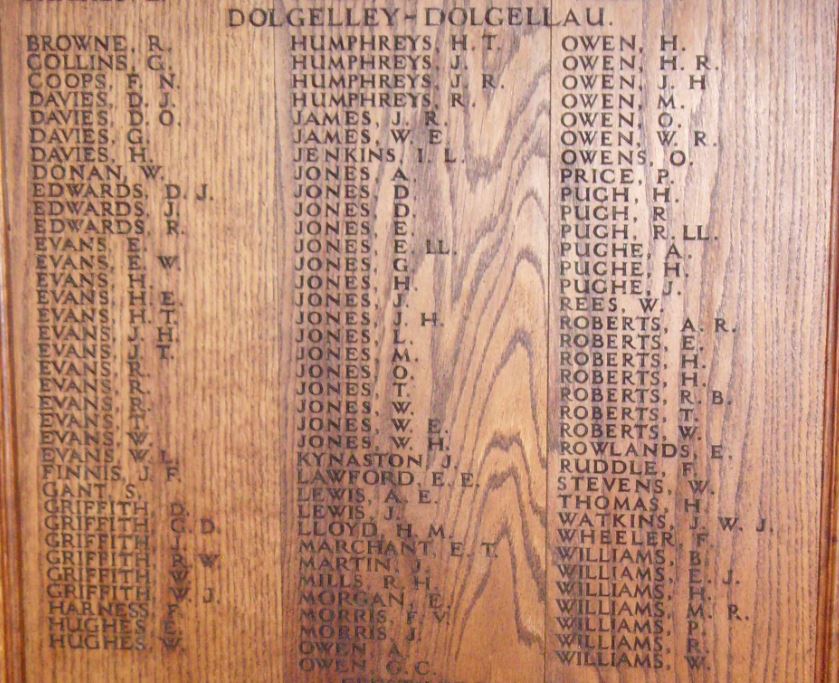

Thus individual soldiers and sailors can be commemorated on more than one memorial. In fact, most of the Welshmen who fell in the war will have their names remembered on at least two memorials. To give one example that has been considered in an earlier blog post, the 11 men from the Rhydymain area who were killed in the First World War were commemorated on memorials in two chapels, and all bar one of them are named on the Dolgellau memorial.  In addition; the fallen from north Wales are also named on the ‘Memorial Arch’ in Bangor; all dead Welsh servicemen should be named in the ‘Welsh National Book of Remembrance’; all British casualties should be found in the volume ‘Soldiers Died the Great War’; and all the Commonwealth dead are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC).

In addition; the fallen from north Wales are also named on the ‘Memorial Arch’ in Bangor; all dead Welsh servicemen should be named in the ‘Welsh National Book of Remembrance’; all British casualties should be found in the volume ‘Soldiers Died the Great War’; and all the Commonwealth dead are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC).

Of course, given that so many Welshmen had common surnames, it is not always possible to be certain whether the Jones, Williams or Evans commemorated refer to the same individuals.

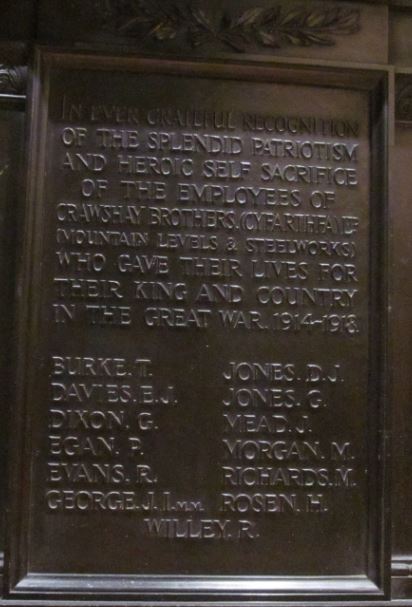

When the serviceman had a less common surname, the job can be easier.  Harry Rosen is commemorated on both the memorial of his place of worship – the synagogue in Merthyr Tydfil – and in his workplace – the Crawshay Brothers Mountain Levels and Steelworks. (Both of these magnificent memorials are now held at the Cyfarthfa Castle Museum). There are only two ‘H. Rosen’s listed on the CWGC database, and it is clear that the Merthyr Rosen served with the Royal Naval Division and was killed on the final day of 1917.

Harry Rosen is commemorated on both the memorial of his place of worship – the synagogue in Merthyr Tydfil – and in his workplace – the Crawshay Brothers Mountain Levels and Steelworks. (Both of these magnificent memorials are now held at the Cyfarthfa Castle Museum). There are only two ‘H. Rosen’s listed on the CWGC database, and it is clear that the Merthyr Rosen served with the Royal Naval Division and was killed on the final day of 1917.

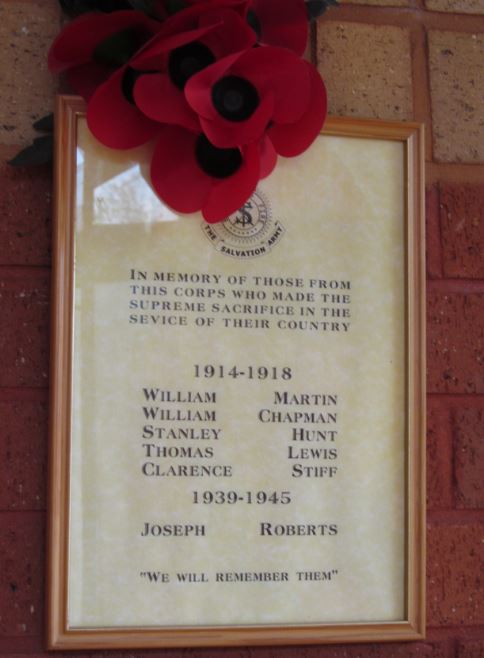

Another young Welshmen with a name that can easily be traced was Clarence Stiff of Cwmbran. Family-held material on his tragic story was shared with the ‘Welsh Voices of the Great War’ project in 2010.  He was just seventeen years old when he was killed on the Western Front in 1915. His obituary in a local newspaper calls him a ‘fine youth’: ‘He was an enthusiastic cricketer, and a member of the Cwmbran Cricket Club. He was also a scholar at the Cwmbran Wesleyan Sunday School.’

He was just seventeen years old when he was killed on the Western Front in 1915. His obituary in a local newspaper calls him a ‘fine youth’: ‘He was an enthusiastic cricketer, and a member of the Cwmbran Cricket Club. He was also a scholar at the Cwmbran Wesleyan Sunday School.’

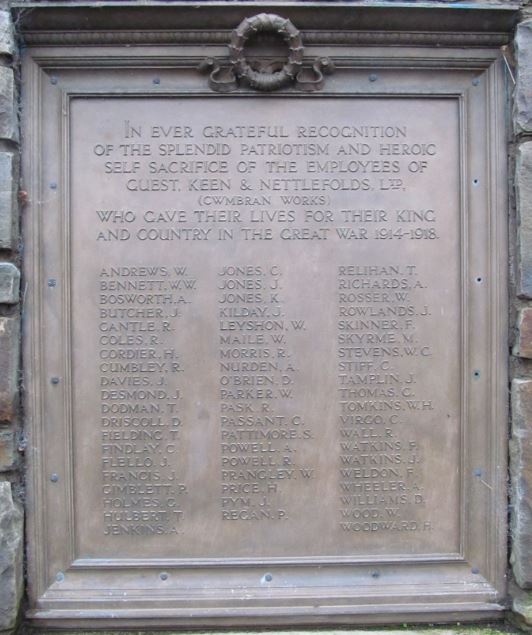

Clarence is commemorated on three different memorials in Cwmbran. Wooden boards in St Gabriel’s Church list the names of 86 men of the parish who were killed, including Clarence. His name is also among the five WW1 casualties commemorated in the Salvation Army Hall on Wesley Street. Also, he is commemorated by his employers, the Cwmbran works of the Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds Company (who, as explored in a previous blog post, created memorials in their numerous workplaces around South Wales).

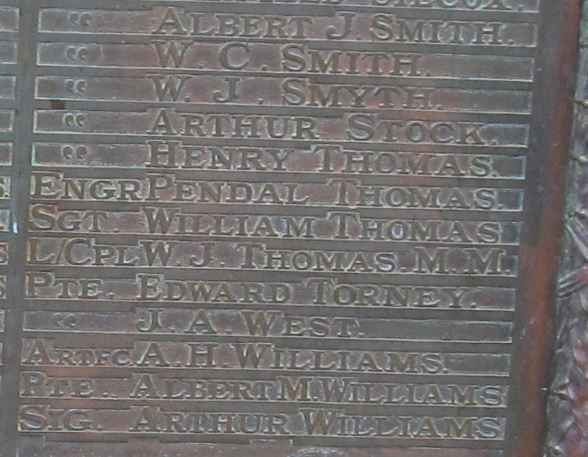

Sometimes an unusual first name is enough to be able to make a connection. There is a Pendal Thomas, engineer, named on Pontardawe’s WW1 memorial. There is an R Pendal Thomas named on the memorial at Cardiff’s Pembroke Terrace Calvinistic Methodist chapel (now converted to be a restaurant). There is no Pendal Thomas listed on the CWGC database, but there is a Robert Pendrill Thomas, third engineer, who died on board S.S. Bayronto on 30 July 1918. The database notes that his parents were Hannah and Robert Thomas of Pontardawe. Thus there is no doubt that the same man is commemorated on the Pontardawe and Cardiff memorials.

g.h.matthews January 19th, 2017

Posted In: Uncategorized

Stained glass windows in Welsh churches as WW1 memorials

There is, of course, a long tradition within the Christian religion of incorporating stained glass windows in churches which relate stories from the Bible, or of saints’ lives. There are a wealth of notable examples in churches in north Wales of windows created in the medieval or early modern period. In the Victorian period, when many ancient churches were refurbished, stained glass windows were installed in churches all over Wales.  As well as Biblical scenes, some of these images were in honour of notable benefactors. There are also examples in Welsh churches of stained glass windows as memorials to the Boer War, such as this example from St Mary’s, Monmouth.

As well as Biblical scenes, some of these images were in honour of notable benefactors. There are also examples in Welsh churches of stained glass windows as memorials to the Boer War, such as this example from St Mary’s, Monmouth.

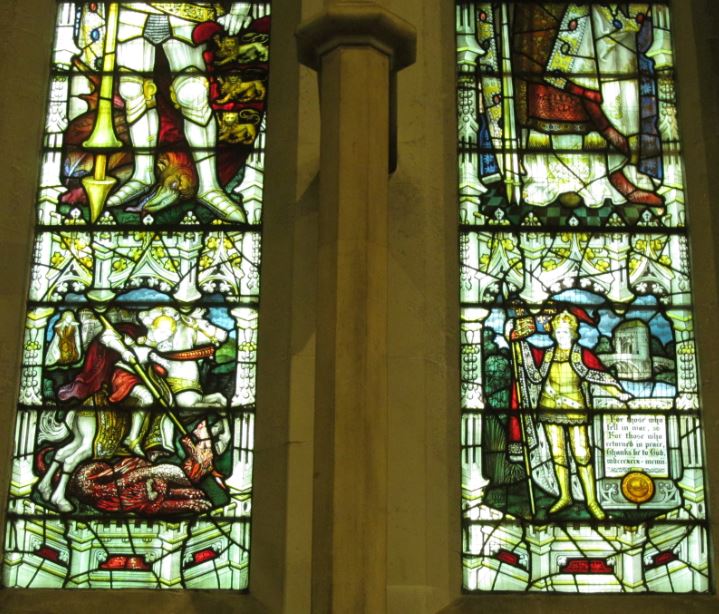

Thus it is not too surprising that stained glass windows in churches became a way of commemorating those who served in the First World War, and in particular those who were lost. However, it is remarkable how many such memorials were established in Wales. Martin Crampin’s excellent book, Stained Glass from Welsh Churches (published by Y Lolfa in 2014) contains thirty pages of photographs of these WW1 memorials.

Although a fair number of stained glass windows were established in Nonconformist chapels, the majority of these WW1 memorials are in Anglican churches. The imagery they contain is often very vivid and thought-provoking. Many contain images of First World War soldiers – one particularly striking example is to be seen in Christ Church, Rossett, in the north-eastern corner of Wales.

Dedicated in 1925 to ‘the men of the parish who gave up their lives in the Great War’, this pictures three soldiers: on the right-hand side, a wounded soldier of the Welsh Regiment receives succour from a stretcher-bearer of the RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps).

For further images of this, visit the web-pages created by Martin Crampin on ‘Stained Glass in Wales’.

Several images on the ‘Stained Glass in Wales’ website show windows that contain both First World War soldiers and Christ, making the explicit connection between the suffering of the contemporary soldiers and the story of Christ on the cross. Thus the Church of St Pedrog, Llanbedrog (from 1918) shows ‘A fallen soldier with Christ and angels’ and St Mary’s Spittal (Pembrokeshire, from 1916) shows ‘The Risen Christ meeting the fallen soldier’.

In the Church of St James, Manorbier, there is a collection of service personnel in a montage with Christ on the cross, including a nurse.

One example not in the online database is the memorial window in Llanfrechfa, near Cwmbrân. This shows the risen Christ with a fallen soldier, and is a memorial to Major Edmund Styant Williams who was killed at Ypres on 8 May 1915.

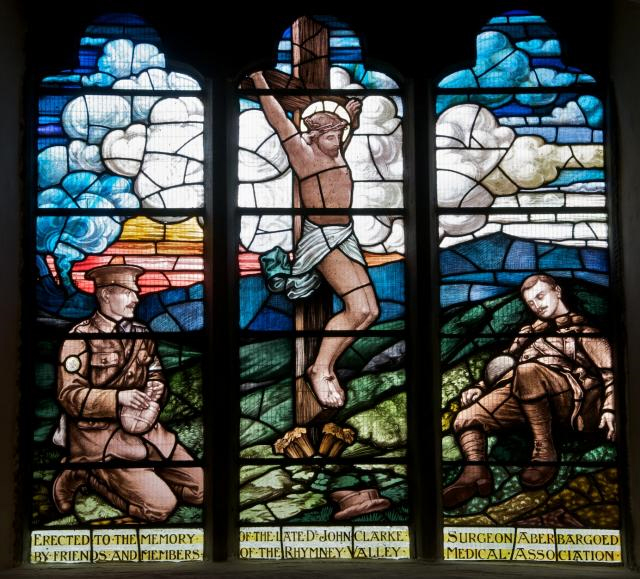

It is also poignant to note when some of these memorials were unveiled. Some were created in the 1920s; some in 1919, in the immediate aftermath of war; some while the war was still being fought. One striking example, in the church of St Sannan, Bedwellty, was dedicated on Christmas Eve, 1916.

This shows Christ on the cross with soldiers in WW1 uniform at the scene: one kneeling; one lying wounded or dead. (Further information on this can be found in an article by David Mills in the Journal of the Gelligaer Historical Society vol.23 – Great War edition 2, 2016).

The window is dedicated to a local surgeon, Dr John Clarke, and the kneeling figure on the left bears a distinct resemblance to him. Similarly, the wounded soldier looks like another local man who fell, Sgt. W. J. Haskoll of the First Monmouthshire Regiment, who died, aged 31, in France on 25 May 1915.

g.h.matthews December 21st, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

The ‘Dead Man’s Penny’: A family’s tribute to a fallen son

At Boncath near Cardigan, two years following the end of hostilities in November 1918, a memorial obelisk was erected in the grounds of Vachendre Chapel in memory of Private Tom Lewis, who died on 27 September 1918 while a Prisoner of War. He was twenty-seven years old and was the son of Jonathan and Martha Lewis of Winllan, Boncath. He was also the only member of the chapel to perish in the Great War. Tom Lewis is not buried at Vachendre Chapel; to view his actual resting place you need to travel to the Department of the Nord in France, as this fallen soldier of Boncath is buried at Glageon Communal Extension Cemetery, near the village of Trelon, just a few kilometres from the Belgian border. At the time he was serving with the 1st Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment.

The type of obelisk on display at Vachendre Chapel, in memory of Tom Lewis, is not particularly remarkable; such imagery or memorial type was frequently adopted for funerary purposes in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and even today remains a common sight at cemeteries throughout west Wales and beyond. What is different, in this case, is the presence of a large coin embedded into the boundary footings of the memorial. This is in fact the memorial medallion issued to Tom Lewis’s family, and to all the families of fallen men and women following the Great War, from a grateful ‘King and Country’.

The type of obelisk on display at Vachendre Chapel, in memory of Tom Lewis, is not particularly remarkable; such imagery or memorial type was frequently adopted for funerary purposes in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and even today remains a common sight at cemeteries throughout west Wales and beyond. What is different, in this case, is the presence of a large coin embedded into the boundary footings of the memorial. This is in fact the memorial medallion issued to Tom Lewis’s family, and to all the families of fallen men and women following the Great War, from a grateful ‘King and Country’.

The presence of this soldier’s memorial medallion is an unusual feature for a First World War memorial site. More popularly known as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ (some would suggest disparagingly), over a million of these bronze medallions were produced in the immediate post-war years.  The medallion measured 120mm in diameter and was designed by the sculptor Edward Carter Preston. The name of the fallen serviceman is given, but the rank of the individual is not, reflecting equality in death, if not in life. The figure of Brittania, complete with trident, dominates the allegory, together with the image of a lion, and two dolphins, the latter representing British sea power. At the base, another lion is seen devouring a German eagle. ‘He died for freedom and honour’ is inscribed around the edge (of course replaced by ‘she died …’ in the case of women service personnel who perished). Although at the time some viewed the medallion as a wholly inadequate form of recognition for those who had paid with their lives, it is clear that the family of Tom Lewis viewed it with great pride, giving it a prominent place at their son’s memorial site.

The medallion measured 120mm in diameter and was designed by the sculptor Edward Carter Preston. The name of the fallen serviceman is given, but the rank of the individual is not, reflecting equality in death, if not in life. The figure of Brittania, complete with trident, dominates the allegory, together with the image of a lion, and two dolphins, the latter representing British sea power. At the base, another lion is seen devouring a German eagle. ‘He died for freedom and honour’ is inscribed around the edge (of course replaced by ‘she died …’ in the case of women service personnel who perished). Although at the time some viewed the medallion as a wholly inadequate form of recognition for those who had paid with their lives, it is clear that the family of Tom Lewis viewed it with great pride, giving it a prominent place at their son’s memorial site.

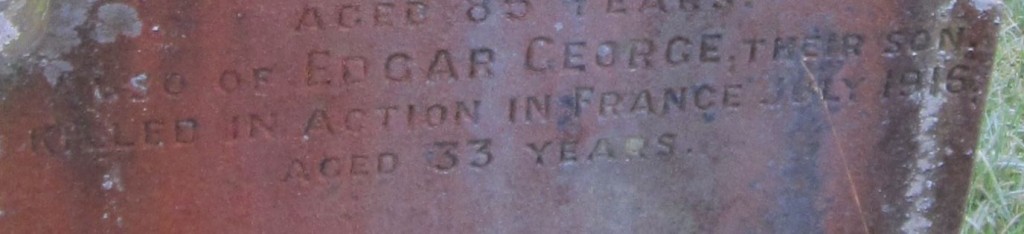

As with the obelisk at Vachendre Chapel, many chapel, church, and war memorial sites, which held the names, if not the mortal remains of the fallen, were given prominence and significance by the families and close friends of the fallen. The names of servicemen, buried or lost abroad, remain a common feature on family gravestones throughout Britain. Here is an example from Anglesey: the grave of William Jones Owen, who died in the Battle of Mametz Wood (July 1916).

These sites acted as a form of surrogate grave for those who could not afford to make the trip out to France or Belgium, or whose loved ones had no known resting place, or who had perished at sea, or were laid to rest in more distant lands such as Mesopotamia, Palestine, Gallipoli, or Salonika. During the immediate post war years such sites were visited regularly by relatives and close friends; a constant reminder to those living in the immediate vicinity of the sacrifices made by the fallen, and indeed the suffering of those left behind. Today, most of these sites, and the tributes they hold, go unnoticed, but each is a material reminder of sacrifices made and heartache endured by those closest to the fallen.

The Vachendre obelisk is significant for one other reason. At the unveiling in October 1920, local veterans, who were there in force, marched from the village of Boncath to the chapel ground to witness the speeches that accompanied the unveiling. Two contrasting opinions on the war were evident in these addresses. Fortunately for the historian the speeches were reported in the Cardigan and Tivyside Advertiser, on 22 October 1920. The Reverend Esgar James of Cardigan put forward a distinctly anti-militarist theme in his address, stating, ‘they were not there to glorify militarism nor war, but to pay tribute to one who had laid down his life for them’. The unveiling itself was performed by Colonel Spence Colby who, in no uncertain terms, gave a different view of events, stating, ‘those miserable people who went up and down the country speaking against what they were pleased to call militarism, should leave the country, and show themselves to be what they really are – traitors to their country’. It is difficult to judge from this short newspaper report whether the Colonel was responding directly to Esgar James’s comments, or that he was targeting members of the Nonconformist community when referring to ‘those miserable people’, but his contrasting views, expressed with obvious animosity and vitriol, may be seen as indicative of tensions over the conduct of the war between some Nonconformist elements and those fully behind Britain’s part in the conflict, such as Colonel Spence Colby. The degree to which anti-war sentiments pervaded Welsh rural society throughout 1914-1918 and beyond remains a contentious issue among historians of the Great War in Wales, particularly around the part played by Nonconformist ministers in spreading anti-war rhetoric and pacifist beliefs. It is perhaps unwise to make general judgements about attitudes towards the war in this part of Wales based upon one newspaper report and one memorial unveiling, but this source can form part of a wider study of memorial unveiling speeches in the 1920s, many of which were covered, verbatim, in local newspapers. These points aside, the views of the Reverend James tend to fit the image of the radical, anti-war Nonconformist minister in Wales, put forward by some historians, and even expresses a general attitude that, some believe, was widespread in Britain during the post-war era – more cynical and certainly more disillusioned by the war and its consequences.

Dr Lester Mason, University of Wales Trinity St David

To get to the Vachendre Chapel site, travel on the A484 Tenby-to-Cardigan road, and a mile and half north of Crymych (after passing through the village of Blaenffos) take a right onto the B4332 for Cenarth/Newcastle Emlyn. At Boncath village take the right turn to Bwlch y Groes . One mile down this road on the right-hand side is the Chapel.

g.h.matthews October 24th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Dai Dupree

“Thus the close of a life which had radiated joy into many a Swansea home”

David Arthur ‘Dai’ Dupree/Du Pree (spellings vary) was evidently a remarkably popular young man. He was a keen rugby footballer, an enthusiastic member of Sunday school and, as the Herald of Wales noted, one of those people ‘so favoured by fortune that when they cross our lives it seems as though a warm beam of sunshine is playing upon us.’

He was born in Swansea around 1895. At the time of the 1911 census he was living with his parents and five siblings at 12 Short Street, not far from Swansea’s High Street station.

He was born in Swansea around 1895. At the time of the 1911 census he was living with his parents and five siblings at 12 Short Street, not far from Swansea’s High Street station.

The census says that he was working as a railway messenger, whilst his two older brothers, William and Frederick, worked as railway shunters. However, Dai must have changed employment as he is listed with ten other men on the Hafod Isha Works memorial on Morfa Road.

Clearly keen to do his bit for the country, Dai was among the first recruits to enlist in Swansea. The Cambria Daily Leader reported on 7 September 1914 that ‘the 3.35 train to London on Monday afternoon carried a large batch of recruits to Cardiff and London,’ under the headline A GREAT SEND OFF. Dai Dupree and one other recruit (Will Harris, Trafalgar Terrace), were picked out for special attention among this batch. Dai was described as ‘a popular young footballer who had friends in countless camps at Swansea,’ whilst Will was ‘another young footballer with hosts of friends.’

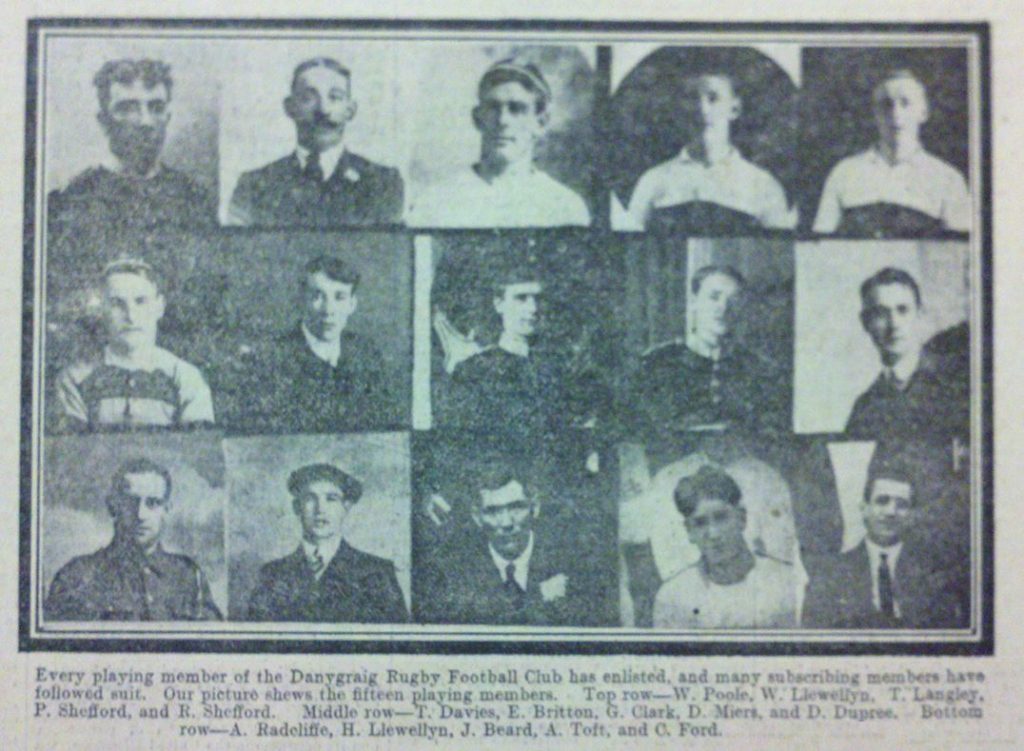

A newspaper from later that month carried a photograph of all of the players of the Danygraig rugby team, every one of whom had volunteered for the war: Dai is on the right of the middle row.

There are many column inches dedicated to Dai in both the Cambria Daily Leader and the Herald of Wales. Before the war he turned up frequently in the sports pages: as well as playing rugby for Danygraig he played soccer for the Alexander Corinthians (attached to the Sunday school he attended).  During the war, he was one of the performers at a Welsh Guards’ Concert. The article in the Cambria Daily Leader quotes extensively from an unnamed soldier who was at the event, and had a splendid time. Dupree was on after the Welsh Guard Glee Party, whose ‘renderings of “Aberystwyth” and “Ton-y-Botel” raised the audience to a high stage of emotionalism, and the English folk present must have thought that we truly were a strange people.’ A hard act to follow then! Frustratingly, the only thing written about Dai’s act is that “the comedians were great, and Private Dupree should in future be known as “the old man from Abertawe.” It would have been interesting to know what Dai’s performance was like, and how he earned such a nickname. Later, the Herald of Wales said that a song he created called “the Spanish Onion” was ‘illustrated by eccentric actions, [and] used to reduce us to helpless fits of laughter. They had heard him in it at the front, with like results.’ Once again, however, the newspaper’s information is disappointingly sparse when it comes to details about his antics.

During the war, he was one of the performers at a Welsh Guards’ Concert. The article in the Cambria Daily Leader quotes extensively from an unnamed soldier who was at the event, and had a splendid time. Dupree was on after the Welsh Guard Glee Party, whose ‘renderings of “Aberystwyth” and “Ton-y-Botel” raised the audience to a high stage of emotionalism, and the English folk present must have thought that we truly were a strange people.’ A hard act to follow then! Frustratingly, the only thing written about Dai’s act is that “the comedians were great, and Private Dupree should in future be known as “the old man from Abertawe.” It would have been interesting to know what Dai’s performance was like, and how he earned such a nickname. Later, the Herald of Wales said that a song he created called “the Spanish Onion” was ‘illustrated by eccentric actions, [and] used to reduce us to helpless fits of laughter. They had heard him in it at the front, with like results.’ Once again, however, the newspaper’s information is disappointingly sparse when it comes to details about his antics.

Dai Dupree died on 27 September 1916, aged 22. He was fondly remembered both in Swansea and amongst his comrades in the Welsh Guards. Unusually, his chapel dedicated a memorial to him alone, rather than having a memorial dedicated to all who lost their lives in the war. This may have been because his memorial was unveiled whilst the war was still in progress. The Cambria Daily Leader reported on 20 November 1916 that ‘at Alexandra-road Chapel, Swansea, a brass tablet, recording the names of members on active service, and another in memory of Corpl. David Dupree, of the Welsh Guards, was unveiled.’ Sadly, Alexander-road Chapel has now closed, and, as is the case with thousands of other closed chapels across Wales, we do not know the fate of either memorial.

Like many other Welsh soldiers, Dai was an ordinary young man, praised as funny, kind and ‘had he been spared, would have been a leader in a wider sphere.’ In the words of the Herald of Wales: ‘There are some lads so favoured by fortune that when they cross our lives it seems as though a warm beam of sunshine is playing upon us. David Dupree was all sunshine.’

g.h.matthews July 29th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Memorials in a small rural village

As the ‘Welsh Memorials’ project gathers information of WW1 memorials from all over Wales, one pattern that it to be expected is that memorials in sparsely populated rural parts of Wales are generally less substantial that memorials from urban areas. It stands to reason that chapels and churches in these parts would not have provided as many men for the armed forces as those in more densely populated areas. Furthermore, in industrial Wales there were often memorials established by workplaces, which sometimes list dozens of names of the fallen. Clearly this is not going to be the case in areas where the men worked as tenant farmers or farm labourers.

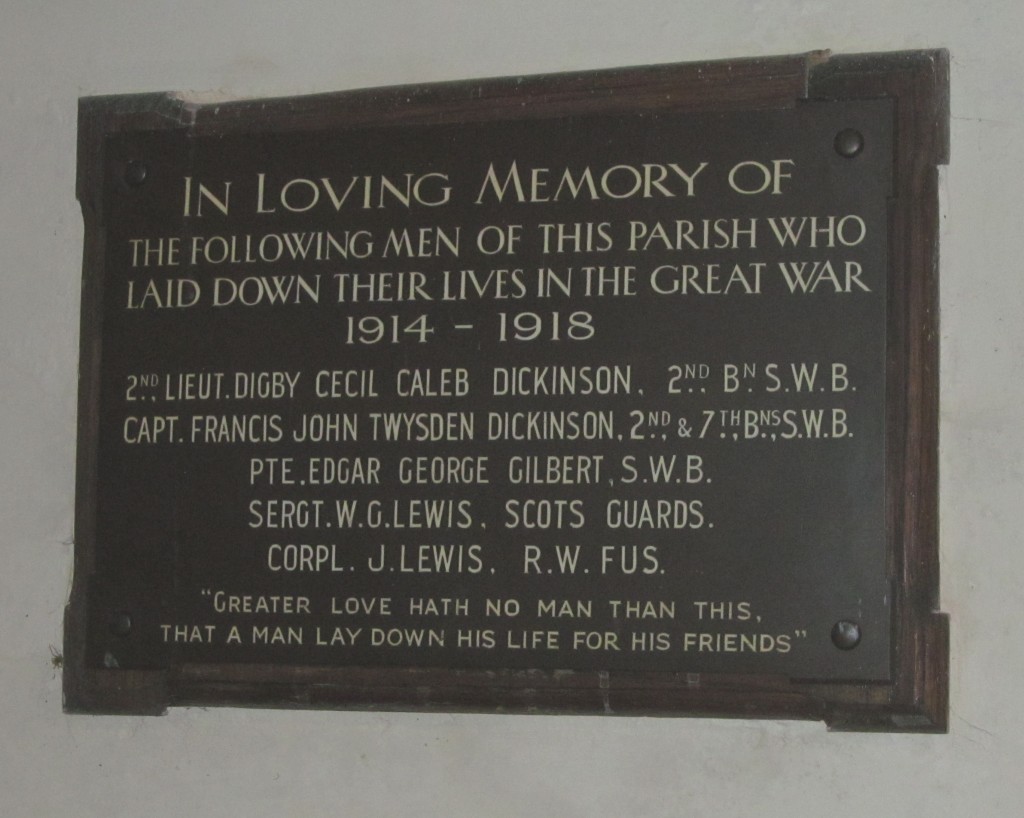

So the memorial in the ancient church at Aberyscir, four miles west of Brecon, is rather typical of the modest commemorations in rural Welsh churches. It contains details of five men of the parish, arranged in alphabetical order.

The first two names on the list are brothers, sons of Francis and Lucy Dickinson of Aberyskir Court, from a local gentry family. Both died in the final months of the war. The younger brother, Digby Dickinson died on the Western Front on 18 August 1918, leading his men in an attack. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission gives his date of death as 28 August, but this report in the local newspaper, which gives a glowing account of the young lieutenant’s courage, confirms that it was actually the 18th.

The elder brother, Francis Dickinson,

The elder brother, Francis Dickinson, died a month later in the battle of Doiran on the Salonica Front. This battle, in a forgotten theatre of the war, was a complete failure for the British, and cost the lives of dozens of South Wales Borderers.

died a month later in the battle of Doiran on the Salonica Front. This battle, in a forgotten theatre of the war, was a complete failure for the British, and cost the lives of dozens of South Wales Borderers.

A memorial service for the brothers was held in Brecon on 1 November 1918, ten days before the Armistice brought the fighting to a close.  This service was held two days after the death of another of the men commemorated on the tablet.

This service was held two days after the death of another of the men commemorated on the tablet.

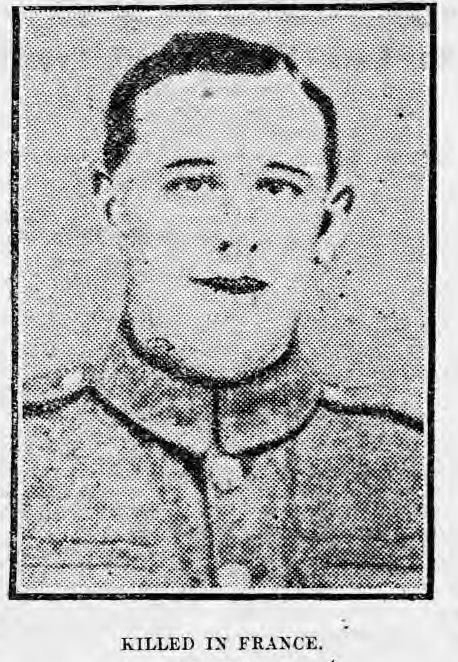

John Lewis, son of John and Anne Lewis of Llanddew, was killed on the Western Front on 29 October 1918. His photograph can be found here on the Cymru1914 website.

No information has yet been found regarding the other Lewis named on the Aberyscir memorial, Sgt. W. G. Lewis. However, there are many details regarding Edgar Gilbert. He was the son of Eli and Elizabeth Gilbert of Llwyn-llwyd, Aberyscir. Prior to the war he had been working as a collier in Llanhilleth. Both he and his brother Joseph joined the South Wales Borderers in the summer of 1915.

Edgar was wounded in early 1916 (see an extract from a letter here) but returned to action. On 25 July 1916 he was wounded severely in the kidneys, and as a friend went to rescue him and carry him to safety both were killed by machine gun fire. The news was conveyed back to the family by his brother Joseph.

Edgar Gilbert is commemorated on the Thiepval memorial as he has no known grave – along with over 72,000 other names of British and Commonwealth soldiers who died in the Somme area. However, his name does appear on another memorial – his parents’ gravestone in the churchyard at Aberyscir.

g.h.matthews July 22nd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

The Battle of Armageddon

As the work of collecting details of a large number of Welsh war memorials continues, one aspect that we can study is what the people at the time called the conflict we now know as ‘World War One’. This can give us an indication of how they understood the war at the time.

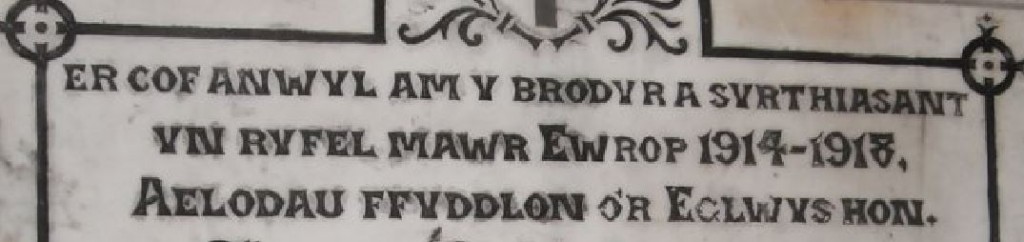

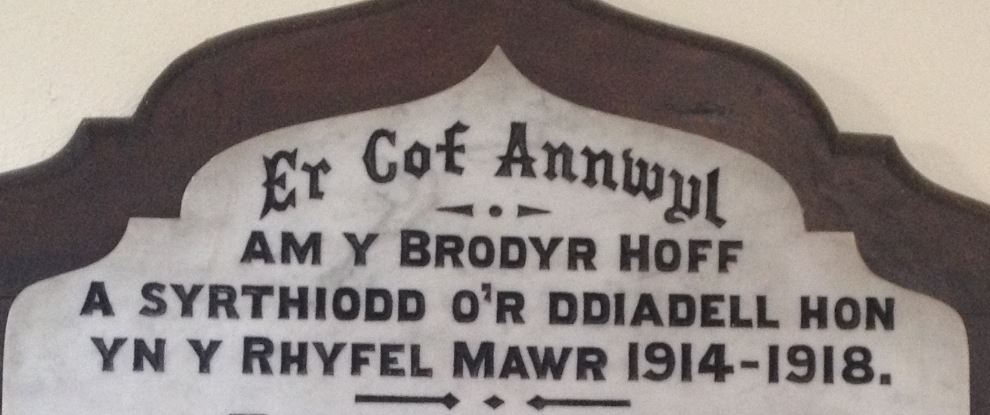

The most common name is ‘The Great War’ in English / ‘Y Rhyfel Mawr’ in Welsh. This is particularly true of those memorials that were commissioned in the years after the war. See, for example, the memorial in Moriah, Ynystawe.

A minor variation is seen in some memorials which refer to ‘the Great European War’ (such as the memorials of Conway Road Methodist church, Cardiff, Noddfa, Abersychan, or Carmarthen Road, Swansea (below). Similarly, the memorial in Hermon, Pembrey, refers to ‘Ryfel Mawr Ewrop’.

When dates of the conflict are given, the tendency is to note ‘1914 – 1918’, although some, such as the memorials in Bethel, Sketty or Mount Pleasant, Swansea, give ‘1914 – 1919’ (which reflects that fact that it was just an Armistice in November 1918, with the Peace Treaty being signed the following year).

In some chapel memorials, however, there are alternative names given to the conflict. The Roll of Honour in the Tabernacl, Morriston, refers in Welsh to ‘Rhyfel Rhyddid’ (‘The War of Freedom’), and in English, ‘the Great War, 1914-18, for Liberty and Justice’. It is worth pausing to reflect upon this declaration: it reminds us that people at the time could come to the conclusion that this was a war for fundamental principles, and thus a just war.

In some chapel memorials, however, there are alternative names given to the conflict. The Roll of Honour in the Tabernacl, Morriston, refers in Welsh to ‘Rhyfel Rhyddid’ (‘The War of Freedom’), and in English, ‘the Great War, 1914-18, for Liberty and Justice’. It is worth pausing to reflect upon this declaration: it reminds us that people at the time could come to the conclusion that this was a war for fundamental principles, and thus a just war.

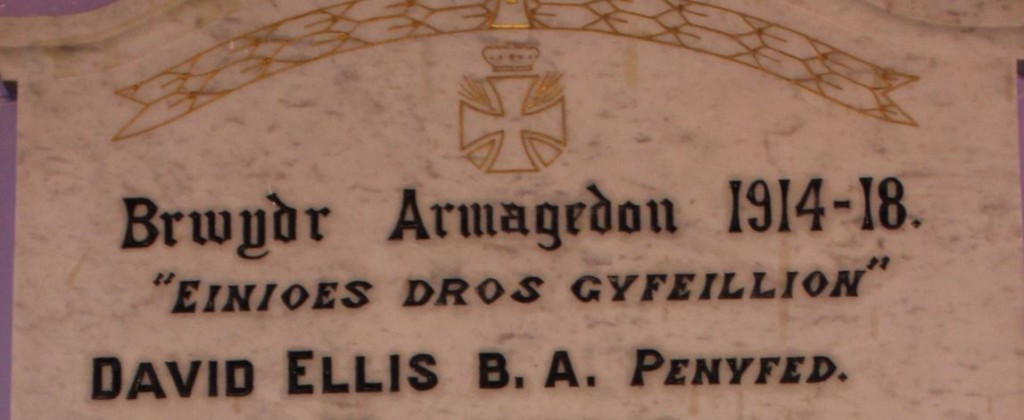

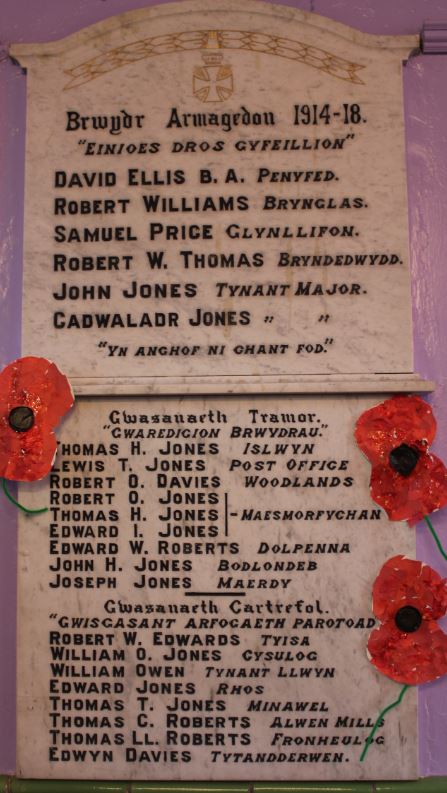

There is another label given to the war in the Methodist chapel in Dinmael, in Uwchaled, Conwy county borough: ‘Brwydr Armagedon 1914-18’ – ‘The Battle of Armageddon 1914-18’.

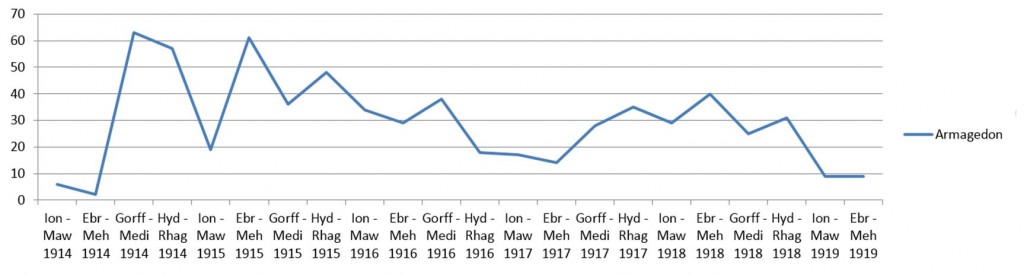

So far, this is the only memorial that has come to light which refers to ‘Armageddon’, but it reflects how people were referring to the war at the time. It is possible to trace the use of the word ‘Armageddon’ (‘Armagedon’ in Welsh) in the Welsh newspapers of the war years by using the tremendous online collection organised by the National Library of Wales. There is some discussion of this in my forthcoming volume Creithiau, which will be published by the University of Wales Press in August. However, the graph below did not make it into the final version:

Frequency of appearance of the word ‘Armagedon’ in the Welsh Newspapers Online collection, 1914 i 1918, by three-monthly periods

It is clear from this that there were only a few references to ‘Armagedon’ in the months before the start of the conflict, but many instances during the months of the war, with peaks in the first months, and during the Second Battle of Ypres, the Battle of the Somme and the bloody final months in 1918.

Thus, as they looked back upon the catastrophic four and a half years, it was natural for the chapel-goers of Dinmael to use Biblical language, and to compare the conflict to the battle described in the Book of Revelation as the cataclysm at the end of the world.

Two more aspects of this memorial to note: first, look at the extraordinarily high proportion of men with the surname Jones – 12 out of 23. It is not surprising that this memorial (like many others in rural Wales) gives the farm name as well, to differentiate between the men with similar names.

Two more aspects of this memorial to note: first, look at the extraordinarily high proportion of men with the surname Jones – 12 out of 23. It is not surprising that this memorial (like many others in rural Wales) gives the farm name as well, to differentiate between the men with similar names.

Secondly, note the first name on the list: David Ellis, B.A., Penyfed. This is the poet David Ellis, referred to as ‘y bardd a gollwyd’ – ‘the poet that was lost’, who served with the Welsh unit of the RAMC. See, for example one of his poems here and one of his letters here. He disappeared while serving in Salonica in June 1918.

g.h.matthews June 27th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized